Blog: North Korea and the Northern Sea Route

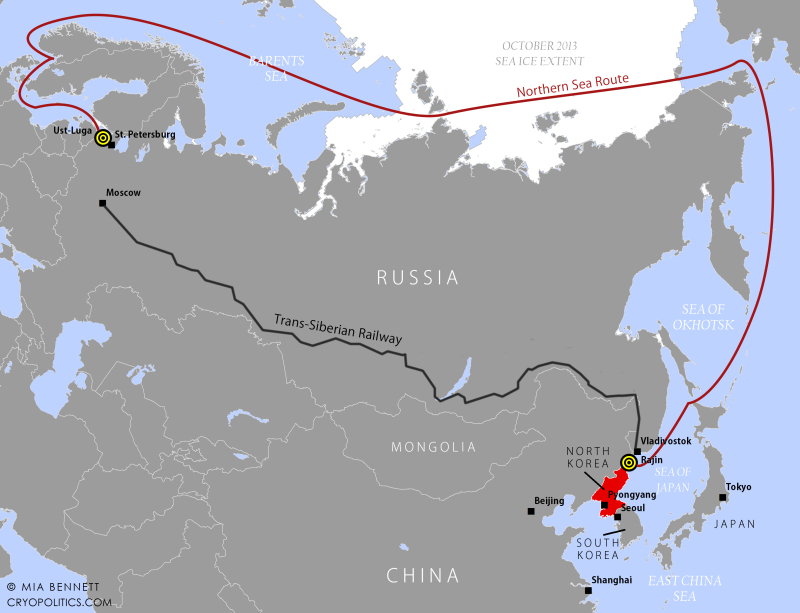

Last year, a total of three ships sailed from the Port of Ust-Luga, Russia along the Northern Sea Route (NSR).

A relatively new port on the Baltic Sea near St. Petersburg, Ust-Luga is the fastest growing port in Russia according to TransBaltic. By 2018, the port is predicted to be able to handle 180 million tons of cargo annually. By 2020, the port could become Russia’s largest. Two of the tankers were carrying shipments of naphtha, a hydrocarbon, to Yeosu, South Korea. One of them was notably the first pilot voyage of the NSR by South Korean chaebol Hyundai Heavy Shipping, which it accomplished with the assistance of Swedish company Stena Bulk.

Yet surprisingly little notice was paid to the voyage of the third ship from Ust-Luga, which occurred near the close of the Arctic shipping season. On October 25, Liberia-flagged HHL Hong Kong set sail from the Russian port. The ice-class 1A ship, operated by the Germany-based Hansa Heavy Lift, was carrying 1,742 tons of “general cargo,” according to the NSR Administration. The vessel entered the NSR at Kara Gate and departed at Cape Dezhnev on November 11 after nearly 17 days on the route, traveling an average of 6.7 knots – slightly slower than average. A quick search of Hansa Heavy Lift on Google resulted in this less-than-revealing SeaTradeGlobal news article announcing the fact that two of the company’s “ice-class vessels safely delivered their cargo to the Far East.”

The location in the Far East unmentioned in the article? Rajin, North Korea. Located on the country’s northeast coast, it’s the most northerly ice-free port in Asia. In 1991, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the DPRK designated the cities of Rajin and nearby Sonbong to be the “Rason Special Economic Zone.” Yet it is only since 2011, when China officially began participating in the zone’s development, that improvements have begun to pick up steam.

Deduced from the SeaTrade Global news article, the general cargo on board HHL Hong Kong en route to Rajin seems to have consisted of four 56-meter-tall, 400-tonne cranes. These cranes were possibly for use in building out Rajin’s port with Russia’s help. According to a March 2013 story from South Korean news agency Yonhap, in the past year or so, North Korea has increased its imports of cargo machinery in order to build out the port. A report from the Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency explains that Russia exported $21.16 million worth of jib cranes to North Korea last year, accounting for 22 percent of its exports to the country. The value of the crane shipments was worth more than Russia’s more typical oil and coal exports to the Hermit Kingdom. North Korea has reportedly leased dock Number 3 at Rajin to Russia, which is investing $66 million in upgrades to the dock and nearby infrastructure, such as the railway. The modernization of the port’s capabilities likely involves cranes such as the very ones transported by HHL Hong Kong.

The port of Rajin as a “logistics hub”

Yonhap states that Rajin could become a “logistics hub” if it is linked into the Trans-Siberian Railway. Already, there is a railway connecting Russia and North Korea via the crossing at the Tumen River (check out this blog for a fascinating account of two passengers’ journey by rail from Vienna to Pyongyang). In 2013, upgrades to the 54-kilometer railway from Khasan, the last town in Russia before the Tumen River crossing, to the port at Rajin were completed, fulfilling a 2008 agreement signed between the North Korean Ministry of Railways and Russian Railways. An impressive photo from AFP shows the ceremony that took place in September to commemorate the upgrades, complete with large cranes in the background.

With the upgraded rail link, Russia can now transport more containerized cargo through the port, which is envisioned to eventually be able to handle 4 million ton of cargo annually (though compare that to Ust Luga’s 180 million, and it’s clear that Russia is probably not planning for Rajin to become a major hub anytime soon). There are even dreams of eventually modernizing the railway all the way into Busan, the world’s fifth-busiest container port, in South Korea. Infrastructure, however, can’t just be upgraded once to magically function. It needs to be maintained, too – a major challenge for the DPRK.

While infrastructural linkages are better bridging North Korea and Russia, to really turn Rajin into a logistics hub would likely require massive changes to the political situation on the Korean Peninsula. So far, it seems that the only alterations have been negative. In the wake of the purge and subsequent assassination of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un’s uncle late last year, Yonhap reports that the country’s trade ties with China have soured. Beijing is reportedly no longer leasing the other two piers at the port, if it ever was. An earlier Joong Ang Daily article from November 2013 (ironically published around the same time as this Forbes article, which makes it sound as if Rason is open for business) called the Rason special economic zone a “ghost town.” Joong Ang Daily also claimed that construction on the Russian-owned pier had stopped, too. (The North Korean Economy Watch blog has more on the confusion surrounding Rason’s current status.)

Yet even if works within the special economic zone have temporarily stalled, the improved railway and maritime connections from the Port of Rajin are still notable developments worth considering in relation to the Arctic shipping network. As the map below shows, Rajin falls squarely within the group of ports in Northeast Asia at which ships transiting the NSR either arrived at or departed from in 2013. Three of these ports, Busan, Qingdao, and Tianjin, fall within the top 10 busiest container ports in the world.

The Mongolian dark horse

The dark horse in the story of Rajin’s errant modernization efforts is Mongolia. The landlocked country’s president, Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj, traveled to North Korea for a four-day visit in November, though he did not meet with Kim Jong-un. Blogger Scott LaFoy notes that the Mongolia-DPRK relationship could be driving at energy security, for Mongolia has oil but not refineries, while North Korea has refineries but little oil. According to Forbes, Ulaanbaatar-based company HBOil, which has a 20% stake in the DPRK’s state-dominated Korean Oil Exploration Corporation, is interested in investing in an oil refinery on North Korea’s west coast. The Seungri refinery within the Rason zone, built with Russian technology, seems a likely candidate, although it is on the east coast. Should the Rason special economic zone’s port and oil refinery together take off, this could amplify North Korea’s ability to benefit from its position at the eastern end of the NSR. The passage has the potential to turn into an Arctic energy corridor, with 2/3 of the vessels traveling eastbound last year carrying hydrocarbons (NSR Administration).

Mongolia and North Korea are two countries on the sub-Arctic’s periphery that could play a role in connecting the Arctic region to the economic powerhouses of East Asia, albeit decades down the line. The two peripheral countries are closer to the Arctic than China, Japan, and South Korea. These three countries are observers in the Arctic Council, but North Korea and Mongolia are not, though the latter has supposedly applied for observer status. As the Wall Street Journal notes, Rajin “has big potential as a port for landlocked east Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces.” With its northernmost latitude at 53°33′N, Heilongjiang is also China’s northernmost province and one sometimes mentioned by Chinese officials to bolster their country’s claims to be a “near-Arctic state.” Access to the port at Rajin would bring northeastern China that much closer to the Arctic via the NSR.

A long way yet to the poles

Despite the arrival of one ship from the NSR to the once moribund-looking port of Rajin last year, North Korea still has a long way to go before it catches up to its neighbor to the south. 500 miles down the east coast of the Korean Peninsula lies the Port of Busan, in South Korea, a country well on its way to becoming a fully-fledged polar state. It was here at the Yeongdo shipyard in 2009 that Hanjin Heavy Industries completed construction of one of the world’s most modern icebreakers: South Korea’s RV Araon. Given the intermittent modernization efforts of the Rason special economic zone, North Korea will not become a polar state with capabilities like those of South Korea anytime soon.

This post first appeared on Cryopolitics, an Arctic News and Analysis blog.