China’s Arctic involvement ‘highly exaggerated,’ Harvard researchers say

China’s activities in the Arctic in recent years have been “highly exaggerated” due to “alarmist language in terms of scale, scope and risk,” according to research by Harvard University.

“It is apparent that most of this anxiety is about what might be, not what has actually happened,” researchers for the Belfer Center for science and international affairs at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard’s school of public policy.

Their paper, titled Cutting Through Narratives on Chinese Arctic Investments, was published in June. It was written by Arctic researchers Anders Christoffer Edstrøm from Norway, Guðbjörg Ríkey Th. Hauksdóttir from Iceland, and Whitney Lackenbauer of Trent University in Peterborough, Ont.

For years, China’s Arctic ambitions have faced international scrutiny.

In 2013, China was granted observer status at the Arctic Council, an intergovernmental organization of all eight Arctic nations: Canada, the United States, Russia, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Iceland and Sweden.

A few years later, in 2018, Beijing announced its Polar Silk Road strategy. It envisioned China’s deeper involvement in Arctic governance along with mineral and scientific exploration of the region.

Since then, China has proclaimed itself a “near-Arctic state” – despite not having any territory in the polar areas – and the country’s ambassador to Canada, Wang Di, told Nunatsiaq News last year that Arctic affairs should be a concern of a “global village.”

Since 2003, China is estimated to have invested more than $90 billion above the Arctic Circle, largely in energy and mineral sectors, according to the U.S. House of Representatives committee on foreign affairs estimates in 2022.

However, the Harvard researchers say that figure is “inflated” with unsuccessful investments and projects proposed but not implemented.

“Our research finds that these numbers are highly exaggerated and often mobilized to support a narrative in which China is successfully ‘buying up’ the Arctic region,” the paper said.

Of 57 Chinese investment projects that researchers list, 18 are active and only one is located in Canada. A majority of the projects have been either cancelled or are in question.

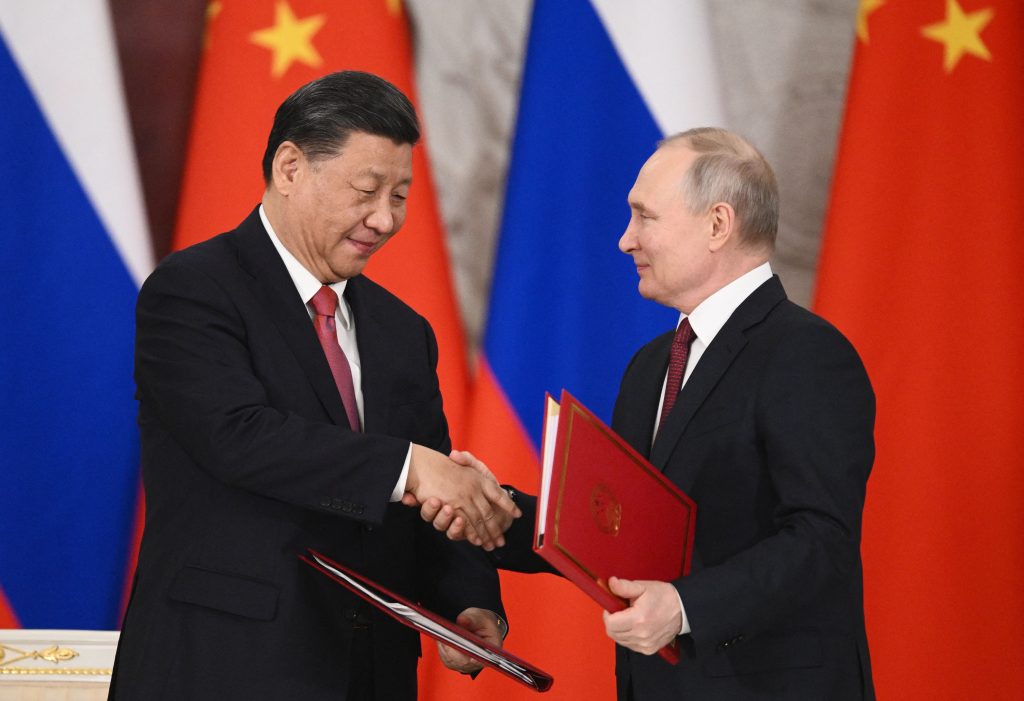

Of the eight Nordic member nations, only Russia has allowed a significant Chinese presence in its Arctic.

AFP via Getty Images)

In 2022, the two countries signed a joint statement proclaiming a relationship with “no limits” including joint oversight of traffic along the Northern Sea Route, 5,600-kilometre shipping passage along Russia’s Arctic coast line.

As well, the countries agreed on joint naval and coast guard exercises in the Bering Sea, and joint air patrols near the coast of Alaska.

But when it comes to Canada and the other six “like-minded” Arctic states, nearly all Chinese investment in the region has failed or stalled.

China’s footprint in Canada’s North only includes a Nunavik nickel mine owned by Jien Canada Mining Ltd. and two mineral development projects in the Yukon and the N.W.T. that have been “in stasis for many years.”

“China’s investment record in the Canadian North is not strong, and Chinese companies have also seen significant failures,” the researchers said.

One of those failures was in 2020, when Chinese state-owned Shandong Gold Mining Co. wanted to buy the Hope Bay gold mine complex, 150 kilometres southwest of Cambridge Bay, for $207.4 million.

The Canadian government rejected that deal after a national security review.

The Harvard researchers say that identifying investments that pose a security risk is a source of “debate and division.”

“Arctic states should continue to balance considerations of national interest connected to potential risk, potential economic benefits and societal support before deciding to allow, limit, or reject investments,” they wrote.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Lithium company exploring N.W.T. hopes to refine material in Canada, not China, CBC News

Finland: Finland hails plan for allies to join NATO land forces in North, The Independent Barents Observer

Iceland: Iceland’s FM announces defence review, calls revamped security policy ‘urgent’, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: China asked to remove stone lions from Arctic research station in Svalbard, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Significant progress in China-Russia talks on Arctic shipping: Kremlin, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Nordic-Baltic region joins forces around Sweden’s CV90, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: U.S. regulator eyes Arctic shipping chokehold as key deadline approaches, Eye on the Arctic