The first person from Japan to immigrate to Canada was Manzo Nagano (1855-1923). He arrived in the country in 1877. Nagano worked as a fisherman and labourer before becoming the owner of a hotel in Victoria, British Columbia.

A mountain was later named after him in the province.

The first wave of Japanese immigrants, called Issei (first generation), arrived in Canada between 1877 and 1928. Most of them settled in British Columbia. They were often poor and did not speak English very well. They worked the railways, in factories or as salmon fishermen on the Fraser River. Slowly, Canada began to limit Japanese immigration.

Japanese Canadians were denied the right to vote until the late 1940s.

22,000 Japanese placed in internment camps

During and after World War II, the federal government enacted policies that had a lasting impact on the Japanese-Canadian community in British Columbia.

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and Hong Kong, Ottawa invoked the War Measures Act to keep all Japanese-Canadians away from the Pacific coast. Some 22,000 Japanese-Canadians were sent to detention camps, farms or camps for prisoners of war. All their possessions, including their homes, their businesses and their personal assets, were sold.

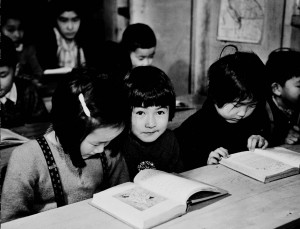

Many children grew up in these camps, including famous Japanese-Canadians like environmentalist and scientist David Suzuki and writer Joy Kogawa.

In British Columbia, the Japanese community was sent to a temporary camp on the grounds of Vancouver’s Pacific National Exhibition. They were then sent to camps in the interior of the province or to the neighbouring provinces of Alberta and Manitoba.

In the following decades, the Japanese-Canadian community sought compensation from the federal government. On 22 September 1988, over 40 years after the detention of Japanese in Canada , then- Prime Minister Brian Mulroney apologized to the survivors and their families . Ottawa offered $21,000 in compensation to each person affected.

From Slocan, British Columbia, to Lethbridge, Alberta

The Japanese placed in internment camps were used as cheap labor.

Men worked on road construction in northern British Columbia. Many families were also transported to work on beet farms in Alberta and Manitoba. Poorly housed, poorly clothed and malnourished, these workers lived in very difficult conditions.

Some camps were run by religious congregations.

At the end of the war, the Canadian government forced the Japanese to choose between deportation to Japan, a country many had never been to, or moving further east to the Prairies or the provinces of Ontario and Quebec.

In 1949, Canada allowed Japanese-Canadians who chose exile to return home to Canada if they had a sponsor. That same year, Japanese-Canadians reclaimed their citizenship rights, including the right to vote.