2021 was 6th warmest year on record, NASA and NOAA find. Canada definitely felt the heat

Temperature across the planet was roughly 0.84 C above the 20th-century average

The numbers are in: Earth is still running a fever.

NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released their annual assessment of global temperatures and found that 2021 was the sixth warmest year on record.

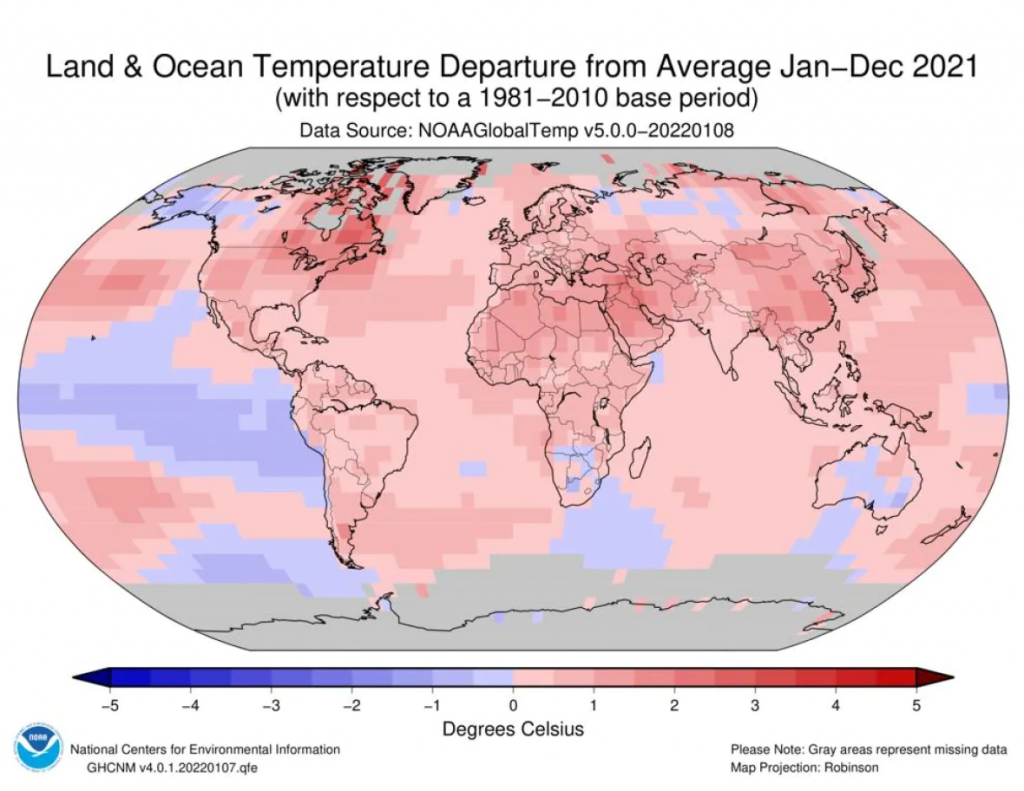

NOAA recorded global land and sea surface temperatures that were 0.84 C above the 20th century average, while NASA recorded 0.85 C.

“It’s certainly warmer now than at any time in at least the past 2,000 years and probably much longer,” said Russell S. Vose, the climate analysis chief of NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), in a teleconference.

While the ranking isn’t the most important gauge of climate change — Vose pointed to others, such as ice-sheet melt, changes in animal behaviour and migration patterns — it’s a good indicator of Earth’s warming trajectory.

“This is just one indicator of a world that’s warming,” said Vose. “The last seven or eight years have been the warmest on record. It’s pretty clear that it’s getting warmer.”

NCEI climatologist Ahira Sanchez-Lugo compared the data to being like a person’s annual checkup.

“We’re constantly taking Earth’s vital signs. And not only do we archive it, but we analyze it to help us understand how healthy the Earth is,” she said.

“When you go to your annual health checkup, the doctor is collecting data from you — they weigh you, they take your blood pressure, they take a blood sample. And not only do they archive that information, but the doctor looks at it year-to-year to see if there are any changes and know how healthy you are.

“So all of [this] is telling us that the Earth’s climate is changing.”

The two U.S. science agencies said that some of the notable climate events of 2021 were: the heat wave that crushed the Pacific Northwest; another heat wave that impacted Europe and the first rainfall on the Greenland ice cap.

While 2021 placed in the Top 10 of hottest on record, the fact that it didn’t rank higher wasn’t a surprise to climatologists. That’s because it was a year with La Niña, a cooling of the Pacific Ocean that has a cooling effect across parts of the planet.

“Once we started with La Niña, we already knew that it wasn’t going to be a record-warm year,” said Sanchez-Lugo. “But we knew that it would be a Top 10 year because of how warm we’ve been so far.”

On Monday, the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) had released its annual findings, placing 2021 as the fifth warmest, at 1.1-1.2 C above 1850-1900 levels. The agency also noted that the past seven years were the planet’s warmest “by a clear margin,” with records dating back to 1850.

There are always slight differences in climate agencies’ findings, due to the various methods used to collect and analyze the data.

“It doesn’t mean that there’s anything wrong with one or the other dataset; it just means that we’re doing things differently,” Sanchez-Lugo said. “But when you look at the entire time series … both datasets are saying the same thing: that the temperatures for each decade continue to increase.”

Looking ahead, Vose said, there’s a 99 per cent chance that 2022 will rank among the Top 10 warmest, a 50/50 chance or less that it will rank in the Top 5, and a 10 per cent chance that it will rank first.

Earth’s warming is being driven by an increase in heat-trapping gases, like CO2, being pumped into the atmosphere, Vose said. Last year set a record for atmospheric CO2, at 419 parts per million, recorded by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in Mauna Loa.

With this upward trend comes serious impacts: increasing droughts; more frequent and more persistent heat waves; flooding; forest fires; and impacts on human health.

“We are going through climate changes here and now,” Sanchez-Lugo said.

Canada’s records

It may not come as much of a surprise that Canada had its own Top 10 record-setting year in 2021.

At the end of June and beginning of July, the eyes of the world were focused on British Columbia as record-setting temperatures were shattered during a deadly heat wave. The town of Lytton — which broke Canada’s hottest temperature record at 49.6 C — was destroyed after wildfires tore through the community, essentially obliterating it.

That heat wave also contributed to 570 deaths in B.C. alone.

But it wasn’t just the West Coast that felt the heat; almost every province experienced a heat wave or higher-than-normal summer temperatures.

“If you stuck a thermometer into Canada this past year, it would be 2.4 degrees warmer than the normal would be,” said David Phillips, senior climatologist at Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). “The only other years that were warmer were 2010 — that was the warmest year in 74 years — and 1998.”

But if you think it was those wicked summer temperatures that drove up our annual temperature, you’d be wrong.

“We often hear globally [that] we’ve warmed up by one degree in the past 200 years,” Phillips said. “Well, in 74 years, [Canada has] warmed up by 1.9 degrees in that period. And the one season that is warmed up the most is winter … by 3.7 degrees, nationally.”

Still, the summer heat waves were startling to Phillips, who has been a climatologist for more than 50 years.

“Even for me, it was a shock to see the impacts, the effects of this extraordinary warming,” he said. “I think what was so interesting was that Canadians were witness to it.… We’d read reports on it and documentaries, but for us, it really hit home. This wasn’t something that occurred in Bangladesh or Botswana. This was occurring in Burnaby and Burlington.”

As for North America as a whole, NOAA said it was the continent’s seventh warmest on record, with a temperature 1.4 C above average. Nine of the continent’s 10 warmest years have all occurred since 2001, with 1998 rounding out the list.

But the climatologists all said the message is clear: Earth’s temperature trend is climbing upward. Globally, the warmest years on record have all occurred between 2013 and 2021.

When asked when we might expect to reach 1.5 C — the global threshold of warming set out by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) — Vose noted the most recent IPCC report suggests there’s a 50/50 chance that will happen in one year of this decade. But the global average “will almost certainly” exceed 1.5 C in the 2030s or 2040s, he said.

“So we’re not there yet, but we’re approaching that point. And that trajectory is unlikely to change as long as we keep emitting greenhouse gases.”

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: 30–50% of critical northern infrastructure could be at high risk by 2050 due to warming, says study, Eye on the Arctic

Greenland: Oldest Arctic sea ice vanishes twice as fast as rest of region, study shows, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Thawing permafrost melts ground under homes and around Global Seed Vault in Svalbard, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: City in Arctic Russia cooling ground to preserve buildings on thawing permafrost, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: Bering Sea ice at lowest extent in at least 5,500 years, study says, Alaska Public Media