Why southern Canadians should brush up on their geography of the northern territories

A large national non-profit wrote CBC North last week promoting two new historic places in the Northwest Territories. Problem is — they’re in Yukon, west of the N.W.T.

This kind of flub is nothing new to northerners. Canadians’ ignorance of the three territories has become something of a joke. Remember when Travel Alberta forgot Nunavut? CBC has goofed too — just this year writers (not in the North) have placed Iqaluit in the N.W.T. (it’s in Nunavut, in Canada’s eastern Arctic), and referred to the Nunavut government as “provincial” (it’s territorial). The satirical site, The Beaverton, summed up this national knowledge gap aptly in a headline a few years ago: “Whitehorse changes name to ‘Yellowknife’ to avoid confusion.”

Ken Coates followed a career path that aimed to change that. Growing up in Whitehorse, in northwestern Canada, he was riled up that the territories were entirely omitted from his textbooks.

“I’m not an angry person, but I was when I was going through my studies,” he said.

Coates is a Canada Research Chair in regional innovation based at the University of Saskatchewan, and a specialist in northern history, northern development and Indigenous rights.

He says Canadians go through periods when they’re excited about the North, but then go back to ignoring it.

“I think Canadians like to view the North as a sort of an attic — sort of a place where you hide the treasures but don’t ever go up and look and see what they are,” he said.

Coates believes that southerners also feel guilty about the North, both in the territories and in the northern regions of the provinces.

“The general poverty of the Indigenous people in the North is a national disgrace. We haven’t been able to solve it.”

Do Canadians hate winter?

Coates thinks Canadians are more out of touch with the territories than ever before. Though Yukon, Nunavut and the Northwest Territories are often lumped together, they are each distinct — geographically, culturally and demographically.

“You end up with people sort of lumping it all together and then attaching two or three pictures to it,” Coates said. “And the pictures are usually of a polar bear on an ice floe and then a very poor Inuit community.”

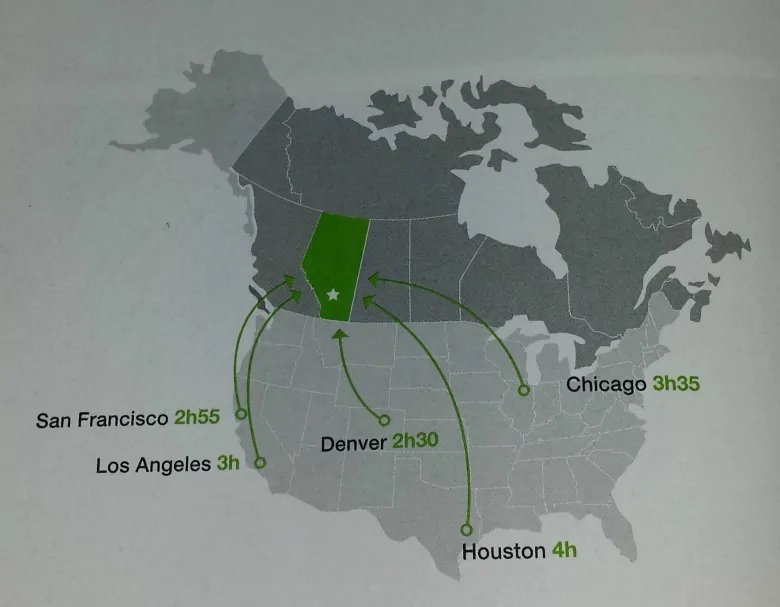

He also points out that years ago, many more people from the South visited family members who lived and worked in the North. But now, with fly-in/fly-out jobs in mines and construction, it’s mostly Japanese and Chinese tourists who are heading north to take in the aurora borealis.

“We’ve created this sort of distance from the North where it’s almost like talking about the moon when you talk to southerners about the realities of the Canadian North.”

Ken Coates, Canada Research Chair

According to Statistics Canada, of the 328,454,000 domestic trips made by Canadians in 2017, only 0.03 per cent, or 106,000 people, travelled to or within the three territories.

By comparison, Coates points to how many Canadian snowbirds travel south to warm climates, like Florida and Mexico.

“Our idea of winter in Canada is actually huddling down in a well-heated mall in a southern city,” he said.

“We don’t embrace winter anywhere near as much as we should. And I find that really kind of sad and almost tragic.”

He notes that Americans flock to Anchorage and Fairbanks, Alaska, and the same goes for northern Scandinavian destinations, where cottages are often designed for winter, and residents are excited to be winter tourists in their own country.

“We don’t study winter, we don’t really understand the impact of winter on our lifestyle, we take it as a sort of a necessary evil.”

Rebecca Alty, Yellowknife’s mayor who grew up in the Northwest Territories’ capital, hears a lot of misconceptions when representing her city in the South.

“It’s very common,” she said. She allows that Yellowknife and Yukon both starting with a Y might be a source of confusion, but calls it “unfortunate that Canadians mix up that geography so much.”

Alty says people have asked her if she knows someone in Whitehorse, which she likens to asking an Albertan if they know someone in Saskatchewan.

“I don’t know if there’s anything we could do as a nation to get better at remembering the three territories, but it would be great if we could.”

Why the territories matter

Coates says meaningful investment in the territories could have a big impact. He points to the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and the University of Tromsø in Norway, as examples.

When Norway chose to put its second medical school in the north, the results were “unbelievable,” Coates says.

Now, there is no shortage of doctors or nurses in northern Norway and medical services are fine — a stark difference from the Canadian North. Fairbanks was a small town when the university was built, but it’s been a huge part of that community now for more than a century.

Coates says there is good reason for the rest of Canada to look to the territories: they’re the source of some of the “most innovative public policy in Canada;” they’ve made progress in figuring out how to capitalize on resources; and efforts to resolve Indigenous relations and toward cultural revitalization have also been more successful than in the South.

He calls it “our collective responsibility” to understand the territories. “I think we’re failing in that regard.”

“If you want to see Canada’s future, in many ways take a look to the North,” Coates said.

“Not because it’s going to produce wealth for the country as a whole, but because it’s producing viable solutions of local populations that wanted stability, they want shared prosperity, and they want shared opportunity, and so we should pay attention to that.”

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: ‘We’re up here!’ says Nunavut premier as Arctic Canadian territory celebrates 20th anniversary, CBC News

Sweden: Social Democrats lose Arctic stronghold over healthcare in Sweden’s regional elections, Radio Sweden

United States: Alaska’s largest airport expects more passengers this summer, Alaska Public Media