Former candidates call to improve elections for Indigenous voters in Quebec

Missing names and missing voter cards, candidates say too many northern voters turned away

Two Indigenous candidates who ran — and lost — in the last provincial election say Quebec is failing Indigenous and northern voters and they worry there is no real desire to fix what’s wrong.

Maïtée Labrecque-Saganash and Tunu Napartuk both ran in the northern Quebec riding of Ungava and came in second and third, respectively. Denis Lamothe, from the ruling Coalition Avenir Québec, was reelected on Oct. 3, for a second term with 36.2 per cent of the votes.

And for the second straight election, voter turnout in Ungava was just above 30 per cent — the lowest in the province by far. The provincial voter turnout was 66.1 per cent.

Both Napartuk and Labrecque-Saganash say that low voter turnout is a direct result of systemic barriers built into the way elections happen in the province, and not voter apathy.

“These [barriers] support a false narrative that we don’t care about politics, but the reality is … a lot of people were turned back at the polls,” said Labrecque-Saganash, who ran for Québec Solidaire (QS) and lives in the Cree community of Waswanipi.

QS had experienced veterans working on Labrecque-Saganash’s campaign and observers in several Cree communities on election night, who said “they’d never seen anything like it,” said Labrecque-Saganash.

In the days after the election, stories emerged from the Cree communities of voters unable to cast their ballot for a variety of reasons, despite having voted successfully in past provincial elections. In Nunavik, there were stories of voter cards arriving late or not at all.

“Quebec was the last province to give voting rights to Indigenous people in 1969. To see that it’s still so hard for us to cast a ballot … to me is very telling,” said Labrecque-Saganash.

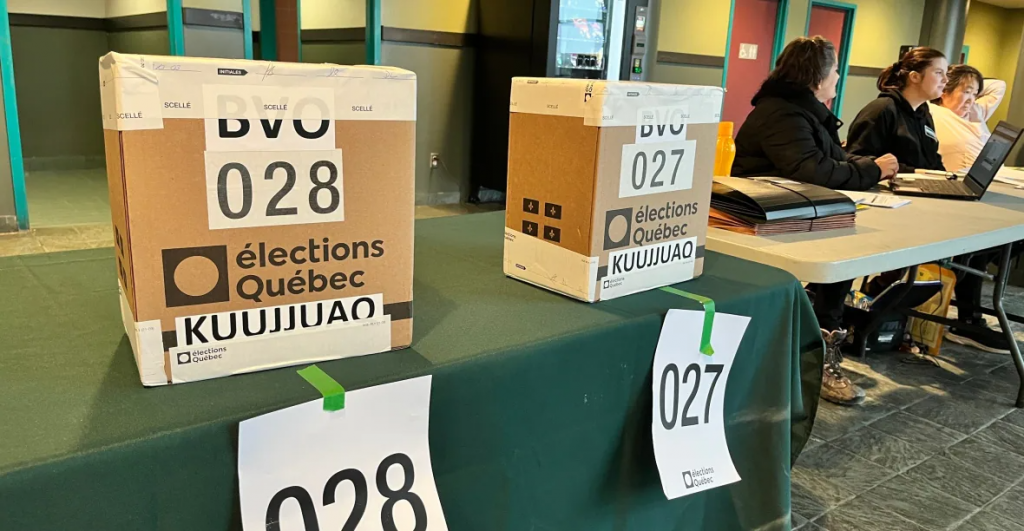

Tunu Napartuk, who ran for the Liberal Party of Quebec, said he is personally aware of at least 50 voters who were turned away in Kuujjuaq alone, with similar stories in all of the Nunavik communities.

“These are people who are permanent residents. They were born, raised and continued to live in their communities. They have always voted,” said Napartuk.

Napartuk said the irregularities and failings of the electoral system in the north are “unfortunate and disheartening,” and he called out Elections Quebec to do better.

Earlier and longer presence

Napartuk said the entity that oversees elections needs to hire local workers who speak Inuktitut and Cree and to set up lines of communication at least a year before an election. He also said teams who work to update the voters list need to be at work in Indigenous communities several months before election day, not the week before as is the case now.

“You’ve got to have a certain personality of openness. [Elections Quebec] cannot expect their staff to be able to make those connections a few days before election day,” said Napartuk.

Some observers suggest Quebec also needs to allow people to be added to the voters list on the day of an election, as is allowed in federal elections by producing two pieces of identification, proof of address and swearing an oath.

Napartuk says that may help some Indigenous voters, but he also warns it won’t solve the problem for everyone, as many Nunavik voters don’t have pictures on their medicare cards, because it’s hard to get an eligible photo.

“So having the proper IDs to be able to prove who they are … that in itself is a huge challenge,” said Napartuk. He suggests Elections Quebec should instead consider appointing officials from each community, who can be allowed to officially vouch for people.

Napartuk also says the Cree and Inuit communities of northern Quebec should have their own riding. Ungava is the largest riding in Quebec, covering 855,000 sq. km.

Elections Quebec response

Elections Quebec turned down a request by CBC News for an interview with the province’s chief electoral officer, Pierre Reid.

Spokesperson Julie St. Arnaud-Drolet said they have set up a working committee made up of large electoral divisions, including Ungava to “examine, among other things, the obstacles to voting in Indigenous communities.”

“We are still taking stock of the October 3rd election. Over the next few years, we will be clarifying the new procedures that will be put in place for the 2026 general election,” said St-Arnaud Drolet, adding that Elections Quebec cannot initiate electoral reform, but can respond to a request from the provincial government.

Requests for comment from Quebec’s Indigenous Affairs Minister, Ian Lafrenière, about whether the government was open to reform were not answered.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Online security experts warn against online voting in territorial elections in Northern Canada, CBC News