Arctic hamlet set to celebrate historic discovery of second Franklin expedition shipwreck

Residents of Gjoa Haven, a tiny Inuit hamlet in the Canadian Arctic, and the crew of a research vessel that located the “perfectly preserved” wreckage of one of two ships lost in an ill-fated 19th century Arctic expedition are throwing a big feast to celebrate their historic discovery.

The presumed wreckage of HMS Terror, which was abandoned in sea ice in 1848 during a failed attempt to sail through the Northwest Passage, was found on September 3 by the Arctic Research Foundation’s Martin Bergmann research vessel thanks to a tip from Sammy Kogvik, an Inuk Ranger and a native of Gjoa Haven, said Adrian Schimnowski, the foundation’s CEO and operations director.

It was located in the uncharted waters of coincidentally named Terror Bay on the south-west corner of King William Island in Nunavut, Canada’s northern most territory, Schimnowski said.

Following their discovery that is likely to rewrite one of the most dramatic chapters in the history of 19th century polar exploration, the 10-member crew of Martin Bergmann arrived in Gjoa Haven located on the southeastern coast of King William Island.

Proud community

“The community is buzzing with excitement right now,” said Schimnowski in a phone interview from Gjoa Haven.

The hamlet’s community hall was a hive of activity last night with the local band and performers practising, cooks preparing food for the feast, Schimnowski said.

“I think there is more people practising than ever before any other feast,” Schimnowski said. “Everyone is so excited, welcoming, very proud that Sammy Kogvik assisted Arctic Research Foundation in this great discovery.”

168-year-old mystery

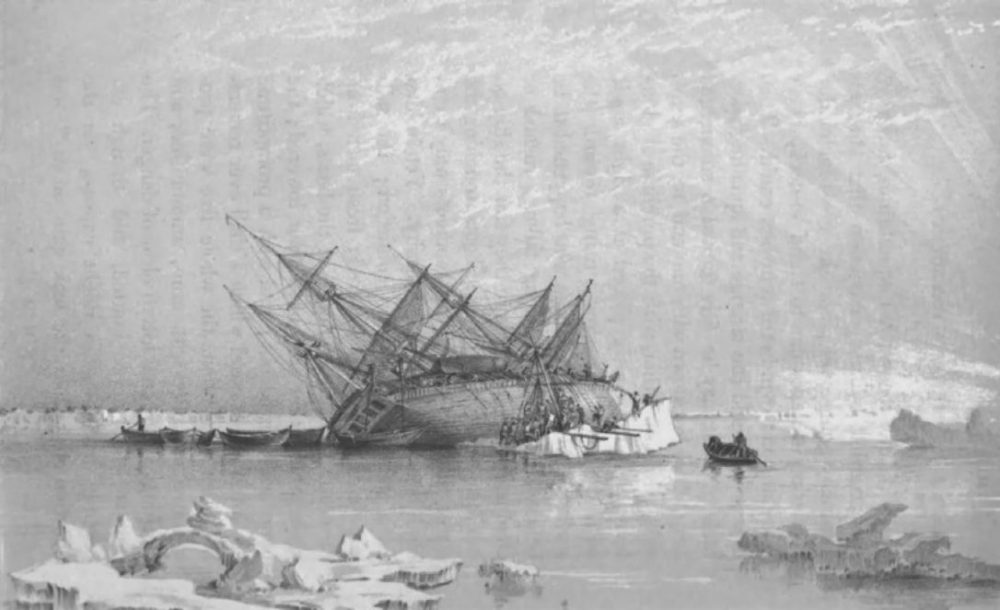

The mysterious disappearance of the 129-crew expedition, headed by Sir John Franklin, had bedevilled the Royal British Navy and generations of historians and polar explorers for almost 170 years.

Kogvik told his crew mates that while on a fishing trip near Terror Bay seven years ago, he stumbled upon a piece wooden mast sticking out of the sea.

But Kogvik kept his discovery secret, especially since his camera with the pictures of the piece of wood mysteriously disappeared, pointing to bad omens.

It wasn’t until a couple of weeks ago, that Kogvik felt comfortable enough to share his story with Schimnowski.

“I was excited to hear the story because this was another version of a story that I had heard in the past,” Schimnowski said, “a story where, if you look into the water during sunset, you’ll see a silhouette of a masted ship.”

As it happens, the research vessel was very close to Terror Bay already so the crew decided to change course and go into uncharted waters of the bay to investigate further, he said.

Once in Terror Bay, the Martin Bergmann deployed two smaller boats equipped with sonars to search the bay. But two hours of search didn’t produce any results and the crew, which was worried about missing a scheduled rendezvous with their partner vessels in Cambridge Bay, decided to call it a day.

The captain took a different path to get out of the bay, about 400 metres away from the vessel’s entry point into Terror Bay and the Martin Bergmann passed right over the wreck, Schimnowski said.

‘Needle in a haystack’

The ship’s sounder picked up a grainy image of a shipwreck lying 24 metres below the surface.

“It looked at first like it was a large school of fish, maybe a boulder,” Schimnowski said. “But it was much more than that, to me it looked like a cross section of a masted ship.”

The crew sent down a remote-controlled underwater vehicle operated by a Canadian Navy officer.

It captured video images of a well-preserved ship similar to Terror.

“It’s almost like finding a needle in a haystack,” Schimnowski said. “If we were a hundred metres to starboard or port on that route exiting Terror Bay, we would have not seen it on the sonar.”

The shipwreck lay on the sea floor with its three masts broken but still standing. Almost all hatches were closed and everything stowed.

“Every time we saw something new it was a big celebration, lots of man hugs, high-fives, cheering and we just wanted to see more,” Schimnowski said. “There was moments when we had tears in our eyes because we still couldn’t believe what we had found.”

Schimnowski said the crew are hundred per cent sure the wreckage is in fact HMS Terror.

The location of the discovery and the ship’s condition could have implications for historians’ understanding the fate of Franklin’s expedition.

Historians had long thought that the 105 surviving crew members had tried to march south after abandoning the ice-trapped ship.

But discovery of the HMS Terror with almost all the hatches battened down opens the possibility that at least some of the crew returned to the ship and attempted to sail it out of the frozen passage.

“My feeling is there might not be anyone on board this vessel,” Schimnowski said. “It looked very intentional that the ship was winterized. Inside the ship there were very few artefacts, the artefacts that were there were left in the same way 170 years ago: plates and dishes are stowed with flaps holding them in place, the spice bottles are still on the shelves.”

Judging from the data they were able to collect so far, Schimnowski said they are speculating that the ship was intentionally left for the winter.

The next step would be an archaeological survey of the ship by marine archaeologists working for Parks Canada, the federal agency that manages Canada’s national parks and historic sites.

“It’s the Parks Canada team that will do a detailed analysis, almost like a forensic study,” Schimnowski said. “Each artifact, each image on the screen will be a clue that will lead to (understanding) why the ship sank, what happened to the men, it’s like a detective story.”

Parks Canada is excited about the reports of the discovery of the wreck, the agency said in a statement emailed to RCI.

“Parks Canada, in partnership with the Canadian Coast Guard, will validate the find at the earliest operational window. Once confirmed, the Government of Canada will discuss the protection of the site with the Government of Nunavut and its Inuit partners,” Parks Canada said in the statement.

“Locating the HMS Terror is only the initial step of the research that will need to be conducted. Parks Canada’s Underwater Archeology team, along with the Canadian Coast Guard, the Canadian Hydrographic Service, the Royal Canadian Navy, and other partners, will investigate this new wreck site on future missions to reveal more details and develop a better understanding of this important story for Canada and the world.”

Inuit oral history was also instrumental in the 2014 find of HMS Erebus. Historian Louis Kamookak helped researchers pinpoint the location of the wreck after recounting a story passed down generations saying that one of the ships [HMS Terror] was crushed in ice northwest of King William Island, while another [HMS Erebus] drifted and sank further south, where it was ultimately found.

Ownership of both shipwrecks has been transferred from Britain to the Canadian government, and their resting spots are considered historic sites.

With files from Garrett Hinchey of CBC News

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Found at last! Franklin ship lost for 166 years, Radio Canada International

Finland: WWF Finland concerned about oil leak from shipwreck in Baltic Sea, Yle News

Norway: Norway returns Inuit artifacts to Arctic Canadian community, CBC News

United States: IDs made in 1952 Alaska plane crash, Alaska Dispatch