A picture of the Arctic Ocean at the 85th parallel north between the Russian archipelago of Franz Josef Land and the North Pole.

What’s at stake if risk assessments don’t evolve to reflect the reality of Arctic shipping?

(Andreas Kjol/Courtesy Norwegian Coastal Administration)

New guideline launched for Arctic-specific risk assessment in shipping

By Eilís Quinn

Web editor: Mathiew Leiser

A new Arctic-specific risk assessment tool for shipping has been released, something that the international experts behind it hope will become a building block for further knowledge sharing around maritime transportation in the North.

The Guideline for Arctic Marine Risk Assessment was put together by the Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response (EPPR) Working Group of the Arctic Council, an international forum made up of the world’s eight circumpolar nations: Canada, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, Russia and the United States; and the six Arctic Indigenous groups; the Aleut International Association, the Arctic Athabaskan Council, the Gwich’in Council International, the Inuit Circumpolar Council, the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North and the Sami Council.

“The Arctic isn’t like anywhere else, but not everybody knows that,” Jens Peter Holst-Andersen, chair of the EPPR told Eye on the Arctic in a phone interview from Denmark.

Jens Peter Holst-Andersen, chair of the EPPR

Extraordinarily until now, marine risk assessments have been largely based on generic risk factors from around the world. And although regimes like the International Maritime Organization’s Polar Code outlines things like shipping structure and equipment requirements for operating in the Arctic and Antarctic – little has been done internationally to understand how Arctic-specific risk factors should be considered for northern maritime operations, despite shipping ramping up across the Arctic because of climate change.

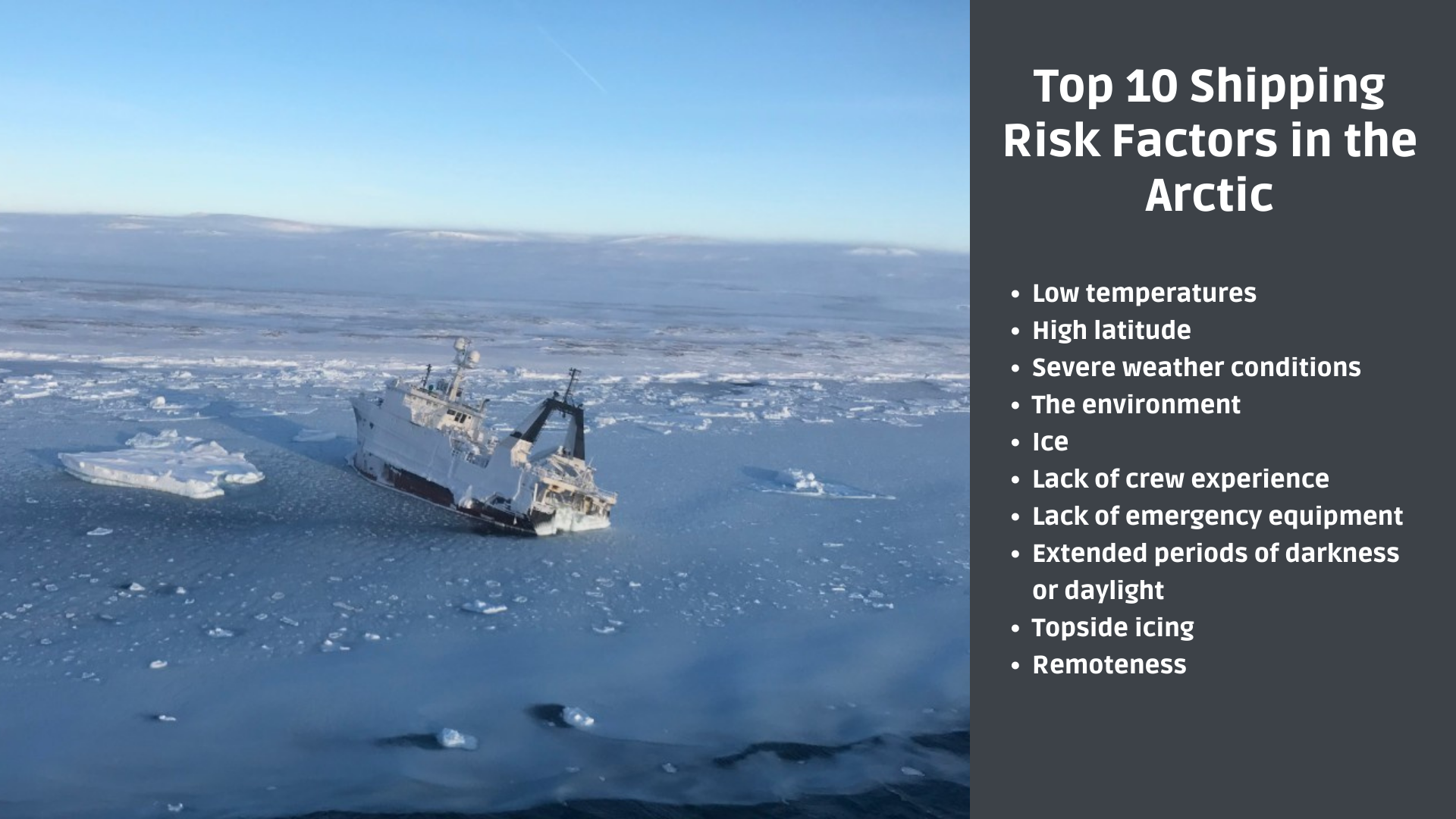

To do the work, the Arctic Council’s EPPR combed through international risk assessment tools, data and methodologies from around the world and developed a list of ten missing Arctic Risk Influencing Factors (ARIFs) that should be considered when assessing shipping risk in the North.

The Northguider fishing trawler capsized in the ice in the Strait of Hinlopen in the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard, Norway on March 17, 2019.

The trawler grounded here on December 28, 2018.

Data from the Arctic Council’s PAME Shipping Status Report #1 shows the number of ships in the Arctic has increased 25% from 1,298 in 2013 to 1,628 in 2019, and that 41% of those ships were fishing vessels.

(Governor of Svalbard/Courtesy Norwegian Coastal Administration)

“What’s important, is that when something goes wrong in the Arctic, the impact can be very different than if exactly the same thing happens somewhere else in the world,” Holst-Andersen said.

“If a ship runs aground further south, it’s often not a big issue, there’s lots of infrastructure nearby and help is often not far away. But if exactly same thing happens in the Arctic, it could become a big crisis because help can be many, many hours away and there’s no infrastructure.”

Understanding Arctic complexity

Dan Cowan, Manager with the Canadian Coast Guard’s Response Directorate and Chair of the EPPR’s Marine Environmental Response Expert Group, says the guideline will also help people better understand the complexity of responding to environmental accidents in the North.

“Think of an oil spill,” Cowan said in a phone interview. “If it happens in the Arctic at a certain time of the year, you may be dealing with it in 24-hour darkness, with any number of different ice conditions; pack ice, broken ice, there’s weather that could affect your equipment. The guideline we’ve put together ensures people are taking into account all those factors that may not otherwise be considered.”

Canadian Coast Guard Ship Henry Larsen near Gascoyne Inlet, in Canada’s eastern Arctic territory of Nunavut in 2011.

“Understanding the unique shipping risks in the Arctic is essential for informing risk mitigation strategies, and optimizing Coast Guard’s emergency preparedness and response strategies,” says Dan Cowan from the Canadian Coast Guard and the Arctic Council’s EPPR working group.

In Canada, Arctic shipping traffic is increasing each year, from 133 vessels in 2015, to 191 vessels in 2019, which included everything from cruise ships and general cargo vessels, to bulk carriers, pleasure crafts and tugs, according to data from the Canadian Coast Guard.

(Courtesy Canadian Coast Guard)

The project was the brainchild of the Norway’s Coastal Administration, a body in Norway responsible for emergency preparedness, maritime safety, radio navigation, vessel traffic and coastal management, and was financed by Norway’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Importance of Arctic collaboration

The guideline is free and available to anyone online. The tool walks users through six steps: Scope, context and criteria; and then risk identification, risk analysis, risk evaluation, risk treatment, and the report stage. It also provides links to data sets, web tools and best practices.

Cowan says the open data, shared experiences and transparency of the guideline are among its real strengths.

Dan Cowan.

(Courtesy Canadian Coast Guard)

The EPPR group stresses that although the guideline may be of interest to captains, it is not a voyage planner or compliance tool, but rather something that could be used by national to regional administrations, NGOs, inter-governmental organizations or consultants.

“It could be governments, it could be coast guards working on strategies for storing environmental response equipment caches,” Cowan said. “But really this for anyone that has to factor risk-assessment into their work.”

Holst-Andersen said response to the guideline so far has been enthusiastic, and there’s already been questions about whether the guideline could be expanded to include things like search and rescue references or social and cultural risks to Arctic communities.

“This is where we started, but if there’s enough interest going ahead, of course we can be open to develop the guideline even further.”

What is the Arctic Council?

The Arctic Council states’ and Permanent Participant organizations’ flags at the senior Arctic officials’ meeting in Ruka, Kuusamo, Finland in March 2019.

Experts say close collaboration between northern states on things like shipping can help better protect Arctic communities and the environment.

(Kaisa Siren/Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Finland)

Quick Facts

Year formed: 1996

Current Chair: Iceland

Arctic Council Members: Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Russia, United States

Permanent Participants: Aleut International Association, Arctic Athabaskan Council, Gwich’in Council International, Inuit Circumpolar Council, Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North, Saami Council

The Arctic Council was established in 1996 to work on sustainable development and environmental protection in the North.

The Arctic Council’s six working groups are made up of experts from around the world to examine issues ranging from environmental protection, to sustainable development, to emergency response in the Arctic.

The Guideline for Arctic Marine Risk Assessment can be consulted here

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: New “Frankenstein” shipping fuel could further pollute the Arctic, environmental groups say, Radio Canada International

Denmark: More shippers and shipping companies boycott Arctic sea routes, but it isn’t solving the problem, experts claim, The Independent Barents Observer

Finland: Finland investigates oil leak risks from Baltic Sea shipwrecks, Yle News

Greenland: The Arctic shipping route no one is talking about, Cryopolitics Blog

Iceland: Iceland to restrict heavy fuel oil use in territorial waters, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Hybrid-powered electric cruise ship navigates Northwest Passage, CBC News

Russia: Shipping figures rising on Russia’s Northern Sea Route, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: Carnival Corporation ships switch to cleaner fuel on Arctic cruises, Radio Canada International

About

Eilís Quinn is a journalist and manages Radio Canada International’s Eye on the Arctic circumpolar news project. At Eye on the Arctic, Eilís has produced documentary and multimedia series about climate change and the issues facing Indigenous peoples in the circumpolar world. Her documentary Bridging the Divide was a finalist at the 2012 Webby Awards. Eilís began reporting on the North in 2001.

Her work as a reporter in Canada and the United States, and as TV host for the Discovery/BBC Worldwide series Best in China, has taken her to some of the world’s coldest regions including the Tibetan mountains, Greenland and Alaska; along with the Arctic regions of Canada, Russia, Norway and Iceland.

Twitter : @Arctic_EQ

Email : Eilís Quinn