How a solar energy company is trying to lower Arctic communities’ diesel dependency

Green Sun Rising is based in Canada’s southernmost city, Windsor, but has 66 solar installations in the North

A solar energy company in Canada’s southernmost city says it is reducing carbon emissions in Canada’s north by nearly 1.3 million kilograms per year.

Green Sun Rising completed another four solar installations in Nunavut this summer – in Pond Inlet, Grise Fiord, Arctic Bay and Clyde River.

That brings its total number of installations across the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Nunavik and Labrador to 65; Green Sun also has a single installation in northern B.C.

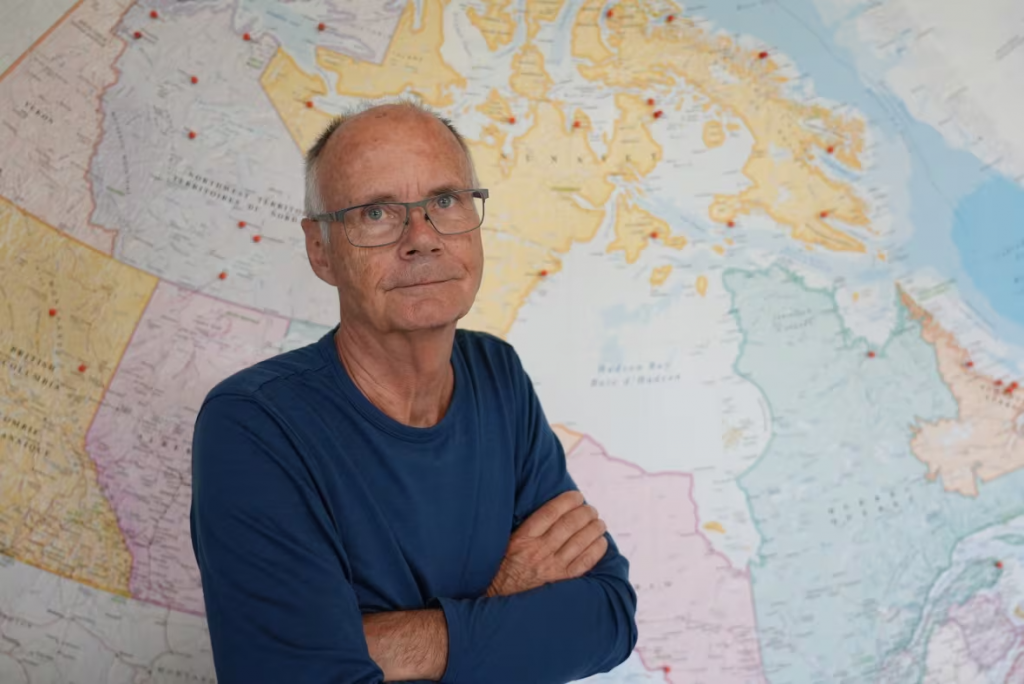

“The total of 66 solar systems we presently have in operation across the Canadian North … are avoiding over 500,000 litres of diesel every year,” said Klaus Dohring, the president of the Windsor-based company.

“And this is diesel in the community. I cannot quantify the energy required to bring the diesel to the community.… But I’m estimating that you can add easily 20 per cent to the cost for simply transportation and storage.”

The four new solar installations in Nunavut are connected to the Qulliq Energy Corporation’s Commercial and Institutional Power Producers Program, a program that allows government departments, hamlets and businesses to generate electricity using renewable energy systems and sell it to the utility.

Integrating solar vs. guarding against outages

Green Sun Rising also has a number of installations in Nunavut under QEC’s net metering program, which allows residential customers and one municipal customer per community to generate their own electricity from renewable energy sources and integrate it into the corporation’s grids.

In return, customers receive credits for any surplus power they deliver to the grid.

Other provinces and territories have similar programs.

But the growth of solar in the North is slowed by policies aimed at protecting energy grids from the inconsistent supply of power from renewable sources, Dohring said.

Diesel generators were not traditionally built to handle the kind of fluctuations in demand that come from having renewable energy sources go online and off-line as the weather changes, said Doug Prendergast, the manager of communications for the Northwest Territories Power Corporation.

“You end up with something called ‘generator cycling,'” he said.

“There … could be issues where the diesel generator couldn’t adapt as quickly as it would need to and … the result would likely be an outage.”

The N.W.T. Public Utilities Board currently caps the amount of third-party-generated renewable energy on the grid at 20 per cent.

Nunavut’s Qulliq Energy Corporation (QEC) has no formal cap because it has very few renewables on its grids, CEO Ernest Douglas said.

But both Dohring and the senior administrative officer of Grise Fiord said QEC has restricted the Green Sun Rising facility’s output in that community.

Building confidence in renewable energy

Dohring said grid stability is very important but also described QEC’s restriction as “super conservative.”

“The agreement with them is that they will use the next three years of runtime, operating time, and then overtime,” he said.

“As they gain more experience and confidence, we will revisit the limitation and then open it up.”

Douglas said any restriction on the output of the Green Sun project was likely put in place by one of QEC’s engineers based on the specifics of the project and grid.

Grise Fiord received a new diesel generator in 2019 that is capable of integrating renewables, according to the Canada Energy Regulator.

Prendergast said new technologies such as variable-speed diesel generators, which can better respond to the sudden changes in the output of renewable energy sources, are making it easier for utility companies to integrate renewables into their grids.

So, he said, are battery storage systems and microgrid controllers, which better coordinate the components of an energy grid.

In N.W.T., the minister responsible for the Public Utilities Board issued a directive to the board in April to increase the cap on renewable energy generation to at least 30 per cent of the average annual load demand.

Prendergast said the 20 per cent cap was put in place in 2014 when there was less knowledge about how renewables would operate in a northern climate, and the plan was always to revisit it once utilities had more experience with them.

“That’s really what has been happening, and we’ll see where it winds up,” he said.

Currently, nearly all of the electricity generated in Nunavut and the Nunavik region of Quebec comes from diesel fuel according to the Canada Energy Regulator and Natural Resources Canada.

Approximately a fifth of the energy generation in N.W.T. is also from diesel, according to the territorial government.

And there are 23 communities in Newfoundland and Labrador that are reliant on diesel generation, including 16 along the Labrador coast, NL Hydro says on its website.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Arctic energy, security on agenda as Western premiers meet in Yellowknife, CBC News

Norway: Will the green transition be the new economic motor in the Arctic?, Eye on the Arctic

Sweden: Sweden’s climate policies closer to reaching goals, Radio Sweden