Biosecurity an increasing concern in Arctic, Antarctic regions, experts warn

As the climate warms, biosecurity issues will become an increasing concern for the polar regions says Kevin Hughes, a researcher at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and lead author of a recent paper on invasive species threats to the Antarctic Peninsula.

“No matter where you are, whether we’re talking about the Arctic or the Antarctic, you must reinforce biosecurity practices once you get to the polar regions,” Hughes said in a phone interview with Eye on the Arctic.

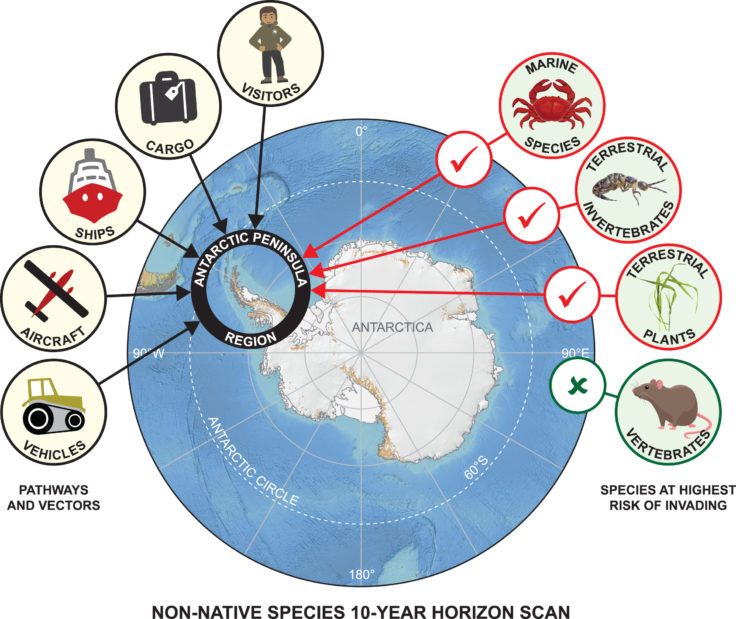

In the paper, “Invasive non‐native species likely to threaten biodiversity and ecosystems in the Antarctic Peninsula region” published the journal Global Change Biology this month, the authors identified the species most likely to cause the highest risk to biodiversity in the Antarctic Peninsula Region, a term that refers to the Antarctic Peninsula, South Shetland Islands and South Orkney Islands.

To do the study, the authors examined academic papers, reports and databases to pinpoint the most likely invasive species to set up in the region.

The names of the 13 species identified in the new study:

| 1 | Mytilus chilensis | Chilean mussel | Marine invertebrate |

| 2 | Mytilus edulis | Common blue mussel | Marine invertebrate |

| 3 | Protaphorura fimata | Springtail | Terrestrial invertebrate |

| 4 | Nanorchestes antarcticus | Mite | Terrestrial invertebrate |

| 5 | Halicarcinus planatus | Flattened crab | Marine invertebrate |

| 6 | Ciona intestinalis | Sea vase | Marine invertebrate |

| 7 | Leptinella scariosa | A buttonweed | Terrestrial plant |

| 8 | Botryllus schlosseri | Colonial Ascidian | Marine invertebrate |

| 9 | Carcinus maenas | European shore crab | Marine invertebrate |

| 10 | Undaria pinnatifida | Asian kelp | Marine algae |

| 11 | Leptinella plumosa | A buttonweed | Terrestrial plant |

| 12 | Chaetopterus variopedatus | Parchment worm | Marine invertebrate |

| 13 | Mytilus galloprovincialis | Mediterranean mussel | Marine invertebrate |

Source: British Antarctic Survey & “Invasive non‐native species likely to threaten biodiversity and ecosystems in the Antarctic Peninsula region” published the journal Global Change Biology

“Marine invertebrates such as mussels and crabs are top of the list of species considered most likely to invade the Antarctic Peninsula region, but flowering plants such as button weeds (e.g. Leptinella scariosa) and mites and springtails were also identified,” said David Barnes, a co-author of the study, in a news release this month.

“We know mussels can survive in polar waters, and can spread easily. When they establish they can dominate life by smothering the native marine animals that live on the seabed.”

Increased human activity in polar regions

Hughes says everything from tourism to increasing scientific activity in the region ups the risk.

“The Antarctica Peninsula region is by far the busiest and most visited part of Antarctica due to growing tourism and scientific research activities,” he said.

“Non-native species can be transported to Antarctica by many different means. Visitors can carry seeds and non-sterile soil attached to their clothing and footwear. Imported cargo, vehicles and fresh food supplies can hide species, including insects, plants and even rats and mice. Marine species present a particular problem as they can be transported to Antarctica attached to ship hulls. They can be very difficult to remove once established.”

Hughes says the BAS has already implemented strict measures to prevent transport of invasive species to their installations in Antarctica which include inspecting cargo before it leaves, something that includes bringing in a detection dog trained to sniff out rodents, and then another inspection upon arrival.

“We just don’t know what’s going to happen”

Hughes says more precautions needed to be taken worldwide as increased activity in the polar regions is accompanied by global environmental change.

“Australia and New Zealand are world experts when it comes to best biosecurity practices so there are good models. But once climate change kicks in, that changes everything, because once invasive species become established, it makes it increasingly difficult to get rid of.

“And with climate change, we just don’t know what’s going to happen, so that’s the scary part. We’re not prepared for what the consequences may be.”

Write to Eilís Quinn at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Invasive species – Fisheries and Oceans Canada has no mandate in Arctic, CBC News

Finland: Invasive “moss animal” gains foothold in parts of Finland, Yle News

Sweden: Sharp-edged mussel invades southern Sweden, Radio Sweden

United States: Communities wrestle with shark-bite mystery off Alaskan coast, Eye on the Arctic