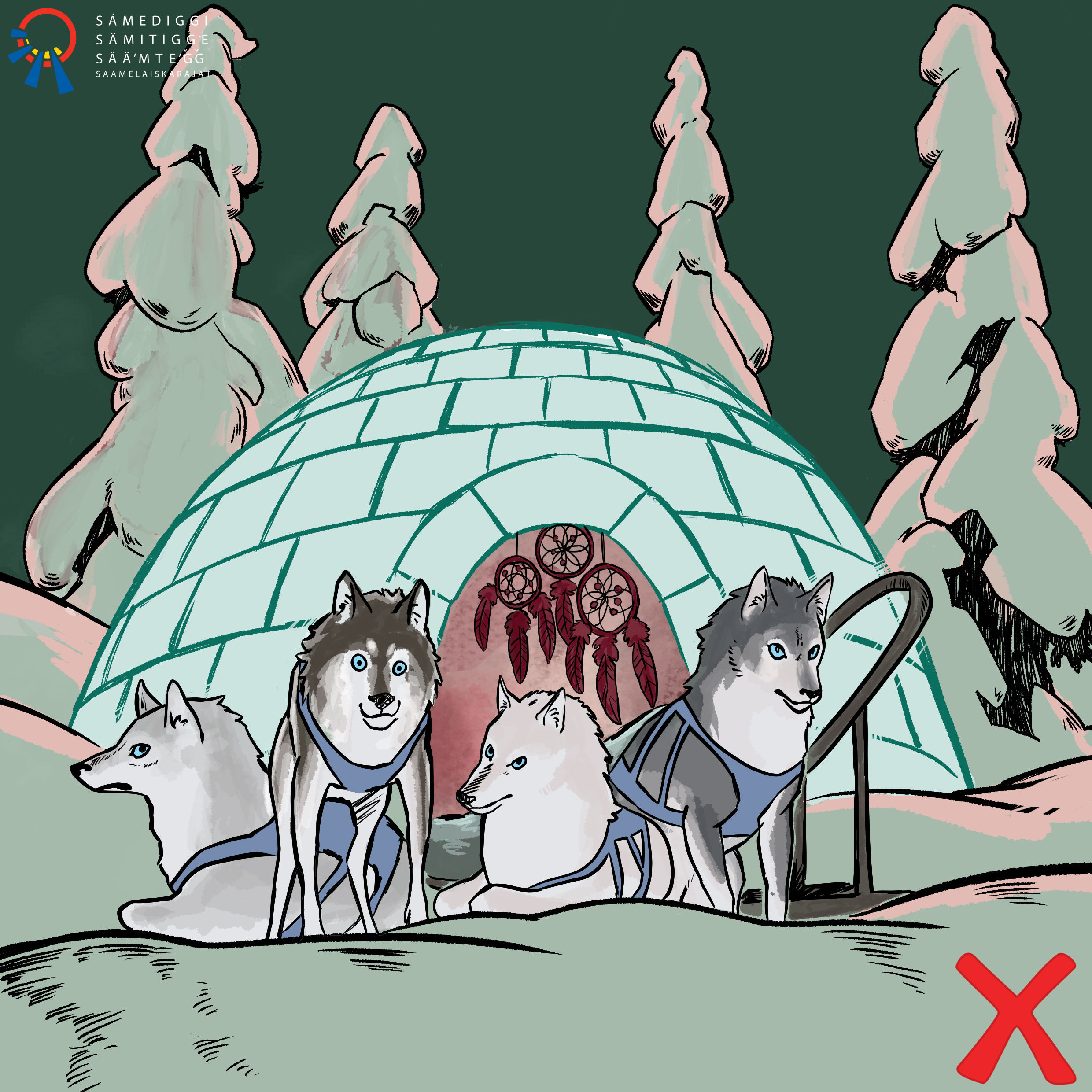

Illustration showing an example of destructive Sami stereotypes for the Sami Parliament in Finland’s Culturally Responsible Sami Tourism project.

(Artist: Sunna Kitti/Courtesy Sami Parliament in Finland.)

INARI, Finland - Travelling around Finnish Lapland can feel a lot like a throwback to Arctic Canada at times.

There’s the glass igloos peaking through the trees at the Kakslauttanen Arctic Resort just off the E75 road, or the umteen signs in Arctic villages like Inari advertising dog team excursions, billed here as “husky safaris.”

For many people, igloos and dog teams are synonymous with the Inuit culture found in Canada, Alaska, Greenland and Russia, yet symbols like these have been used to market Arctic Finland to tourists for decades. And this despite the fact that the region is part of the homeland of the Sami - an Indigenous people and culture that has nothing to do with the Inuit way of life thousands of kilometres away.

But while the proliferation of Inuit symbols used to market Arctic Finland may do little more than raise a few eyebrows for some visitors, there’s also a darker side to marketing Arctic tourism in this country - the omission, and misuse of Sami symbols and culture in promoting the region - something that goes back decades.

“The existing, primitivised and misleading widely-spread representation of the Sami in tourism utilising Saminess in Finland is, at its worst, insulting for and/or commodifying of the Sámi community,” the Sami Parliament in Finland, the body that represents the approximately 10,000 Sami in the country, says in a statement on their website.

“This repeatedly presented, public, misleading image negatively affects the vitality of the Sami culture. It is hard for the Sami community alone to provide correct and authentic Sami presentation with limited resources.”

As well as cultural impacts, there’s also environmental impacts by everything from foreign hunters interfering with traditional Sami activities like hunting, fishing and reindeer herding, to husky safaris (dog mushing trips) that disturb reindeer and Sami reindeer herding dogs.

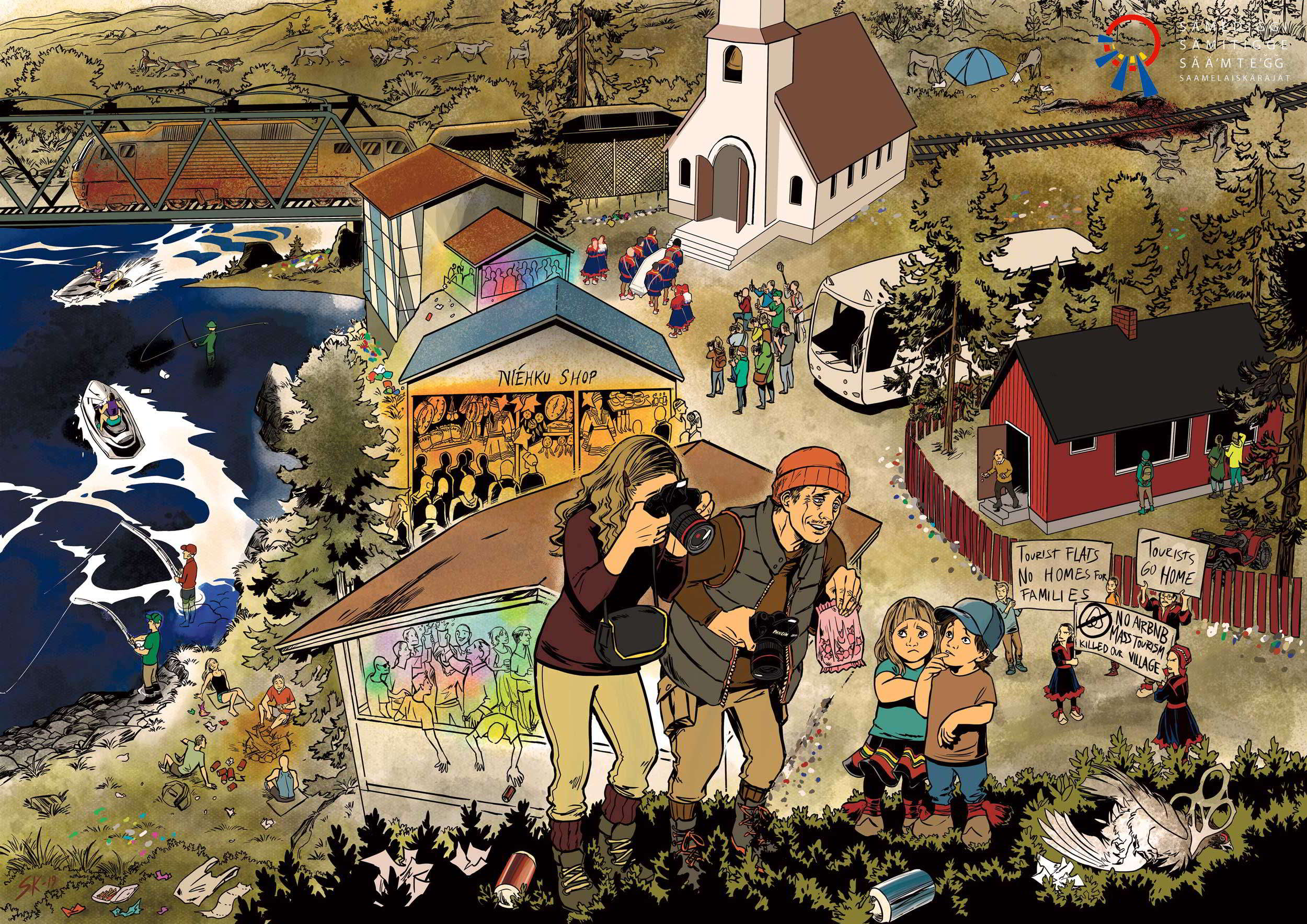

(Artist: Sunna Kitti/Courtesy Sami Parliament in Finland)

Jussa Seurujarvi, a reindeer herder from Partakko, a village in Arctic Finland, says he’s lucky his community is off the tourism radar for the moment, but that other, larger Sami communities, haven’t been so lucky.

“Tourists come and take pictures in your garden or back yard,” he says. “Even the Sami kindergarten has had issues with tourists because they think it’s a souvenir shop and they can come and take pictures.

“I think Lapland shouldn’t be marketed for mass tourism. It should be marketed as an exclusive place to travel to lessen negative environment and culture impacts.”

But now, Sami authorities in Finland are urging travellers to ditch their support of questionable tourism activities, learn that igloos and huskies have nothing to with Indigenous life in Finland, and get to know authentic Sami culture in their place.

In 2018, they launched the Culturally Responsible Sami Tourism project, a set of guidelines available in Finnish and Sami languages posted on the Sami Parliament of Finland website to educate tourism businesses and tourism students. (The guidelines are currently available in four languages: Finnish, North Sami, Inari Sami and Skolt Sami. Versions in English and other languages are being worked on.)

The seven principles cover everything from obtaining consent before photographing a Sami person going about their everyday life, to avoiding the use of Sami people or culture as exotic props in marketing materials.

Undoing destructive stereotypes

Sajos, the Sami cultural and administrative centre and home to the Sami Parliament of Finland in the village of Inari.

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

The Sami are an Arctic Indigenous people whose traditional homeland spans the Arctic regions of Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Kola Peninsula in Russia’s western Arctic, an area they refer to as Sapmi.

The birth of Lapland’s tourism boom can be traced back to 1950, when former U.S. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited Arctic Finland.

Rovaniemi, a city that is now Lapland’s administrative capital, had been almost razed to the ground in WWII. UNICEF, an organization Roosevelt was heavily involved in, was active in post-war rebuilding efforts.

A cabin built in her honour eventually became the birthplace of Rovaniemi’s Santa Claus Village, the city’s main attraction that now draws an approximately 500,000 visitors per year.

But Roosevelt’s visit is also often frequently described by locals as ground zero for some of the harmful tourism practises that endure to this day.

It’s said that local Finnish authorities, desperate to show Roosevelt something exotic in a region that had been completely ravaged by war, got people to dress up as Sami, creating an image that the international community would forever have of the culture -- someone (usually a Finn - although the historical record is unclear if the people in the photos were actually ethnic Finnish reindeer herders, or non-reindeer herding Finns) dressed up as a Sami with a lavvu (traditional tent) and a reindeer nearby — a stereotype that endures to this day.

Many Sami consider this harmful as it negates the rich hunting, gathering and fishing components of their culture, and causes outsiders to question their “Sami-ness” if they don’t fit the stereotype. (In fact, the majority of Sami in Finland today do not own, or engage in reindeer herding.)

(Sámediggi/Saamelaiskäräjät/The Sámi Parliament)

“I’ve talked with Sami on the Norwegian side of the border and hear they too suffer from the stereotype created in Finland years ago.” Suomi says. “Because like here in Inari, tourists come up to them saying ‘Where can we find the Sami people?’ And if the person they’re speaking to chooses to say ‘Well, I am one,’ the person will say, ‘You can’t be, you don’t have the Sami dress or you’re not with a reindeer.’”

(Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

Visit Finland, Finland’s national tourism organization, has also got involved to circulate the guidelines as widely as possible, they say. The guidelines have been posted in the business section of their website, and circulated on social media, in newsletters and seminars, and have been included in Visit Finland’s ‘Sustainable Travel Finland’ educational workshop. The guidelines have also been included in the ‘Sustainable Travel Finland’ e-learning package that targets international tour operators and travel agencies.

“With these attempts we aim to make (the) travel industry aware of the ethically responsible Sami tourism, and eliminate the unethical use of Sami culture in tourism industry – the goals we share with Sami Parliament.” says Liisa Kokkarinen, Visit Finland’s regional manager for Destination Finland, and who manages the Sustainable Arctic Destination project. “We also hope to make people more aware of authentic, modern Sami culture in general, instead of upholding a romanticized image of a culture from the past.

“Whenever we are made aware of unethical Sami tourism practices in Finland, whether conducted by a tour operators operating in Finland or by a Finnish tourism company based in Finland, we do contact the company and discuss the principles of ethically responsible Sami tourism with the company in question. Luckily these cases are rare, and usually a simple discussion helps – oftentimes companies seem not to have realized their actions are viewed as unethical.”

Using cartoons to educate

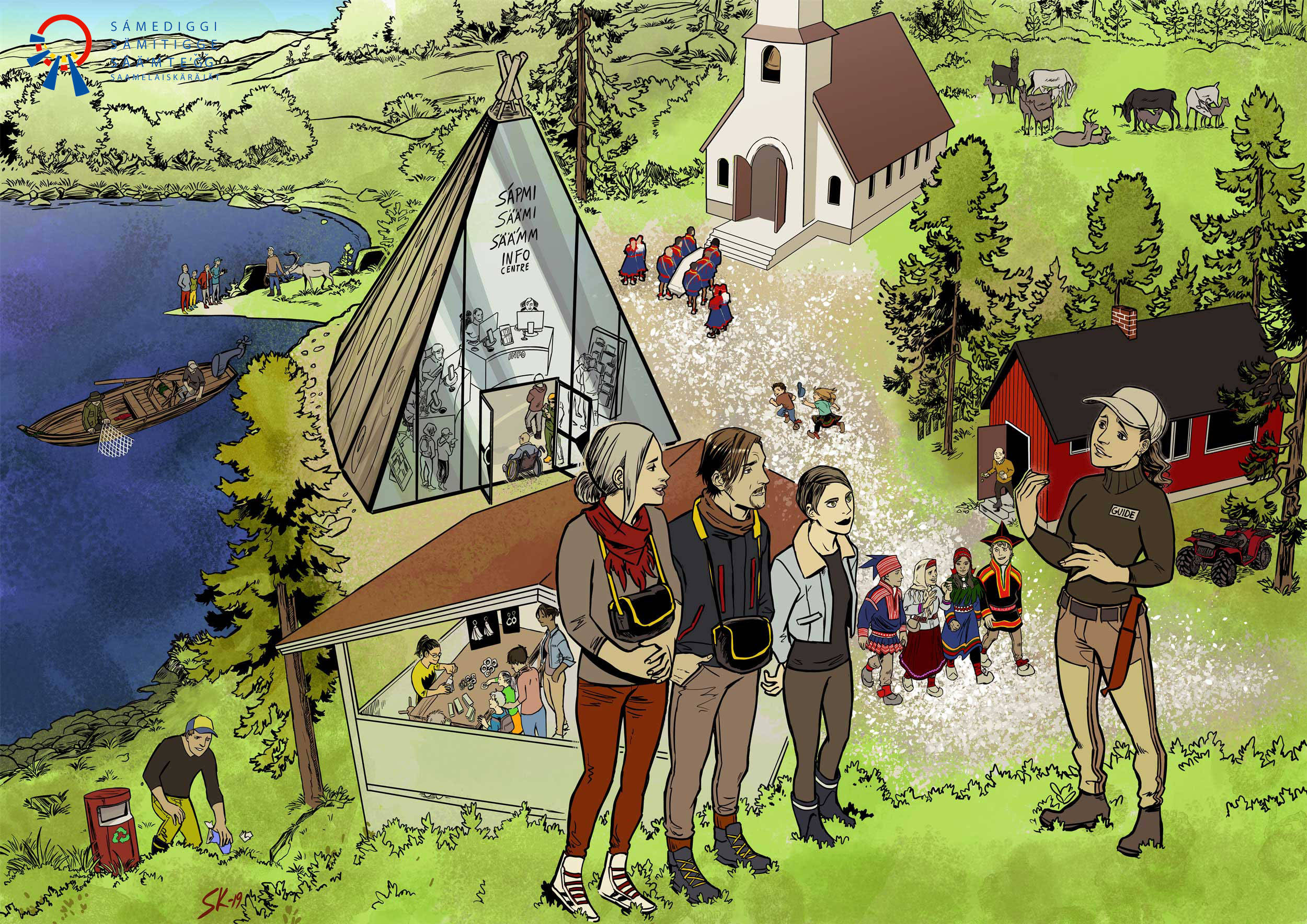

Sami artist Sunna Kitti created artwork for the Sami Parliament in Finland’s Culturally Responsible Sami Tourism project.

In this image, an example of destructive Sami stereotypes are depicted on the left, while a positive depiction of Sami culture is depicted on the right.

(Artist: Sunna Kitti/Courtesy Sami Parliament in Finland.)

The cartoons depict a wide variety of situations with a big red X on the pictures considered “Dont's” and big green check marks on the pictures that are considered “Dos” when it comes to tourism in Lapland.

They cover everything from the proper ways to respect the environment to the kinds of tourism products that misappropriate Sami culture and that travellers should stay away from.

“We didn’t depict any particular company or companies.” Suomi said. “First because they change so often and there's more and more foreign companies. That’s why education is needed because now it’s not just Finns doing this, but people that come from abroad to work in tourism in Arctic Finland and do the same thing.

“And in the end, it’s not about targeting a particular company, it’s about changing a mindset.”

(Artist Sunna Kitti/Courtesy Sami Parliament in Finland)

Wildlife “Dont's”

One of the cartoons commissioned as a “Don’t” in the Culturally Responsible Sami Tourism project by the Sami Parliament in Finland.

Section 42 of Finland’s Reindeer act prohibits frightening reindeer, but this cartoon depicts a scenario that happens all too often, says Kirsi Suomi from the Sami Parliament in Finland.

“You see this quite a lot in the summertime.” she says.

“The reindeer run away from insects and they get very tired and hot and rest at the side of the roads. Tourists see that and try to move closer to them. Then when they see the reindeer are not moving, because the animals are so tired, they try to sneak up on them even more with their mobile phones. They just keep going closer and closer until the exhausted animal runs away. But you’re not allowed to do that.”

Sunna Kitti was the Sami artist hired to create the artwork for the project.

Kitti, originally from Arctic Finland but now based in the city of Turku in southern Finland, was already well known for her graphic novels and artwork focusing on modern representations of Sami culture.

“The image of the dirty indigenous person is unfortunately very stereotypical and alive and well here in Finland.” Kitti said. “The stereotypes around Sami people were created by people that didn’t think too highly of Sami people. We were considered primitive, unsophisticated or wild. That’s why I want to push back against these stereotypes because I see them as harmful."

Kitti says working on this project was rewarding both personally and artistically.

(Courtesy Sunna Kitti)

Preparing for the Arctic tourism boom

Artist Sunna Kitti’s rendering of negative tourism development in Sami communities.

(Artist: Sunna Kitti/Courtesy Sami Parliament in Finland)

Artist Sunna Kitti’s rendering of positive tourism development in Sami communities.

(Artist: Sunna Kitti/Courtesy Sami Parliament in Finland)

Tourism experts say that what’s going on in Finland is a microcosm of what might be in store for other Arctic regions as tourism ramps up in the North.

The Culturally Sensitive Tourism in the Arctic (ARCTISEN) project, started by researchers in Arctic Finland, seeks to create a support system for small and medium-sized tourist businesses to craft tourism products that accurately reflect and benefit the North. It was started around four years ago by researchers at Finland’s University of Lapland.

“We were a little bit tired of the tourism industry exploiting Sami culture so we got together to start discussing it, then we started inviting more and more people.” says Outi Kugapi, the ARCTISEN project manager.

Now, project partners include researchers from Canada, Finland, Greenland/Denmark, Norway and Sweden amongst others.

“This is the right time to have this kind of a project.” Kugapi says. “Interest in the Arctic keeps growing and it’s important that local Arctic cultures, whether they are Indigneous or non-Indigneous, are respected. Creating sustainable tourism ensures both business and local economies can benefit.”

Bryan Grimwood, an associate professor at Canada’s University of Waterloo is part of the ARCTISEN project and says Canada needs to be more proactive when it comes to tourism development in the North.

“Because Canada’s Arctic is still so expensive and hard to get to, communities are still somewhat protected.” Grimwood said. “But we still need to start talking about this now because the situation is complex. Canada has so many differing Inuit, First Nations, and Métis cultures, and what is acceptable in one would not be acceptable in others.

“But even more than talking, I think it’s time for us to be listening to Indigenous communities and listening to their expectations around tourism and land use. Because in a lot of cases, they’ve been stating this for some time, but maybe just haven’t been given their due.”

How not to promote Arctic tourism was published on February 3, 2020.

About

Eilís Quinn is a journalist and manages Radio Canada International’s Eye on the Arctic circumpolar news project. At Eye on the Arctic, Eilís has produced documentary and multimedia series about climate change and the issues facing Indigenous peoples in the circumpolar world. Her documentary Bridging the Divide was a finalist at the 2012 Webby Awards. Eilís began reporting on the North in 2001.

Her work as a reporter in Canada and the United States, and as TV host for the Discovery/BBC Worldwide series Best in China, has taken her to some of the world’s coldest regions including the Tibetan mountains, Greenland and Alaska; along with the Arctic regions of Canada, Russia, Norway and Iceland.

Twitter : @Arctic_EQ

Email : Eilís Quinn