New study helps scientists better understand the world of walruses

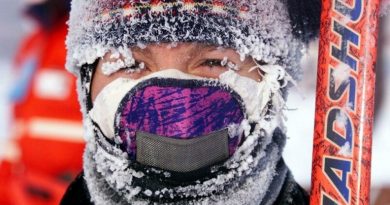

(Loren Holmes / Alaska Dispatch)

There is a magical spot in the northern Bering Sea where, if ice and weather conditions are just right, large concentrations of Pacific walruses seem to be able to enjoy a smorgasbord of their favorite foods while finding convenient places to rest nearby.

Behavior of Pacific walruses in the St. Lawrence Island Polynia — a place of seasonal, shallow open water that is ringed by ice — is described in a newly published study by scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey and other institutions.

The area, south of the Bering Strait’s St. Lawrence Island, is the primary winter breeding ground for Pacific walruses. It holds the biggest winter concentration of walruses, though there are other regions off Alaska and Russia where the mammals congregate in winter, says the study, published in the April 9 issue of the open-access journal PLOS ONE.

Radio tracking

Walrus experts working on the study used a combination of radio tracking of the animals, aerial observations, satellite imagery of sea ice and pinch tests that sample parts of the sea sediments to see what food is in them. The data dates back to 2006.

The results about walrus movements and behavior were not surprising, said co-author Anthony Fischbach of the USGS Alaska Science Center. When all the data is combined, he said, “You find that they like to go places where it’s easier to move and the food is better.”

Fischbach and his colleagues found that though walruses need ice to rest on between searches for food, the walruses in the St. Lawrence Polynia are largely indifferent to the movements of floating pieces of ice when it comes to such searches. Instead of seeking food where floating ice might take them, the walruses are making dives in the precise places that appear to hold the most clams and worms, as measured by the grab tests.

The right combination of conditions for walruses in that area, it seems, is partially-open water in the middle of the polynia, covered in part by thin and loose ice that lingers far into the spring, with stable, thick ice nearby to provide platforms for hauling out and resting, he said.

The new study builds upon the biologists’ previous findings that ran counter to what Fischbach called the “lucky piece of ice” theory, which held that walruses rode around on floating ice to find food.

Understanding their world

The new study gives more information to understand the walruses’ world.

The ideal conditions for walruses in the St. Lawrence Polynia come when ice forms up at just the right time in the fall and lingers over the polynia, in thin form, until just the right time in the spring and summer, Fischbach said.

Fall ice freeze-up is important for the habitat of walrus prey, he said. The ice “drops its salt as it forms and it creates benthic communities that are favorable to many of the foods that walruses prey upon,” he said.

In the Bering Sea spring, if there is a thin layer of ice over the polynia’s water that lasts well into the season, sunlight will filter through to encourage biomass production, Fischbach said. If waters are cool enough, the small sea creatures that might eat that biomass will keep away, and ultimately the ungrazed biomass will sink down to the sediments to enrich the benthic habitat — the layers of sediment on the sea floor — that produces the clams and worms that walrus eat, he said.

But if the ice patterns are off, however, the benthic communities — and walrus food supplies — might suffer, though fish might thrive, Fischbach said.

Ice melt

If the ice melts too soon, the biomass gets gobbled up by copepods, the small crustaceans that swim in the water column and themselves are eaten by bigger fish, he said. Thus more ice-free conditions tend to favor creatures swimming in the pelagic zone rather than those in the benthic zone — the clams and sediment-burrowing creatures eaten by walruses.

If seasonal sea ice decreases as is projected, that could diminish habitat for walrus food and “could result in a northward shift in the wintering grounds of walruses in the northern Bering Sea,” the study says.

The scientists have also been studying impacts on walruses when summer and fall ice is sparser than normal. In those circumstances, walruses have been moving north and to shore, where land is used for haulouts in the absence of ice. Fischbach, USGS research ecologist Chad Jay and others have documented and filmed that behavior.

The study of the St. Lawrence Island Polynia has some drawbacks, Fischbach said. One concern is that the grab tests — pinches of sea sediment that are pulled up for examination — were no more than about 10 centimeters deep, he said. Walruses are known to forage three times that deep into sediments, so scientists had to make assumptions about the deeper benthic prey, he said.

Contact Yereth Rosen at yereth(at)alaskadispatch.com

Related Links:

Canada: Hunters asked to help set harvest limits in Canada’s eastern, CBC News

United States: Alaska – Yup’ik to receive aid after disastrous walrus hunt on remote island, Alaska Dispatch