Blog – 2021: Future doesn’t just happen – It’s what we make it

As I started work on this post, on December 23rd the thermometer here in north-western Germany showed 14° Celsius. I’ve long given up dreaming of a White Christmas in this part of the world, but roses and honeysuckle in bloom in mid-winter?

2020 marked the close of the warmest decade (2011-2020) on record, according to the World Meteorological Organization. As we head into 2021, a year when the world’s hopes of better times have arguably never been higher after the crippling and terrifying COVID-19 pandemic, the climate outlook is unlikely to bring any relief. The Met Office annual global temperature forecast for 2021 suggests that next year will once again enter the series of the Earth’s hottest years.

“Earth plays it cool, but global warming is unrelenting.” @metoffice annual global temperature forecast suggests that 2021 will once again enter the series of the hottest years on record, despite #LaNiña#ClimateChange #ClimateActionhttps://t.co/sKMnaQC7nn pic.twitter.com/XXPWe6qmn4

— World Meteorological Organization (@WMO) December 21, 2020

« Since the 1980s each decade has been warmer than the previous one. And that trend is expected to continue because of record levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide, in particular, remains in the atmosphere for many decades, thus committing the planet to future warming », the WMO wrote in its Provisional Report on the State of the Global Climate in December 2020.

We have just had the warmest decade (2011-2020) on record. This year is on track to be one of the 3 warmest on record, and may even rival 2016 as the warmest on record. The 6 warmest years have all been since 2015.#ClimateChange https://t.co/6OuUDnsC8W pic.twitter.com/ge9FGIvD2y

— World Meteorological Organization (@WMO) December 29, 2020

The average global temperature over the year was about 1.2 °C above the pre-industrial (1850-1900) level. Bearing in mind the upper limit set by the Paris Agreement to avert disastrous climate impacts is just 1.5°C, that is anything but reassuring.

The end of the Arctic as we know it?

More than 90% of the excess energy accumulating in the climate system goes into the ocean. Ocean heat is at record levels and more than 80% of the global ocean experienced a marine heatwave at some time in 2020. One of those extreme marine heatwaves happened in the Laptev Sea, a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, and lasted from June to October. Throughout the spring, summer and autumn, the sea ice extent was unusually low in the region, regarded as the « sea ice nursery ». Since the mid-1980s, the Arctic has warmed at least twice as fast as the global average, reinforcing a long downward trend in summer Arctic sea ice extent which has repercussions on the climate in mid-latitude regions.

Standardized daily #Arctic sea ice extent anomalies from 1 January 1979 through nearly the end of 2020…

Data from the consistent passive microwave satellite record. pic.twitter.com/lvo33K2eDg

— Zack Labe (@ZLabe) December 28, 2020

When the Arctic sea-ice reached its annual minimum in September, it was the second lowest in the 42-year-old satellite record. For July and October 2020, it was the lowest.

(See also: “When the Arctic ice won’t freeze”)

In the Siberian Arctic, temperatures were more than 5 °C above average, and the highest known temperature anywhere north of the Arctic Circle was registered in late June, when it reached 38.0 °C at Verkhoyans. This fuelled the most active wildfire season in an 18-year long data record, as estimated in terms of CO2 emissions released from fires, said WMO Secretary-General Taalas.

The annual Arctic Report Card published by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) had this message in 2020: « The sustained transformation to a warmer, less frozen and biologically changed Arctic remains clear ».

The way ahead

So how are the nations of the world doing when it comes to halting the emissions that are heating up the Earth like a hothouse?

The latest figures from the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC), Berlin say the budget for keeping climate warming below 1,5°C will be used up in 2027, the budget for 2°C in 2045. Their estimates and “budget countdown” are based on the IPCC Special Report Global Warming of 1,5°C in 2018.

Every year, the United Nations Environment Programme UNEP’s Emissions Gap Report assesses « the gap between anticipated emissions and levels consistent with the Paris Agreement goals of limiting global warming this century to well below 2°C and pursuing 1.5°. »

« Are we on track to bridging the gap? Absolutely not », says UNEP.

This year’s Emissions Gap Report finds that, “despite a dip in 2020 carbon dioxide emissions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the world is still heading for a temperature rise in excess of 3°C this century – far beyond the Paris Agreement goals of limiting global warming to well below 2°C and pursuing 1.5°C”.

« Wildfires, storms and droughts continue to wreak havoc », said Inger Andersen, UNEP’s Executive Director.

Despite the COVID-19 lockdown, atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases continued to rise, committing the planet to further warming for many generations to come because of the long lifetime of CO2 in the atmosphere.

Utopia or nightmare?

December 2020 saw the fifth anniversary of the signing of the Paris Agreement. Marking the anniversary in the German weekly DIE ZEIT on 10.12.20, Petra Pinzler and Bernd Ulrich write that for average temperature rise to stay below 1,5 degrees – leaving us now with only 0.3 degrees to go – countries would have to reduce their CO2 emissions five times as fast as they are planning.

They also note that we are already feeling the impact of the 1.2 degree rise, with forest fires, droughts – and forests dying off even in temperate Germany. Yet, they comment, this is in line with the Paris Agreement « plan », the amount of warming we are prepared to allow, the optimal goal we have reluctantly defined.

The problem, according to the two authors, is that the Paris Agreement made a 1.5 degree scenario look like a « positive utopia ». Seen from today’s standpoint, in a 1.2 degree world already experiencing severe impacts, 1.5 can only mean things will get worse, with more droughts, ice melt, biodiversity loss, extreme weather. The utopia turns into a nightmare.

At the same time, when it comes to politics, they write, 1.5 has come to represent a « radical » demand, which could only be made by e.g. naive, idealistic Fridays for Future youngsters. In our « new normal » 1.2 degree warmer world, a 2 degree target looks bold, 1.5 radical, they conclude.

Bridging gaps

So how do we get from here to the action necessary to speed up emissions reductions: to bring about the energy transition by mid-century, the carbon-neutral economy and society that could stop our planet from tipping into a realm of unpredictable climate chaos?

The pandemic which has upturned our lifestyles and brought economies to a standstill in 2020 could provide a key – and mark a turning point.

The climate crisis, over-exploitation of nature and the growing risk of pandemics are all related – and measures to help tackle one are likely to help with them all.

As Pinzler and Ulrich put it – these three crises needn’t add up, they can be solved « in synergy ».

Covid, climate – out of the crises

As a result of reduced travel, lower industrial activity and lower electricity generation because of the pandemic, carbon dioxide emissions are estimated to have fallen by around 7 per cent in 2020.

However, « this dip only translates to a 0.01°C reduction of global warming by 2050 », UNEP concludes. « Meanwhile, NDCs (national determined contributions, countries’ pledges for emissions reductions) remain inadequate. »

In view of the unusual circumstances, the 2020 UNEP Emissions Gap Report does not keep to its usual approach of considering only consolidated data from previous years as the basis for assessment: « To maximize its policy relevance, preliminary assessments of the implications of the pandemic and associated rescue and recovery measures are included throughout the report ».

The experts say recovery from the economic impacts of the pandemic could play a role in bringing about the transition to a zero-carbon economy.

According to the International Monetary Fund, the current global recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic « presents opportunities to set the economy on a greener path in order to boost investment in green and resilient public infrastructure, thus supporting GDP and employment during the recovery phase. »

As the UN Environment body puts it: « the unprecedented scale of COVID-19 economic recovery measures presents the opening for a low-carbon transition that creates the structural changes required for sustained emissions reductions. Seizing this opening will be critical to bridging the emissions gap ».

The UN experts say a low-carbon pandemic recovery could cut 25 per cent off the greenhouse emissions expected in 2030, (based on policies in place before COVID-19) and at least put the world close to the 2°C pathway.

That could significantly alter the figures brought to the table when COP26 – cancelled because of the corona crisis – is reconvened in Glasgow at the end of 2021.

Political progress

In my blog post at the beginning of 2020, I wrote:

« We would need to see some big changes in the USA, in a key election year, in Brazil, in China and India, to halt global warming in a hurry ».

At least two of those countries – and the globe’s biggest emitters to boot – have indeed seen key developments on the climate front over the past year.

(See also: The Arctic, the climate: some gloom but no doom – and a promise of progress)

The election of Joe Biden to replace Donald Trump as President of the USA is perhaps the biggest reason for optimism on the climate front. Biden faces a tall order with expectations that his actions could be decisive in keeping the world to the 1.5°C target. But his election will ensure that the world’s second-biggest emitter of greenhouse gases will come back into the Paris Agreement, and the green transition – which is already happening at state level in some parts of the USA – will be able to move forward and spread.

Xi Jinping, the President of China, the world’s biggest emitter, announced new climate targets during his Sept. 22 address to the U.N. General Assembly, including the nation’s plan to achieve carbon neutrality before 2060. It remains to be seen how the country’s continued promotion of fossil fuel projects at home and abroad will fit in with that, but China’s targets are key to achieving the world’s climate goals.

UNEP sees the growing number of countries that have committed to achieving net-zero emissions goals by around mid-century as the most significant and encouraging development in terms of climate policy in 2020. The proof of the pudding, of course, will be how – and how fast – they are turned into policy and action.

It’s up to us

But it’s not just up to the governments of the world. We in the prosperous, industrialised consumer-driven regions of the world, will have to change our lifestyles if the world is to get anywhere near carbon-neutrality by the middle of the century. UNEP calculates that around two thirds of global emissions are linked to private household activities. That means we also have to change at the individual level.

« COVID-19 has provided insight into how rapid lifestyle changes can be brought about by governments (who must create conditions that make lifestyle changes possible), civil society actors (who must encourage positive social norms and a sense of collective agency for lifestyle changes) and infrastructure (which must support behaviour changes). The lockdown period in many countries may be long enough to establish new, lasting routines if supported by longer-term measures. In planning the recovery from COVID-19, governments have an opportunity to catalyse low-carbon lifestyle changes by disrupting entrenched practices », says UNEP.

Sounds drastic – and this is from a UN body. I’m not sure how long that lockdown period would have to be and how society would cope with it – but disrupting entrenched practices to catalyse a low-carbon lifestyle could well be what we need.

« We have never seen the degree of awareness around environmental matters similar to what we’re seeing now », was what UNEP chief Inger Andersen said to me in an interview not long after she was appointed in 2019. She also stressed “the solutions are there”.

That was before the COVID19 crisis. Since then that awareness has been heightened further.

More and more people in the polluting, industrialised world, are thinking about how they live, eat and move.

Here in Germany, there is a huge ongoing debate about the problems of intensive farming. Eating less meat is becoming common. Organic products are becoming mainstream. Campaigns are growing to cut pesticides and protect bees and biodiversity. Even our small local community has its own tree-planting programme. Bike sales have rocketed. We have more cycling lanes in the making. Government incentives have boosted sales of electric cars. Renewable energy has become affordable. Carbon pricing is starting to have an impact. More and more organisations are divesting from fossil fuels. Plastic and packaging are perceived as problematic.

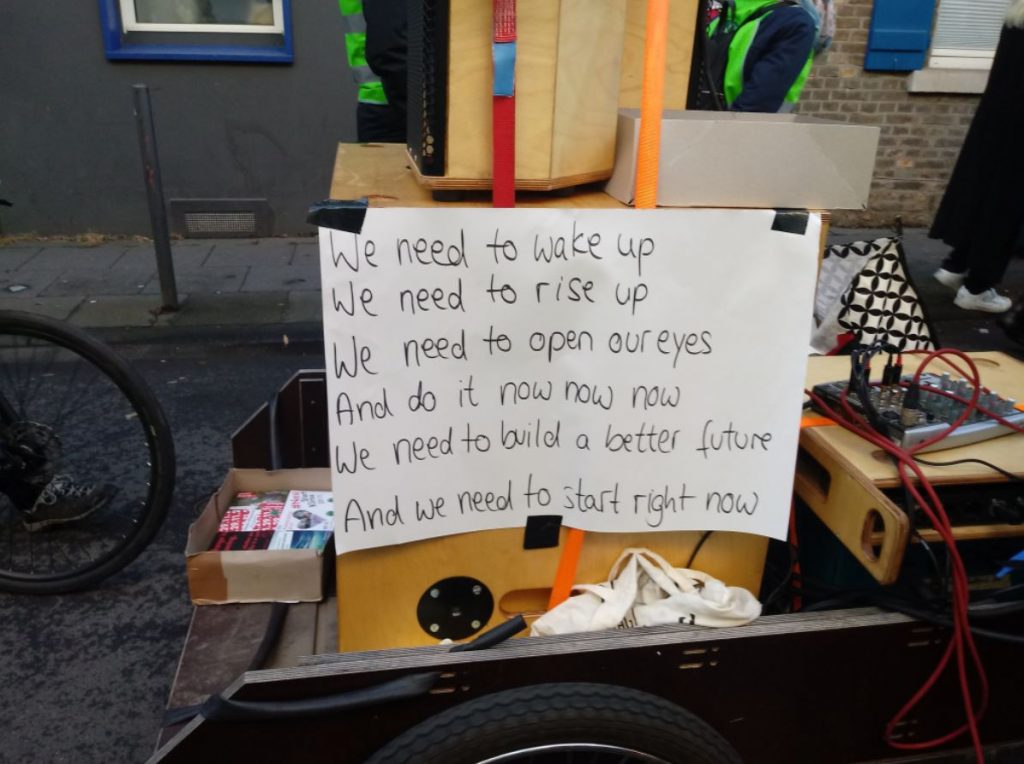

So many things which would once have been relegated to the « eco-weirdo » camp are becoming part of mainstream life, I have the feeling our glass is definitely –at least – half full. Maybe 2021 can be the start of the decade when we turn things around. Maybe the pandemic was the kick that made us feel the dangers of our unsustainable lifestyles and over-exploitation of the limited resources of the planet we live on. At the same time it forced us to shut down and perhaps reconsider. Maybe this was the break ahead of a re-launch. Agreed, time is running short. But we still have a choice. In a piece for DIE ZEIT in December 2020, German journalist Stefan Schmitt commented « There have never been more incentives to think, act and plan in the right direction as there have been this year ». The future, he reminds us, doesn’t just happen. We make it. On that note – bring on 2021!

Related stories around the North:

Canada: 2020 shaping up to be among warmest years on record says WMO, Eye on the Arctic

Greenland: Rise in sea level from ice melt in Greenland and Antarctica match worst-case scenario: study, CBC News

Russia: Northern climate change will cost country €99 billion says Russia’s Minister of the Arctic, Eye on the Arctic

Sweden: Reducing emissions could create up to 3,000 new jobs in Arctic Sweden says mining group, Eye on the Arctic

United States: Indigenous wildfire knowledge to be key part of new Arctic Council project, Eye on the Arctic