Meeting Tom Smitheringale Again!

Tom Smitheringale Photo Gallery

I slept in this morning. After last night’s vodka and lard with the Ukrainians, I didn’t feel like waking up for an early breakfast – I was still feeling full all of those calories.

I showered, enjoying every bit of those fancy European shampoos, body lotions and soap that sat on the shelf of my room at the Thule Air Force base in Greenland.

I made myself a cup of coffee and tried one last time to call that mysterious number somewhere in Canada – I’m still not sure whether it’s in Trenton or Ottawa – to get booked on that C-17 flight that’s taking the U.S. ambassador and Tom Smitheringale to Ottawa. From there it’s just an hour-and-a-half drive to Montreal.

But no luck… There was no answer on the other end. I left a polite phone message, hoping that someone would call me back, but I knew deep in my heart that it was to no avail.

So it was off to Winnipeg; at least I would see the city. And if we got there early enough I might even get a flight to Montreal the same night!

I had time to check my email messages, catch up with a bit of work and then it was quarter to noon: time to pack up and meet the Hercules crew that would be taking me and Dave to Winnipeg.

We called in a minivan and piled all our belongings in for the short ride to the airport. The minivan pulled in right up to the Herc and we quickly loaded all our luggage and then went into the aircrew lounge to wait for the C-17 that was bringing the American ambassador and Tom here, to Thule. They would be heading to Ottawa after their short stopover.

Brief reunion with Tom Smitheringale

The C-17 landed quietly, carrying its bulk with the powerful grace of a super heavyweight boxer.

The C-17 landed quietly, carrying its bulk with the powerful grace of a super heavyweight boxer.

It taxied in right in front of the windows of the aircrew lounge and unlike in Alert, nobody even blinked when I stepped out onto the porch to snap a few pictures of the aircraft’s high-powered visitors.

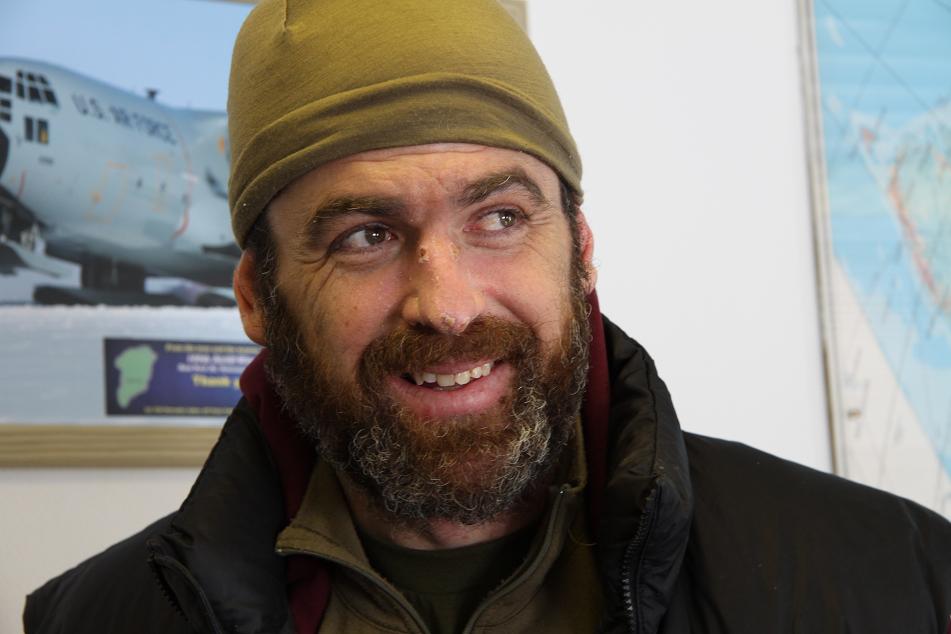

I immediately picked up Tom Smitheringale, towering at least a head over every other passengers, as he walked out gingerly and headed right towards me.

His gait seemed more sure and less painful and he appeared surprised and pleased to see me as he reached out his hand for a handshake.

I squeezed it ever so slightly, afraid of hurting his frostbitten fingertips. He looked more rested than just a day ago, but still somewhat dazed. On his first day in Alert he had seemed remarkably energetic for someone who had gone through such an ordeal and I realize now that he must have still been going on the Adrenalin rush of his rescue.

When we met him three days later, after returning from Ward Hunt Island, you could see that adrenaline rush was starting to wear off and the immense fatigue of 49 days battling the elements in the harshest environment on this planet were starting to set in.

Yet his recovery seemed almost miraculous. His face still bore the scars inflicted by the Arctic winter: frostbite marks on his nose and his cheeks, and of course the blackened tips of his fingers. But he seemed to have put on more weight since I last saw him (he confirmed that he had already gained 5kg during his stay in Alert). And his fingers didn’t seem as bad. Tom said he had regained some sensation and that he was optimistic that doctors would be able to save them all.

He spoke in a quiet voice, bordering on a mumble as if he almost forced the sound from his drained body, as we chatted and joked about the media circus waiting for him upon his arrival in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

He said he had already spoken with his mom, who’d be waiting for him in Ottawa along with an Australian TV crew. “I think I’m going to be grounded,” he said with a wide grin.

We sat at the aircrew lounge and Tom patiently answered questions from the Herc crew. They were part of the 435 Search and Rescue Squadron based in Winnipeg. They would have been the ones to go and look for him had it not been for Operation Nunalivut 10, which had placed a civilian helicopter and two Twin Otter planes at Alert and Ward Hunt Island plus at least five SAR techs (search and rescue technicians) who accompanied the Ranger patrols as medics for the duration of the exercise.

Maj. March Pettitt, commander of the Herc, calculated that in normal circumstances it would have taken them at least 10 to 11 hours to get to Tom’s location. Then they would have had to parachute two SAR techs, who would have cared for Tom until Canadian Forces were able to scramble one of the search and rescue helicopters stationed a thousand kilometres away, on Canada’s Atlantic coast, to pick them up from the ice pan. Even with the weather cooperating – and that is a big IF – it could have taken two or three days before they could extract Tom to safety. Who knows what would have been the extent of his frostbite injuries by then.

But with all those assets in place for the exercise, it took Canadian Forces only six hours from the moment Tom activated his distress signal to rescue him.

“That’s luck. That’s just ‘buy a lottery ticket’ kind of luck,” Maj. Pettitt summed up everybody’s feelings.

“That’s luck. That’s just ‘buy a lottery ticket’ kind of luck,” Maj. Pettitt summed up everybody’s feelings.