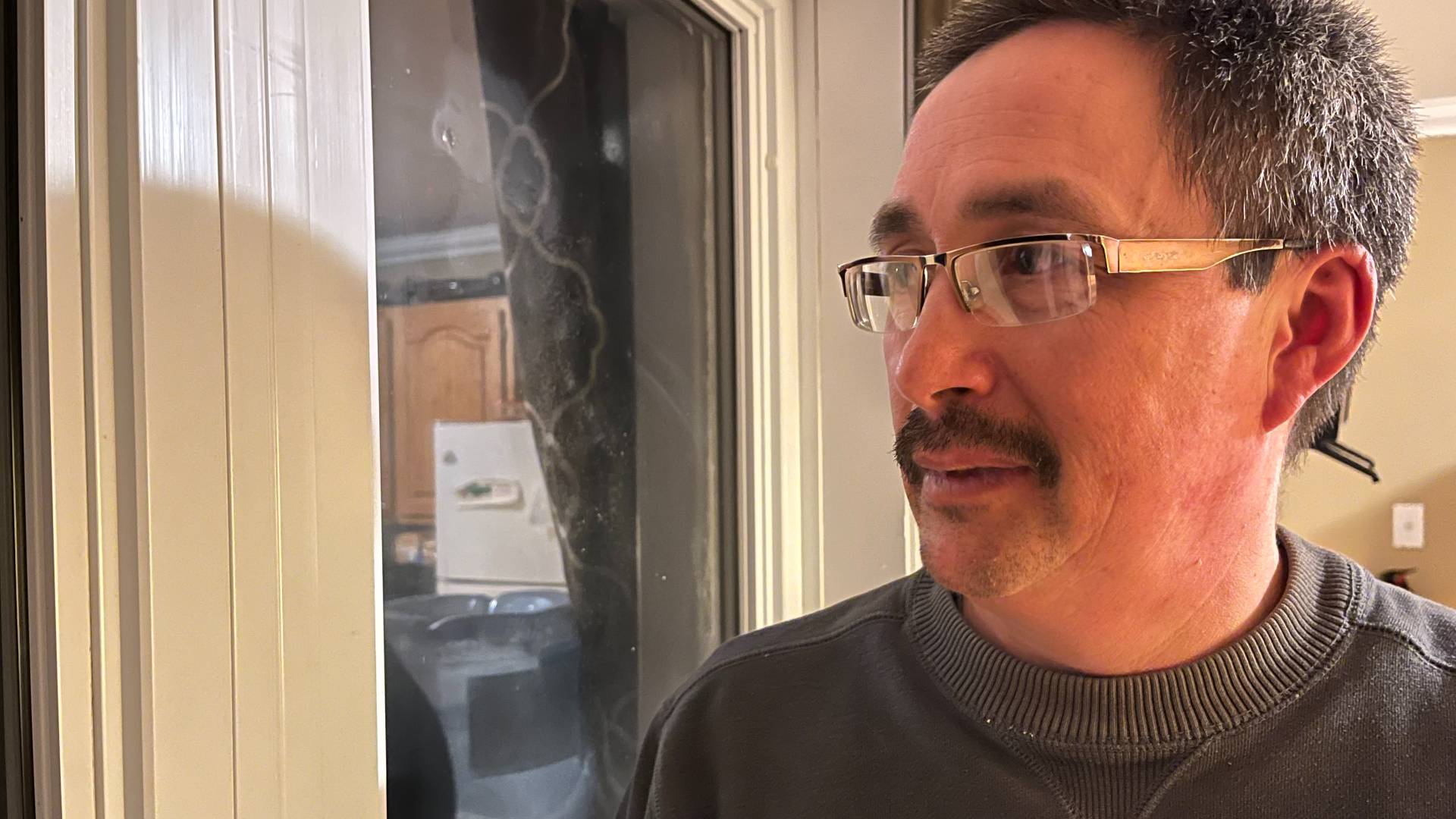

“You’re working for the safety and security of your country, that’s why I’m involved,” says Commander Oswald Allen (left) pictured here with Second-in-Command Master Corporal Levi Wolfrey (right) of the Canadian Rangers Rigolet Patrol in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. (Eilis Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

RIGOLET, Newfoundland and Labrador – Oswald Allen and Levi Wolfrey remember the day more than two decades ago that they heard the Canadian Rangers were looking for members and decided to go and check it out.

“They wanted people that knew the land, where to go and not go, so when [the military] came here to recruit, we both went together,” Wolfrey said.

Allen said he was immediately intrigued.

“It seemed like a cool thing to do and I joined to see what it was like,” he said.

Now commander in charge of the 18-person Canadian Rangers patrol in Rigolet, the world’s most southerly Inuit community, Allen gets serious when asked about what’s kept him with the Rangers for the last 23 years.

“ You learn about so many different things in the Rangers,” Allen said. “You’re working for the safety and security of your country, that’s why I’m involved.”

Rangers mark their 75th anniversary

The Canadian Rangers are part-time reservists within the Canadian Armed Forces. Rangers are not trained combat soldiers, but with their knowledge of their local environments and ability to easily navigate in the country’s harshest and most challenging regions, act as the military’s presence.

There are approximately 5,000 Rangers located in 200 of Canada's most remote and isolated communities. The majority of the communities, located in the North and on the country’s east and west coasts, are Indigenous. Founded in May 1947, the Rangers are marking their 75th anniversary this year, and experts say it’s an important milestone to reflect on their role in Canada.

“The Rangers are a very distinct form of service in that they are considered trained upon enrollment,” Whitney Lackenbauer, Canada Research Chair in the Study of the Canadian North, and a professor at the School for the Study of Canada at Trent University said. “It’s their ability to harness all of their local and traditional knowledge, skills and expertise that makes them such a wonderful contribution, not only to Canadian security, but also community resilience.”

The Canadian Rangers were created during World War II, partly modeled on the Home Guard, the United Kingdom’s volunteer civilian militia put together as a back up to the regular forces should Nazi Germany try to invade Britian.

After Japan entered the war in 1941, concerns emerged about the vulnerability of Canada’s rugged and sparsely populated Pacific coastline. The Pacific Coast Militia Rangers (the PCMR), were created in 1942 to protect and patrol the isolated regions and were made up of locals like loggers or trappers that had intimate knowledge of the remote and rugged terrain. At its height it had some 15,000 members in British Columbia and Yukon. PCMR was stood down after the war, but its model was used to create the Canadian Rangers enabling the military to have a presence all along Canada’s coastlines.

“Who better than people living in an area, who know their homeland intimately, to be able to detect an anomaly when something's off?” said Lackenbauer, also an author of several books about the Canadian Rangers and Honorary Lieutenant Colonel of 1st Canadian Ranger Patrol Group from 2014-2020.

Whitney Lackenbauer, Canada Research Chair in the Study of the Canadian North

Working with local and military expertise

Cyril Lane, a Ranger who grew up in Postville in Labrador and now lives about 40 kilometres to the northeast in the community of Makkovik, says the Rangers’ fusion of local knowledge with military expertise enriches everyone.

“Growing up I learned how to read the weather and survive out on the land from my father and my uncles,” Lane said.

“If you look outside, you’ll see different things than me. I can recognize traditional travel routes where you'll just see a forest because you don’t know what to look for. That’s what we can bring to the military. But we also learn from them things like navigating with a compass and GPS.

Cyril Lane, Ranger

Allen from Rigolet agrees saying the ongoing Ranger trainings with the military keep both sides up-to-date on their different areas of expertise and is why he still finds being in the Rangers so valuable

“I learned from my father that if you go just North of here and hear the ice groaning, you better watch out and not go out too far because it could break up and you could end up stranded out there. The military doesn’t know that, and that’s why they got us.”

Rigolet, Newfoundland and Labrador. March 2022. (Eilís Quinn/Eye on the Arctic)

The Rangers are tasked with reporting anything they see that’s out of the order in the lands and waters around their communities. Other roles encompass everything from inspecting North Warning System sites for things like storm damage to disaster relief and response to performing search and rescue operations or participating in community events.

They also help supervise activities with the Junior Rangers, a youth program started in the mid-1990s, to teach traditional and life skills, as well as Ranger activities.

Over the last two years, they’ve also been key in the COVID-19 response across northern Canada whether it concerned setting up tents and other health care infrastructure in Nunavik, Quebec or delivering food and medicine in the Northwest Territories.

Peter Kikkert, assistant professor of public policy and governance at St. Francis Xavier University and the Irving Shipbuilding Chair in Arctic Policy at the Brian Mulroney Institute of Government, says the Canadian Rangers’ knowledge of their lands is well known, but that their role liaising with people or organizations coming north during a crisis is just as important but often overlooked.

“One of the fundamental aspects of how well communities do during an emergency or a disaster is the amount of social capital or social networks you can draw upon,” Kikkert said.

“The Rangers are a trusted organization in their communities and are at the nexus of all sorts of relationships and that makes them ideal for disaster response. Because if you’re an outside agency coming in to respond, if you talk to a Ranger, they can tell you who’s in charge of what, where to find what you need and who might be vulnerable and need immediate assistance.”

Kikkert says as climate change increases environmental disasters, he’d like to see more exercises between Rangers and other agencies to better prepare.

“Training and exercising for emergencies and disaster events continues to be a major part of what the Rangers do. But I think increased training for the role of Rangers during things like wildfires or floods or a community evacuation that could come back across the five Ranger patrol groups would be of great benefit, especially as we see the numbers of disasters increasing across the country.

“Those exercises that could help hammer out the roles and responsibilities between the Rangers, local police force, the hamlet office and the local fire department and I think it would be enormously beneficial.”

Model for other northern regions?

Lackenbauer says the success of the Rangers is also attracting international attention with other northern regions increasingly inquiring about replicating the Canadian Ranger model in their own territories.

“I’ve met with Alaskan individuals about it, the Canadian military have met with their counterparts about it at times who’ve expressed interest in exploring having something like the Rangers as part of their overall security tapestry.”

Lackenbauer says Greenland has also been interested in the Rangers.

“I was at their constitutional committee a few weeks ago and sat down with their working group on Foreign Affairs and security and almost the entire conversation was about the Canadian Rangers as offering a potential model if they ever do something like that in Greenland.”

Looking ahead

Regional, local and national commemorations to mark the Rangers' 75th anniversary will take place throughout Canada this year, with a big kick-off celebration in Victoria, British Columbia this month.

The Canadian Rangers 75th Anniversary Rendezvous will run May 20-23 and bring 100 Rangers from across the country together for a series of events.

On May 23, the anniversary day of the Rangers' founding, a ceremony will be held. Canadian Armed Forces Chief of Defence Staff General Wayne Eyre and Minister of National Defence Anita Anand, among other dignitaries, are scheduled to attend.

Lackenbauer says the anniversary is an important time for all Canadians to acknowledge the Rangers’ work and role in the country.

“The Canadian Rangers is such a uniquely Canadian creation, reflecting the tremendous diversity of so many different remote regions,” he said.

“They are very much respected for what they bring and it’s become a unifying symbol that’s harnessed all this diversity as military experts that allows us to celebrate and amplify all those wonderful skills that are already out there.”

Lane agrees and says even after more than two decades of service with the Rangers he still gets tremendous gratification from putting on the Rangers’ signature red hoodie whether it’s for an operation, a training exercise or community event.

“Being a Ranger isn’t a walk in the park,” he said. “You have to enjoy challenges, accept challenges and grow with the challenges. But I enjoy the camaraderie, the opportunities and sense of accomplishment. Just putting on that uniform, I have so much personal pride.”

About

Eilís Quinn is a journalist and manages Radio Canada International’s Eye on the Arctic circumpolar news project. At Eye on the Arctic, Eilís has produced documentary and multimedia series about climate change and the issues facing Indigenous peoples in the circumpolar world. Her documentary Bridging the Divide was a finalist at the 2012 Webby Awards. Eilís began reporting on the North in 2001.

Her work as a reporter in Canada and the United States, and as TV host for the Discovery/BBC Worldwide series Best in China, has taken her to some of the world’s coldest regions including the Tibetan mountains, Greenland and Alaska; along with the Arctic regions of Canada, Russia, Norway and Iceland.

Twitter : @Arctic_EQ

Email : Eilís Quinn