The community’s desire to protect the peninsula goes back to the 1970s, when Panarctic Oils, Ltd., a joint venture made up of energy companies like Imperial Oil, Gulf Canada Resources, and Mobil Oil Canada, began making natural gas discoveries in Canada’s Arctic archipelago.

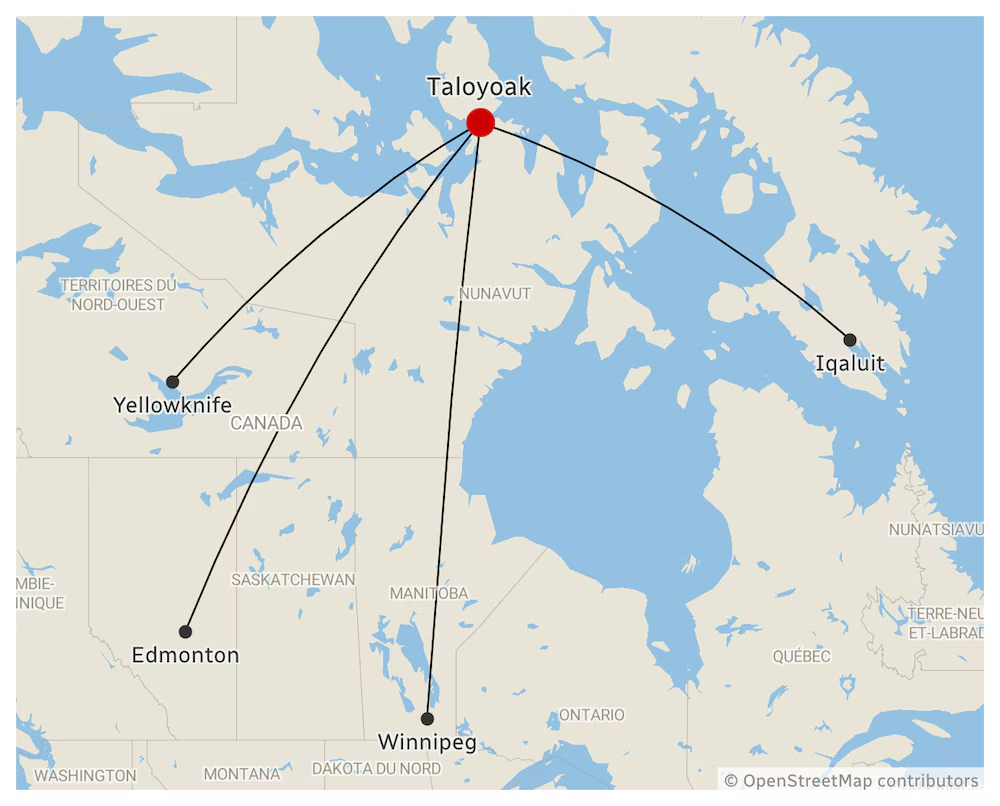

At that time, then Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Jean Chrétien said Panarctic’s finds warranted the study of pipeline routes from Cornwallis Island, approximately 400km north of the Boothia peninsula, to markets in southern Canada 2,000km away.

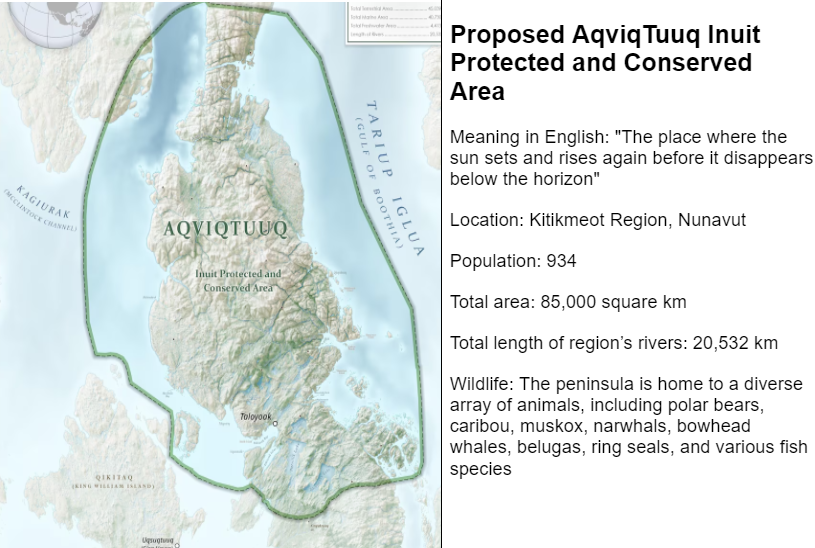

"The elders back then didn’t want anything like that near Aqviqtuuq", Ullikatalik said. "They knew, once the pipeline was there, it was going to disturb the ecosystem and the wildlife and potentially change it forever."