Baffinland promotes proposed production increase at Nunavut regulator meeting

Baffinland Iron Mines Corp. says it will stop production at its Mary River iron mine, end shipping and cut jobs to about 80 on site if its request to increase its 2022 production isn’t approved by the Nunavut Impact Review Board.

About 300 Inuit are now employed at the mine, the company said.

“That’s a lot of lives that will be impacted,” said Baffinland’s vice-president Megan Lord-Hoyle Tuesday at the review board’s community roundtable in Pond Inlet.

“We want to protect those jobs.”

Baffinland is preparing for mass layoffs starting at the end of August if its production increase proposal is not approved.

Lord-Hoyle said in September Baffinland would exceed its approved ore production of 4.2 megatonnes and would have to downsize its workforce, remove equipment and shut everything down if it can’t increase production.

Baffinland’s need to boost production — and what it would and wouldn’t do if that doesn’t take place— was never far away during the roundtable.

In 2018, the company was given a temporary approval to up its production from 4.2 million tonnes to six million tonnes, but that approval expired at the end of 2021.

The Nunavut Impact Review Board (NIRB) decided to hold the community roundtable to gather feedback from community members after Northern Affairs Minister Dan Vandal rejected an earlier request from Baffinland for an emergency order to produce more ore until the end of December, suggesting the company go through the NIRB instead.

Lord-Hoyle and others from Baffinland tried to put their best face forward at the round table.

But this effort wasn’t always successful as comments from the affected communities of Pond Inlet, Igloolik, Sanirajak, Arctic Bay, Clyde River, Resolute Bay and Grise Fiord, often honed in on the mine’s negative impacts from shipping and dust.

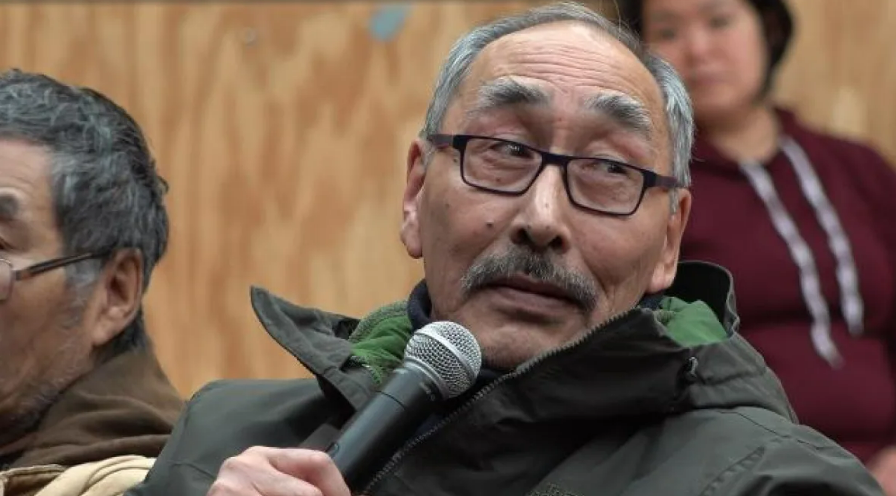

To argue its case, Baffinland brought in its special advisor Paul Quassa of Igloolik, a former Nunavut premier and one of the chief negotiators for the Nunavut land claims.

Quassa, wearing a shirt with a Baffinland logo, touted a “better future” instead of potential job losses due to a possible mine closure, citing the roughly 250-plus Inuit employed at Mary River.

“We have never stopped the Inuit from having employment with Baffinland,” he said, adding that it would not be fair to stop the mine’s production due to a “disagreement.”

That disagreement refers to the criticism from some affected communities and their hunters and trappers associations, who do not support Baffinland’s desire to increase its production.

Quassa said Mary River’s Inuit workers support the production increase. He said they also contribute to the local economy by purchasing hunting equipment.

“This is the benefit we see in the communities and communities are very aware … how employed people are benefiting the community,” he said.

Quassa also promised more Inuit involvement: he said committees associated with the mine’s operations would be “more independent” from Baffinland management, and that Inuit would be more involved in these groups, along with more Inuit traditional knowledge.

Quassa urged Inuit to listen to the elders who helped select resource rich Inuit lands when they negotiated the land claims in the 1990s.

“Nunavut cannot operate on its own,” Quassa said. “We have to make supplemental money outside the territory.”

As for shipping, Quassa said Baffinland monitors shipping “really well.”

But the company plans to reduce the number and frequency of ships it uses to transport ore to limit disturbance on marine mammals.

So this year three or four of the huge ore carriers will go by at the same time “so that the noise may be reduced by doing that.”

Jobs message resonates

Quassa’s pitch for economic benefits from jobs largely resonated. One woman from Sanirajak, who joined the round table remotely, said jobs at Baffinland help employees stay sober due to the mine’s policy of zero tolerance for drugs and alcohol.

But dust from the mine was an irritant that wouldn’t go away.

To that, Baffinland had some responses, including that it would possibly cover ore piles and put up wind fencing around Milne port.

But Lord-Hoyle said dust, from the mine or elsewhere, would be always visible because the earth is naturally red.

The company is waiting for the results of an independent audit of dust and its recommendations, she said — “if we are in the position to implement them.”

Lord-Hoyle said the company would only blame itself if the NIRB doesn’t approve the proposed production increase.

The review board has not yet given a date for their decision; Minister Dan Vandal hopes to hear by Aug. 26.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Nunavut seeking solutions for 90 unfilled teaching positions, CBC News

Russia: New mining project sets sights on Chukotka in Russia’s eastern Arctic, The Independent Barents Observer