Clouds may be skewing Arctic warming predictions, says study

A new study is shedding light on why it’s so difficult to predict Arctic warming—and suggests that cloud formations might be a major reason.

“Our results explain why the wide inter-model spreads in projected future Arctic warming can be attributed to cloud bias,” the researchers said in the paper.

“Thus, these provide a better understanding of uncertain factors in atmosphere–ocean–cryosphere interactions.”

To conduct the study, published in the journal Ocean-Land-Atmosphere Research, a team from Okayama University in Japan analyzed 30 climate models and compared them to satellite and reanalysis data.

The team focused on Arctic winters—when there’s no sunlight—to isolate how clouds alone affect warming.

Once they crunched the data, they found is that many models are making the Arctic look colder than it really is, because they assume Arctic clouds contain more ice than liquid.

But as the Arctic warms, those clouds are increasing containing more liquid than before.

Small change, big consequences

And while it may seem like a small change, the researchers say it actually has big consequences.

Liquid clouds trap more heat near the surface than ice clouds.

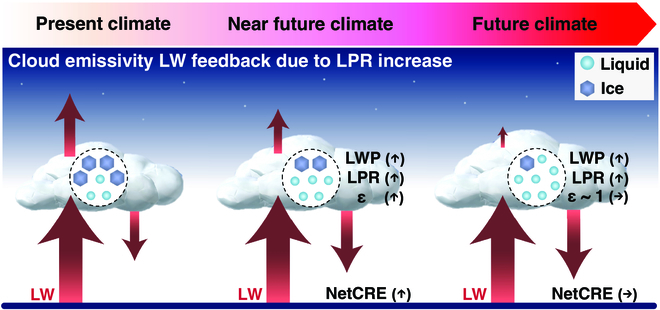

This effect, which the researchers call cloud emissivity feedback, occurs when warming shifts cloud composition from ice to liquid, increasing their ability to emit longwave radiation back to the surface. That, in turn, intensifies warming.

If models don’t reflect that, they could be underestimating just how fast the Arctic is warming, the team found.

“Our analyses of the future climate clearly revealed that the ice-to-liquid cloud phase transition in response to anthropogenic warming results in increased LW [longwave] cloud emissivity and strengthened surface cloud warming,” the paper said.

“This, in turn, enhances Arctic warming.”

The paper said this matters most in the Arctic winter, when sunlight isn’t around to warm the surface and clouds are the primary source of heat retention.

The researchers say errors in this kind of modeling can distort everything from sea ice loss projections to weather systems predictions to long-term climate outlooks.

The researchers say better representation of cloud properties in models could help reduce uncertainty in future Arctic climate forecasts—and help policymakers better prepare climate mitigation.

Comments, tips or story ideas? Contact Eilís at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Study examines physical, social costs of thawing permafrost across Arctic regions, CBC News

Norway: Svalbard glacier once survived a warmer climate, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Melting permafrost may release industrial pollutants at Arctic sites: study, Eye on the Arctic

United States: Trump’s cuts threaten US polar science after decades of data collection, Blog by Mia Bennett