Arctic Cold Case: Thousands of mysterious animal deaths finally solved

NASA scientists have finally solved a half-century-old case in the Arctic: the puzzling death of thousands of caribou and reindeer.

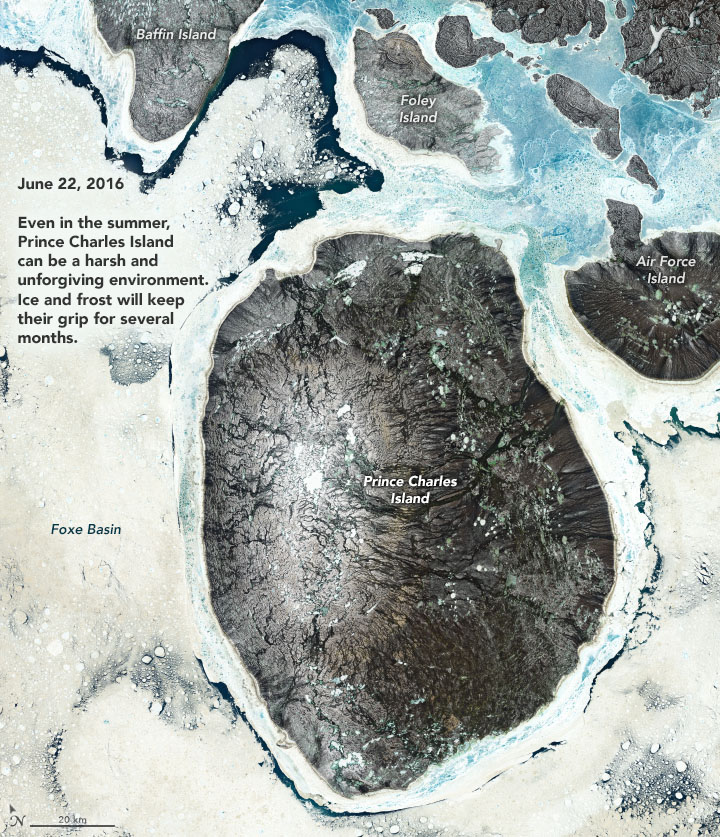

In the summer of 2016, a survey team on a remote island in the Canadian Arctic discovered a grisly sight. Caribou carcasses, by the dozens, littered the tundra of Prince Charles Island, just north of the Arctic Circle in Nunavut.

Death was estimated to have occurred at least several weeks prior to the team’s arrival, perhaps in late winter.

“While some animals died lying down, others appeared to have simply collapsed,” says the report.

This discovery reminded Nasa biologists of a similar scene uncovered half a century earlier and more than 6,800 kilometres to the west.

Forty-two reindeer were found foraging among the skeletal remains of a herd on St. Matthew’s Island, a remote patch of Alaskan land in the Bering Sea. What makes it most puzzling is that only three years earlier, the same herd numbered 6,000 animals.

Same species, different animal

Although caribou and reindeer are the same species, they are not the same animal.

Caribou live in North America, are migratory, and move in large herds between breeding grounds.

Reindeer, on the other hand, are found in Europe and Asia. They have adapted to domestication and can be used to pull sleds and be milked like cows and goats. Various testimonies even state that reindeer milk has a sweet taste and resembles melted ice cream because of its high-fat content (six times that of cow’s milk).

A key attribute that caribou and reindeer share is that they are herbivores that feed on lichens and plants.

“In late fall and early spring, they use their sharp hooves to break through the icy crust on northern lands to reach this food source,” reads the report.

To survive the long Arctic winter, they know how to manage their energy reserves efficiently. But on both Prince Charles Island and St. Matthew Island, the herds ran out of time.

“The data told the tale”

To find out what happened to the two herds, scientists reviewed extensive weather data from both islands.

And there laid the answer.

For the Prince Charles Island caribou herd, major storms occurred in April 2016, a time when the group’s energy reserves are typically at their lowest.

Wind and snow from these storms created an unusually dense snowpack and researchers determined from the data that “the caribou, already weakened at the end of a long winter, starved to death when they were unable to break through the dense snow and ice layer to reach the food they needed”.

Following this discovery, they went back to the 1963-1964 data on St. Matthew Island. They found that it was one of the harshest winters on record in the Bering Sea Islands.

Unable to break through the hard crust, the huge herd of reindeer was unable to access vital nutrients. For the 6,000 reindeer, there simply wasn’t enough food available when they needed it most. By 1966, there were only 42 survivors left.

Thanks to satellite data, NASA was able to close the cold case of the mysterious deaths of caribou in Canada and reindeer in the Bering Sea Islands occurring half a century apart.

“The data told the tale,” concludes the team.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Illegal hunting of caribou herds along Northwest Territories winter roads running rampant, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Climate change worries Finland’s young reindeer herders, Yle News

Russia: In Russian tundra tragedy, up to 80,000 reindeer might have starved to death, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: The Arctic Railway – Building a future or destroying a culture?, Eye on the Arctic

United States: Biden, Trudeau agree to ‘safeguard’ caribou calving grounds in Alaska refuge, CBC News