North and South poles post low sea ice extent in December: NSIDC

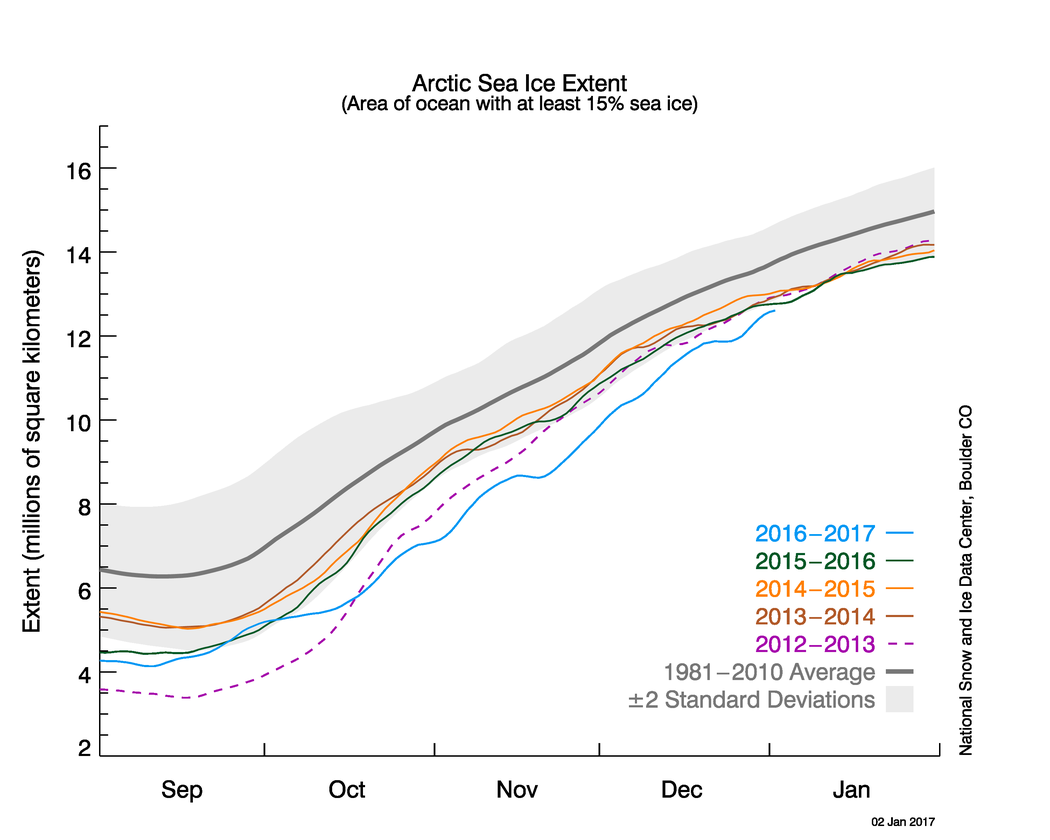

Sea ice in the Arctic and the Antarctic set record low extents every day in December, according to the latest report by the U.S.-based National Snow and Ice Data Center.

December numbers continued the pattern that began in November, setting a record low for the month ever since satellite observation of ice extent began in the late 1970s.

“This is really a pattern that we’ve seen all year, ever since we started with a spring maximum in extent in March,” said Mark Serreze, director of the NSIDC. “All the way through summer until now, we’ve been either at record lows or ranking No. 2. It’s been a pretty remarkable year.”

‘Rapid transition’

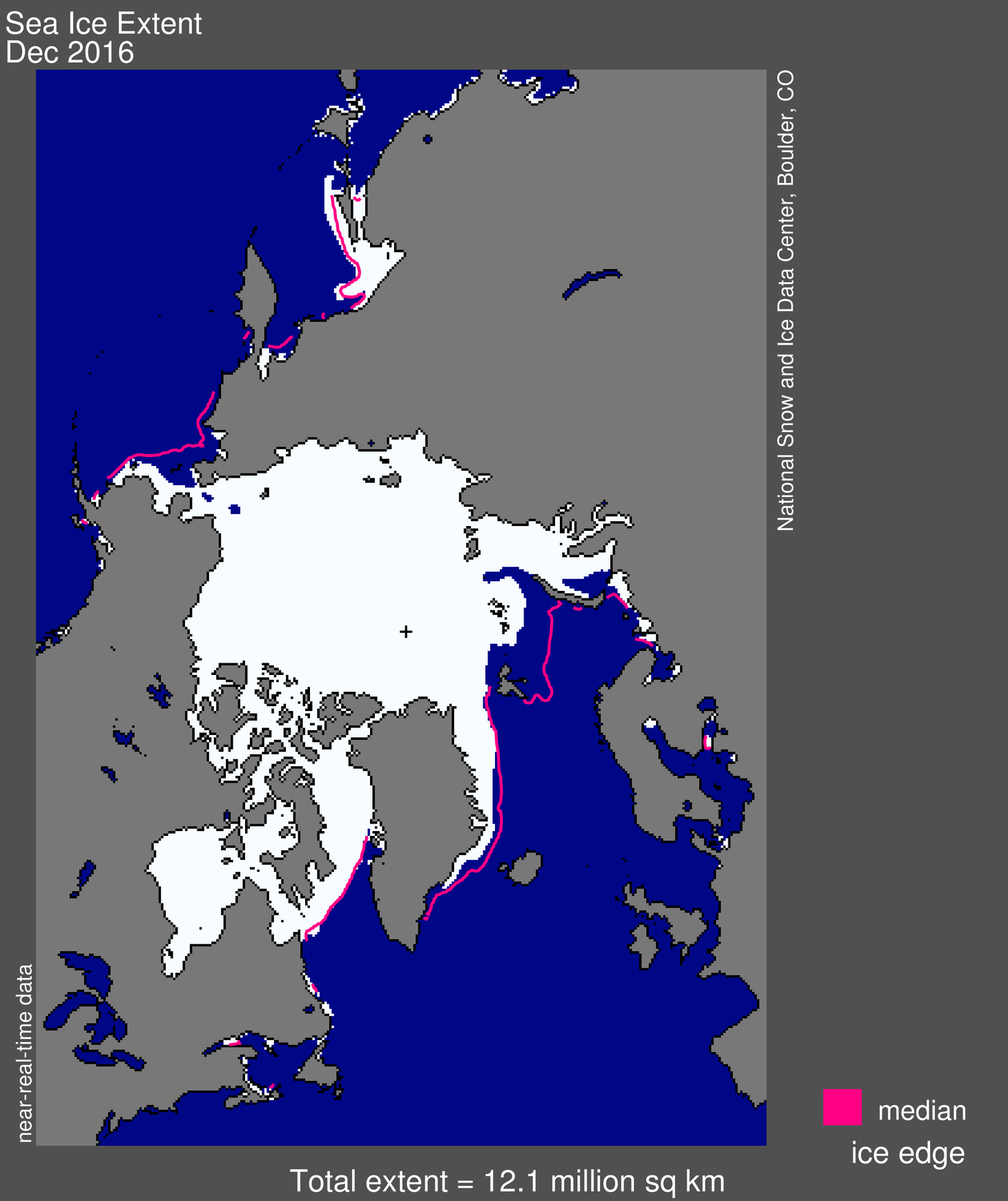

Arctic sea ice extent for December 2016 averaged 12.10 million square kilometers (4.67 million square miles), the second lowest December extent in the satellite record, according to the NSIDC report. That’s just 20,000 square kilometers (7,700 square miles) above December 2010, the lowest December extent.

In fact, according to the NSIDC, December’s ice extent was 1.03 million square kilometers (397,700 square miles) below the December 1981 to 2010 long-term average.

“These numbers tell me that we really are in a very rapid transition phase,” said Serreze.

While most of the media attention has been focused on the extremely low sea ice conditions at the end of the melt season in September, researchers now see these low sea ice conditions extending into other seasons as well, Serreze said.

“The changes that we’ve seen, especially this year, are really just… I would call them exclamation points on what I think is a remarkable transformation of the Arctic,” Serreze said.

Ice growth picks up in December

However, Serreze said he expects ice extent to start growing fast again now that the unusual warmth has left the Arctic and the ocean has finally cooled down.

In fact, the rate of ice growth for December was 90,000 square kilometers (34,700 square miles) per day, according to the NSIDS.

This is faster than the long-term average of 64,100 square kilometers (24,700 square miles) per day. As a result, extent for December was not as far below average as was the case in November. Ice growth for December occurred primarily within the Chukchi Sea, Kara Sea, and Hudson Bay—areas that experienced a late seasonal freeze-up, the NSIDC report said.

Loss of multiyear ice

“But what’s going to happen is whatever ice we form now is going to be fairly thin ice,” Serreze said. “And that means that starting with all that thin ice in the spring, that’s the stuff that’s going to melt out in the summer.”

Walt Meier, a research scientist at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory, said what worries him is the general trend of seeing less and less sea ice throughout the year and the rapid loss of the multiyear ice, which unlike seasonal ice grows throughout several winters.

“What we see is ice cover in the Arctic at the end of winter, covered mostly by first-year ice that’s in order of 1 to 2 metres thick, as opposed to an Arctic Ocean back in the 1980s that was covered mostly by multiyear ice that’s 3 to 4 metres thick,” Meier said.

Moreover, it seems this multiyear ice, which used to melt only once ocean currents carried it into the North Atlantic, now can melt in the Arctic Ocean itself, he said.

‘Dramatically changing ecosystem’

This change in the quality of ice cover can have an adverse effect on animal species, such as polar bears and seals that need the ice to survive.

On the other hand, the open waters of the Arctic Ocean in the summer provide a new habitat for other ocean animals: from organisms like algae to new bird and fish species venturing further north.

“We’re seeing a really pretty dramatically changing ecosystem in the Arctic because of the loss of summer sea ice,” Meier said.

‘What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic’

Researchers are also looking into what the loss of multiyear ice that doesn’t melt in the summer means for the rest of the planet, he said.

With less multiyear ice and more seasonal ice, which melts during the summer, the ocean absorbs more heat, feeding that heat into the atmosphere in the fall and even into the winter, he said.

“Unlike Las Vegas, what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic,” Meier said. “That change in the Arctic atmosphere and Arctic circulation and winds, and so forth that can have effects outside of the Arctic.”

While there is still some debate in the scientific community about just how much do the changes in the Arctic affect climate and weather patterns in more southern latitudes, several studies point to linkages between climate change in the Arctic and more extreme weather events further south.

“The way this works is that you have this cold air normally in the Arctic and now it’s not so cold and that less cold air can more easily spill out into the south, it can more easily kink the Jetstream, which tends to run in a circular pattern around the Arctic regions,” Meier said. “So we’re seeing more loopiness in the Jetstream. And that loopier Jetstream can cause more extreme weather.”

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Warmer Arctic Ocean temperatures delay sea ice formation, Radio Canada International

Finland: Puzzling migration fluke brings thousands of Siberian birds to Finland, Yle News

Greenland: New model predicts flow of Greenland’s glaciers, Alaska Dispatch News

Norway: Record heat sends shockwave through Arctic, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Ancient virus found in Arctic permafrost, Alaska Dispatch News

Sweden: Sweden’s climate minister worried about Trump’s stance on global warming, Radio Sweden

United States: Alaska: Barrow’s record-warm October continues pattern associated with low sea ice, Alaska Dispatch News