Laser technology used to map polar bear den habitat

What is the best way to find sites that could be used for polar bear dens, the cozy snow caves where sows give birth and nurture their newborn cubs?

On Alaska’s pancake-flat North Slope, it may be deployment of laser-guided topography mapping, a new study says.

Airborne light detecting and ranging — commonly known as LiDAR — proved extremely accurate at finding suitable denning sites on the North Slope, according to the study, which was led by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Alaska Science Center.

LiDAR employs laser imaging to collect detailed information about the river banks, coastal bluffs and other small bumps and depressions that collect snow blown over the otherwise-flat landscape. Polar bears need substantial snow depths to create dens, and snow cover on flat tundra is too sparse unless it accumulates into sizeable drifts.

The scientists, who presented their findings in a poster at the American Geophysical Union fall meeting in San Francisco last week, evaluated data collected through LiDAR surveillance over 540 square miles of the central North Slope. They compared LiDAR data — acquired in 2006 from laser streams shot from aircraft — to data from radar and airborne photography methods. Then they matched the surveys to maps of known polar bear dens. The LiDAR data proved superior, nearly perfect at pinpointing suitable sites that polar bears select in midwinter for denning, according to the scientists’ review.

Importance of identifying denning habitat

The LiDAR survey area runs from the giant Prudhoe Bay oil field in the west to the developing Point Thomson oil and gas field in the east. With oil development spreading along the coastline and more industry interactions with polar bears looming, it is important to identify denning habitat early on, the study says.

A key advantage to LiDAR technology is the fine-grain images it produces, with details down to a square meter or two, said George Durner, a USGS research zoologist who participated in the study. That compares to interferometric synthetic aperture radar technology, known as ifSAR, which gets details down to about the 5-square-meter level, said Durner, who did a previous study using ifSAR to identify polar bear dens in the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska. That study was published in the June issue of the journal Arctic.

As a tool to protect polar bears, currently listed as a threatened species, LiDAR is “wonderful,” Durner said. “I really like it. The more LiDAR data we have, the better we can protect polar bear denning habitat.”

Industry use

Oil companies and scientists working on the North Slope regularly use thermal imaging technology to find places where mother bears and their cubs are nestled in dens, letting industrial users know which sites to avoid during that denning season. But future LiDAR surveys could identify potential denning sites long before the bears settle on them.

Den sites of the past may not be the same as those in the future, thanks to the Arctic’s warming climate. Permafrost thaws are creating new depressions on the tundra surface, and advancing erosion is moving river banks and coastlines.

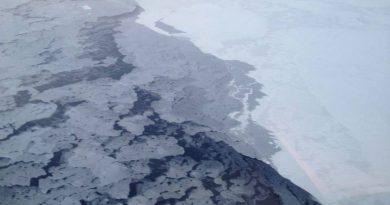

Climate change has already brought more denning bears on land, away from the sea ice, past studies have found. Western Beaufort Sea polar bears once preferred denning on thick, multiyear sea ice, which provided a stable platform and lots of textured features to collect deep snow. But multiyear ice is dwindling and expected to diminish further. Now Beaufort Sea polar bears are opting for land den sites, according to USGS research. From 1985 to 1994, 62 percent of the Western Beaufort Sea dens were on pack ice, but that dropped to 37 percent for the period from 1998 to 2004, according to a study by USGS biologists that was published in 2007 in the journal Polar Biology.

Contact Yereth Rosen at yereth(at)alaskadispatch.com