First Nations groups want fixes to Canadian gov’s draft child welfare law

A draft of the federal Liberal government’s proposed Indigenous child welfare bill recently received negative reviews from First Nations representatives involved in co-development talks with Ottawa, according to a grand chief.

Ottawa announced last November it would table the bill that would break from more than 100 years of destructive federal policies aimed at Indigenous children that began with residential schools and led to tens of thousands of Indigenous children in care today.

The promised legislation is an outgrowth of the 2016 Canadian Human Rights Tribunal ruling that found Ottawa discriminated against First Nations children by underfunding child welfare services on reserve.

Cindy Blackstock, who heads the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society and led the human rights complaint, has been in the loop on the draft legislation as a result of the tribunal ruling.

Blackstock said legislation must include an equitable and statutory funding base, affirm First Nations jurisdiction, focus on structural flaws that put children at risk, family and community health and acknowledge the “sacredness of children.”

“Absent these critical ingredients, the law risks being a paper tiger and a disappointment to another generation of children,” said Blackstock in an emailed statement.

Federal officials presented the draft version of the bill late last month to First Nations representatives from an Assembly of First Nations working group created to lead co-development work.

Concerns over funding and jurisdiction

“There were some good things and some things we had concerns about,” said Association of Iroquois and Allied Indians (AIAI) Grand Chief Joel Abram, the Ontario First Nations political representative on the working group.

Abram said his organization would oppose the proposed legislation if problems aren’t fixed in the final product.

AIAI previously opposed the now-shelved Indigenous rights and recognition framework which aimed to enshrine the Constitution’s section 35 Aboriginal rights in federal legislation on grounds it threatened First Nations rights.

“We were one of the main opponents pushing against the framework and if this bill isn’t right, we will do the same thing,” said Abram, who saw the draft but couldn’t discuss details due to a confidentiality undertaking.

Abram said his organization’s main concerns going into discussions on the bill — that it recognize First Nations jurisdiction over child welfare and enshrine equitable and statutory funding — remained following his review of the draft bill.

He said federal officials were told which parts of the draft remain problematic and how they could be fixed.

“The best we could do at that time was to raise concerns in specific areas and suggest what would work,” he said.

‘A work in progress’

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told the AFN chiefs in December the bill would be tabled by the last week of January, but federal officials are still working to finalize it.

Indigenous Services Seamus O’Regan said in an emailed statement that the concerns raised by First Nations representatives did not fall on deaf ears.

“We must ensure that critical feedback from our partners is incorporated,” said O’Regan in the statement.

“We have heard clearly from First Nations, Inuit and Métis through engagement and the co-development process that essential elements must be addressed.”

O’Regan said in the statement that the legislation would be tabled “shortly” and that it was “important … we get it right.”

AFN Manitoba regional Chief Kevin Hart, who chairs the legislative working group, said discussions continue with federal officials on improving the proposed legislation.

“We are going back and forth,” said Hart. “It is still a work in progress.”

Time is running out on the Liberal government which faces 13 sitting weeks in the House of Commons calendar before dissolution and the beginning of the next federal election period.

The Indigenous child welfare bill is one of three major pieces of legislation promised by the Trudeau government to Indigenous Peoples, including a bill on Indigenous languages and the rights framework.

Only the Indigenous Languages Act has made the House of Commons order paper.

Jane Philpott, the former minister of Indigenous Services, announced the government’s intention to table Indigenous child welfare legislation last November.

Philpott, who is now Treasury Board President, said at the time the legislation would “enable” First Nations jurisdiction over child welfare which has been the domain of the provinces.

The Indian Act, which governs the majority of First Nations, makes no mention of child welfare.

Philpott said the legislation would mark a “turning point” in addressing a “humanitarian crisis” created by the disproportionate number of Indigenous children in foster care.

Hope remains bill will hit the mark

AFN National Chief Perry Bellegarde has said there are an estimated 40,000 First Nations children in care.

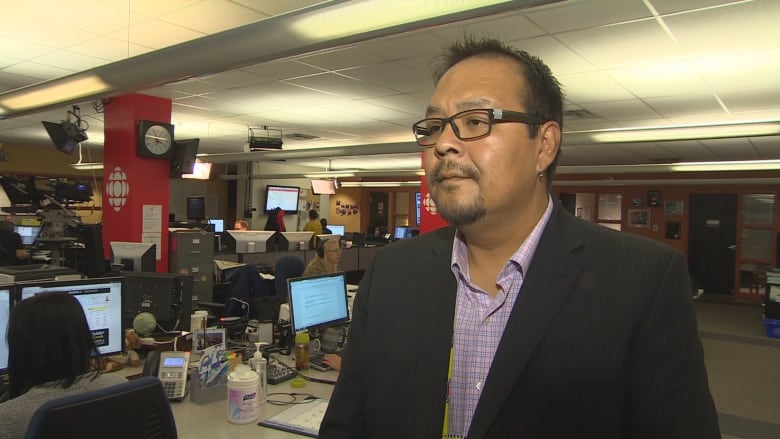

Mary Teegee, a technical advisor on the AFN legislative working group, also saw the draft bill and said it contained flaws.

“It definitely wasn’t what we had expected,” said Teegee.

“I think there is a lot of work to be done. There was an opportunity for people to provide their input as to what should be included, what should be changed and what should be strengthened.”

Teegee, executive director of Carrier Sekani Family Services in B.C., said the legislation must reflect what First Nations demand: jurisdiction.

She said it should also guarantee the statutory and equitable funding required under the Human Rights Tribunal ruling.

“We have done so much work. Our blood, sweat and tears are in it,” said Mary Teegee, who was a board member of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society when it launched the human rights complaint in 2007.

“Hopefully, something good will come out of it and we will develop our laws in our communities,” she said.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Inuit, Sami leading the way in Indigenous self-determination, study says, CBC News

Finland: One in 10 Finnish families with young children dealing with food insecurity: survey, Yle News

Sweden: Calls for more Indigenous protection in Sweden on Sami national day, Radio Sweden

United States: Alaska and its tribes sign child services agreement, Alaska Public Media