As COP30 nears, new report warns of ‘irreversible’ polar ice loss

As world leaders prepare to meet in Belém, Brazil, for the COP30 environmental conference on Monday, a new report warns of the rapid decline of the planet’s ice, with the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets now moving towards irreversible loss.

The “State of the Cryosphere 2025” is put together by dozens of researchers who study the world’s frozen regions and coordinated by the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative (ICCI).

While the report examines the full cryosphere — from sea ice and glaciers to permafrost and the polar oceans — it gives particular attention to the world’s ice sheets, pointing to places like the Arctic which are losing ice four times faster than they were in the 1990s.

“Current policies risk triggering long-term sea-level rise and loss of coastlines on a massive global scale,” the report says.

“The decisions made by policymakers today on emissions of greenhouse gases will determine how much and how fast seas will rise, as well as wider impacts to the global climate system.”

Greenland melt accelerating

The ICCI was founded after the 2009 COP15 conference as a way to spotlight the global impacts of melting ice.

Their 2025 report gathers what scientists have learned from new studies and describes them for policymakers ahead of COP30.

One of the more troubling trends is that the Greenland ice sheet may be melting faster than scientists thought. The report outlines how new satellite data corrected a bias in older climate models used in northwestern Greenland. The new readings suggest the ice sheet could add 8 to 17 per cent more to sea levels by 2100 than earlier estimates calculated.

In addition, studies are noting the widening of crevasses on the ice sheet as well as rising rainfall, both phenomena that speed up melting and carry water inside the ice, weakening the structure.

And as the surface of Greenland’s ice sheet sinks lower, it’s exposed to more warmer air — a feedback loop that speeds up melting. The report warns that without deep cuts to emissions, the process could eventually cause the loss of most of the ice.

Antarctica close to tipping point

New modelling shows that ice sheets in West Antarctica could start to collapse with less than 0.25 C of additional ocean warming. Once that begins, the loss cannot be reversed on human timescales.

“Substantial irreversible ice loss over the coming centuries, especially from West Antarctica, is therefore likely to be triggered with little or no further climate warming,” the report says.

“Once ice sheet melt accelerates due to higher temperatures, it cannot be stopped or reversed for many thousands of years, even if temperatures later stabilize.”

New mapping of the seafloor around Antarctica has also shown deep troughs that direct warm ocean water below the continent’s glaciers and ice shelves, making them more prone to melt than previously thought.

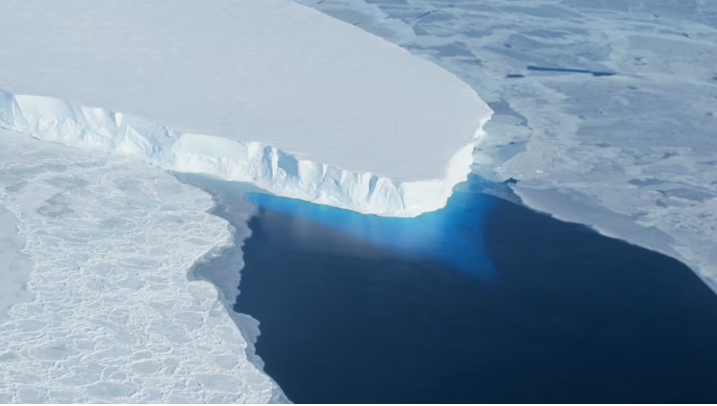

“The two largest glaciers in this region, Thwaites Glacier and Pine Island Glacier, collapse in every model scenario,” the report said.

More water, faster seas

Increasing freshwater is also a concern at the South Pole, the report warned.

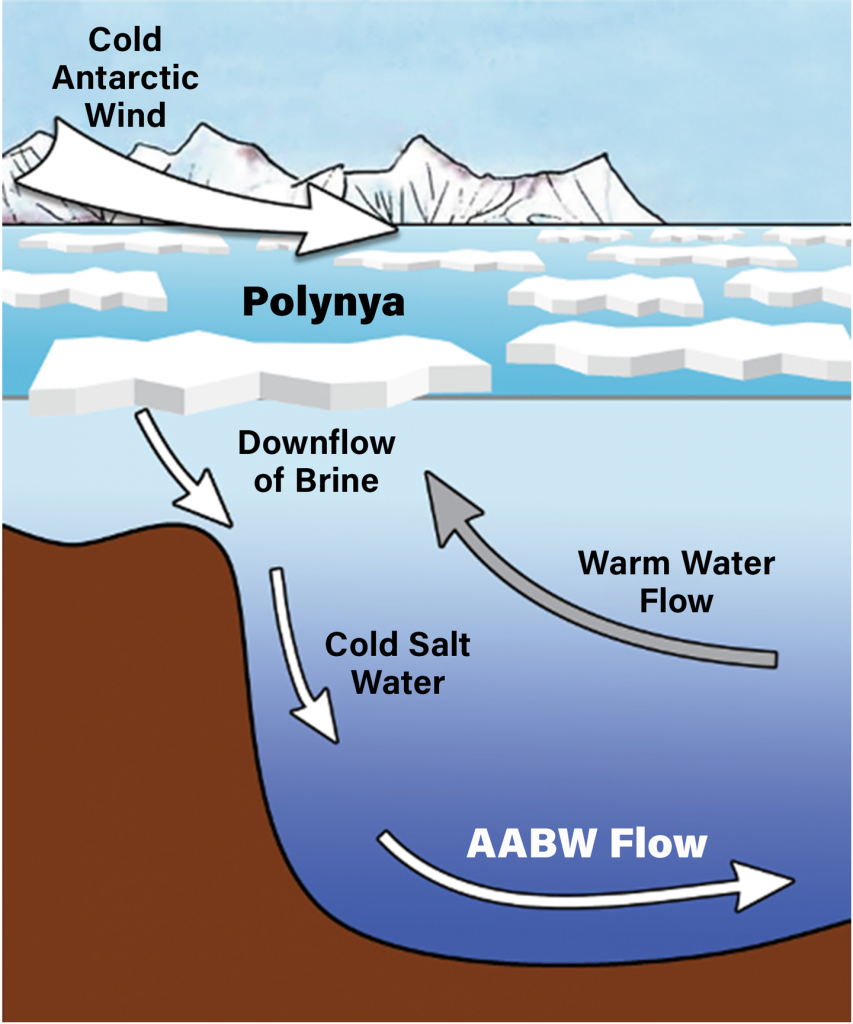

High emissions could double the amount of freshwater coming into the ocean from Antarctica by 2100, and quadruple the amount by 2300, something the report said “risks triggering severe negative global feedbacks, including on ocean currents.”

But lower emissions could still slow the process, the report said.

“If global emissions can be dramatically lowered, the amount of freshwater discharged from Antarctica can be greatly limited in the coming centuries,” the authors said.

A 1 C warning

The report authors also challenge the current international climate policy goal of keeping warming below 1.5 C from pre-industrial levels, saying this measure would not be enough to protect the ice sheets and stop the resulting sea-level rise.

“A temperature target of 1.5°C is too high to prevent widespread global damage from ice loss,” the report says. “Avoiding these impacts would require a global mean temperature that is cooler than present, likely closer to 1 C above pre-industrial levels, or even lower.”

No quick recovery

Once large-scale melting begins and sea-levels rise, the process cannot be reversed within our lifetimes, the authors say.

“Sea-level lowering will not occur until temperatures go well below pre-industrial levels,” the report says, with ice regrowth taking thousands of years.

The report warns that as sea levels rise faster, coastal communities will find it harder to keep up — one reason it calls for halving global CO₂ emissions by 2030 to slow the planet’s accelerating ice loss.

“Otherwise, world leaders are de facto committing to erase many coastlines and displace hundreds of millions of people – perhaps much sooner than we think.”

Comments, tips or story ideas? Contact Eilís at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Wildfire seasons in the N.W.T. unlikely to ease off by next century, study finds, CBC News

Finland: Flooding in Finland is getting worse, new climate report says, Yle News

Greenland: Ocean currents may be driving mercury pollution in Arctic, says study, Eye on the Arctic

Iceland: Resilience, recovery prioritized in Iceland report on Grindavik evacuation, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Weather above normal for 18 consecutive months, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: New NOAA report finds vast Siberian wildfires linked to Arctic warming, The Associated Press

Sweden: Proposal—Sweden’s 2030 climate targets to remain unchanged, Radio Sweden

United States: How the Arctic has been ‘pushed & triggered’ into climate extremes: paper, Eye on the Arctic