Urgent need for better monitoring of sinking ground across the Arctic says study

Warming temperatures are causing the ground to sink across parts of the Arctic, and a new study is urging better monitoring to track these dramatic changes.

“Our findings suggest that permafrost landscapes are undergoing geomorphic change that is impacting hydrology, ecosystems, and human infrastructure,” the paper, published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, said.

“The development of a systematic [thaw subsidence] monitoring is urgently needed to deliver consistent and continuous exchange of data across different permafrost regions.”

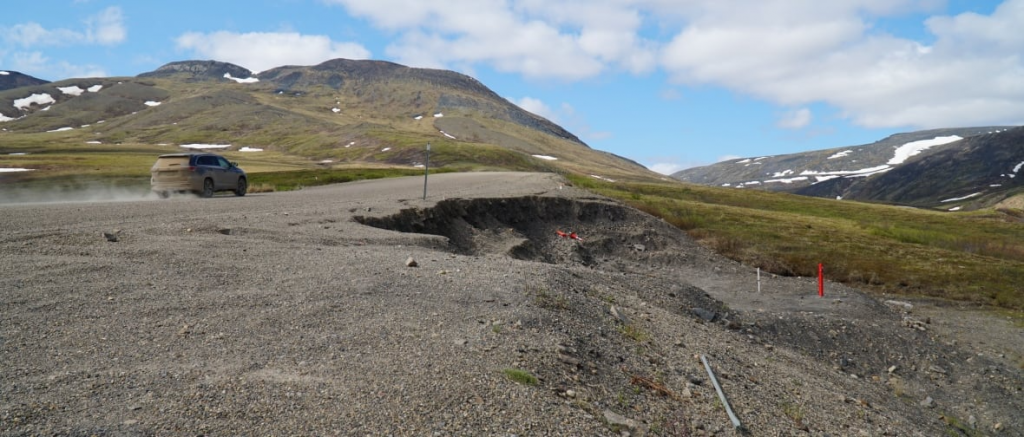

Climate change is causing the permanently frozen soil, known as permafrost, that underpins much of the Arctic to thaw, which leads to destabilizing the ground layers above.

The process is called thaw subsidence and causes the ground at the top to sink and crack.

“Thaw subsidence is a common process in permafrost environments,” the paper said.

“However, outside of obvious engineering applications focused on monitoring built and linear infrastructure, such as roads, railroads and pipelines, monitoring of Thaw subsidence remains limited. Numerous studies, from North American and Eurasian permafrost regions summarized in this review confirmed widespread thaw subsidence.”

Adding in human activity and wildfires is further exacerbating the problem, the paper said.

Not only does this affect the infrastructure and communities and the ecosystem on top, but it also releases carbon monoxide and methane previously trapped in the frozen ground, amplifying global warming.

Strong monitoring in Canada’s N.W.T., Alaska, but data lacking elsewhere

To conduct the study, researchers at George Washington University in the United States examined data from permafrost regions across the globe, including North America, Europe, Asia, and the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau.

They analyzed monitoring efforts, the technologies used to track ground subsidence, and reviewed existing academic literature on the topic.

The study found that areas of Canada and the U.S. had some of the most robust monitoring systems, while data from other regions was inconsistent.

“North American permafrost regions, particularly Alaska and North Western Territories have more developed measurement both in duration and coverage, while Arctic regions of the Northern Eurasia and [the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau] have limited data available for review,” the paper said.

“This does not suggest that the data on thaw subsidence are not being collected in these regions. Language, geopolitical and other barriers may limit availability and accessibility of these data to the public domain.”

The researchers established the gap was largely due to challenges like lack of funding, political hurdles, and differences in how monitoring is carried out.

Better technologies could help fill information gaps

The paper’s authors say that emerging technologies could play an important role in closing these gaps, with satellites, drones, and LiDAR systems, lasers that measure distances, already making it easier to map ground changes across large, remote areas.

Artificial intelligence and cloud computing, which allow massive datasets to be processed quickly and accurately, will also have an important role to play, they said.

On the ground, tools like thaw tubes, which measure how deep the soil thaws, and GPS surveys, are just some examples of cost-effective ways to track changes, they said.

Combining ground based tools with data from satellites could go a long way towards creating a much clearer picture of permafrost thaw worldwide, the paper said.

“Permafrost [thaw subsidence] will play an increasingly important role under warming climatic conditions,” the researchers said.

“Therefore, improving [thaw subsidence] estimates by field studies, remote sensing measurements, and improved modeling is critically needed to provide better understanding of permafrost degradation and its consequences.”

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Québec funds research to adapt Nunavik public housing to thawing permafrost, CBC News

Norway: Thawing permafrost melts ground under homes and around Global Seed Vault in Svalbard, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Melting permafrost may release industrial pollutants at Arctic sites: study, Eye on the Arctic

United States: 30–50% of critical northern infrastructure could be at high risk by 2050 due to warming, says study, Eye on the Arctic