How sub-Arctic seas are influencing the Arctic Ocean and what it’s telling us about climate change

The Pacific and Atlantic Oceans are driving changes in Arctic waters in more complex ways than previously recorded and are leading to dramatic changes in the region, says a recent paper.

“We are used to seeing the Arctic Ocean as its own system,” said Kristina Brown, an NSERC Visiting Fellow with Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Sidney, British Columbia (B.C.) and one of the paper’s authors. “What’s so interesting is to see how sub-Arctic oceans are affecting it differently across the pan-Arctic.

“This paper looks closely at the importance of Atlantic and Pacific Ocean waters in the Arctic, and the increasing influence of these sub-polar waters in painting the physical, geochemical, and biological canvas of the Arctic Ocean,” she said in a phone interview from B.C.

The paper, “Borealization of the Arctic Ocean in Response to Anomalous Advection From Sub-Arctic Seas“, was published this month in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

International effort

Researchers in six different countries, including Canada, were involved in the project, headed by the University of Alaska Fairbanks and Finnish Meteorological Institute.

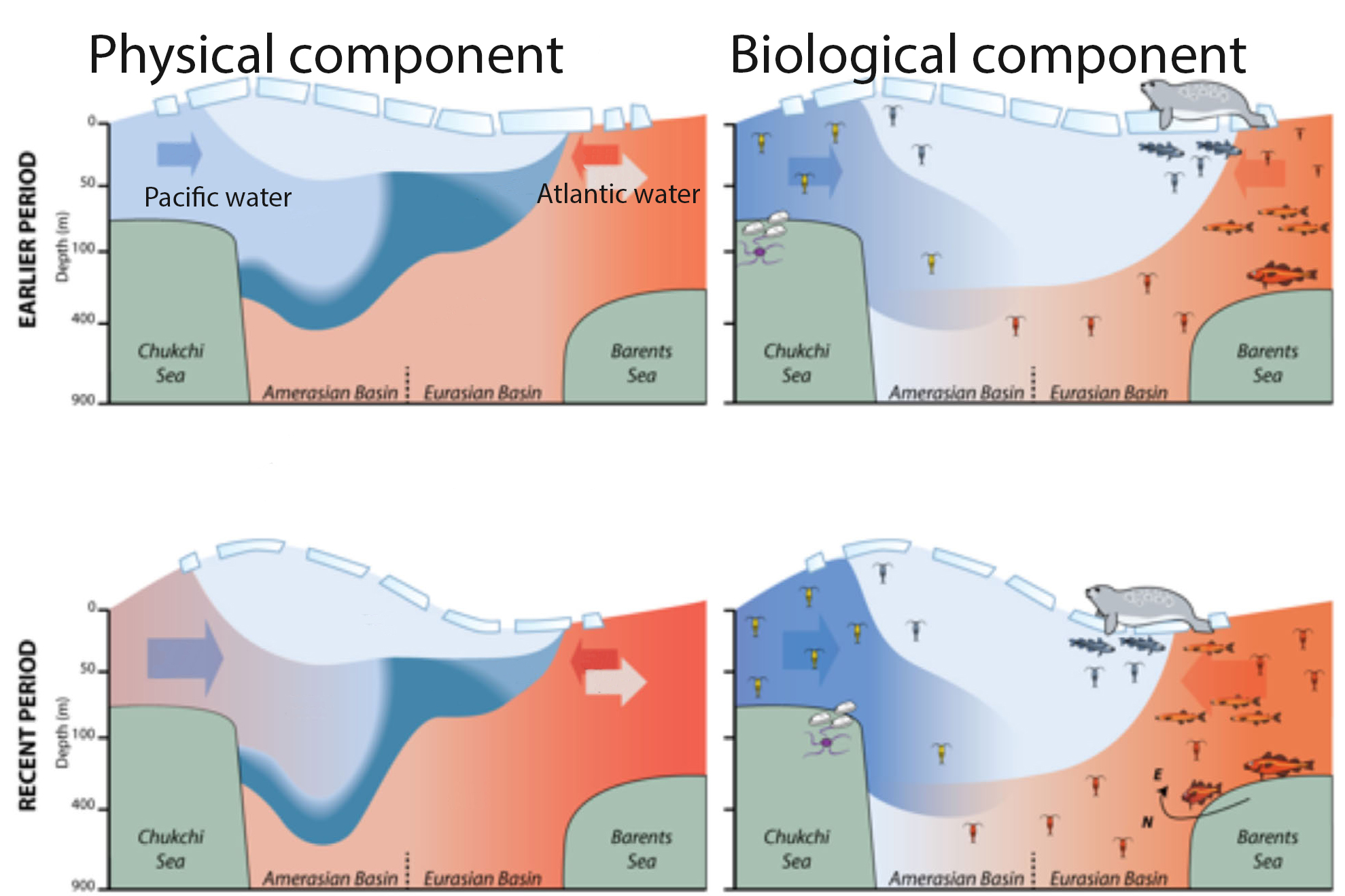

Data was mostly collected from records dating from 1981 to 2017. What researchers found was that the Arctic Ocean’s responses to climate change varied depending on whether the ocean’s Amerasian Basin, influenced by Pacific waters, was being looked at; or wither its Eurasian Basin, influenced by Atlantic waters, was being looked at.

In the Arctic Ocean, fresh water, which is lighter than salty water, rises to the top and acts as a buffer between sea ice at the surface and the warmth of deeper water that could melt the sea ice.

But climate change is altering this delicate balance in pronounced, but different ways, depending on which side of the ocean is being looked at.

Ocean layers and sea ice

On the Pacific side, in the Amerasian basin, the separation of surface and deep ocean layers is more pronounced due to sea ice melt, river water accumulation and the relatively fresh water from the Pacific Ocean. But the increasing fresh water may contribute to a less biologically productive region, because it limits the mixing that brings nutrients to the surface.

But on the Atlantic side, in the Eurasian basin, the researchers found that influxes of warm, salty Atlantic waters are destabilizing the upper layer, making the sea ice in that region of the Arctic Ocean more susceptible to warmth from the deep. This process is making sea ice erosion accelerate, as well as making the water more biologically productive as nutrient-dense water rises to the top.

“For me, what was so fascinating was how different things were in the different regions and how they’ve been moving in opposition,” Brown said.

Regional and community change

Igor Polyakov, a professor at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks and the paper’s lead author, said the changes they’ve noted are just the beginning of the transformation of the Arctic Ocean by climate change.

“It’s even changing the physics of the water,” he said in phone interview from Alaska. “Before it was slow, very slow, but now it is more a turbulent mixing process. It has speeded up.

“But in another 15 years it will be completely different again, because the sub-Arctic waters are changing too.”

Polyakov says the changing oceans will have important implications in coming years for everything from predicting water currents, sea ice loss and weather, to the increasing number of species moving north.

“There’s now salmon and pacific crabs being caught by communities off the Chuckchi Sea,” he said.

“Thirty years ago, when we used Russian heavy icebreakers to get where we needed to go in the Arctic, they had a real problem doing it. Now, we got to those same places and they are completely ice free is summer.

“The changes are so huge and fast, in many ways, the Arctic Ocean now looks like a new ocean.”

Write to Eilís Quinn at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Antarctica: South Pole warmed 3 times the global rate over the past 30 years, new study suggests, Thomson Reuters

Finland: Finland behind on sustainable development goals, Yle News

Greenland: COVID-19 delay, early ice melt challenge international Arctic science mission, The Associated Press

Iceland: Ice-free Arctic summers likely by 2050, even with climate action: study, Radio Canada International

Norway: Norway to expand network of electric car chargers across Arctic, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Record 38C temperature recorded in Arctic Siberia, Eye on the Arctic

Sweden: January temperatures about 10°C above normal in parts of northern Sweden, says weather service, Radio Sweden

United States: Temperatures nearing all-time records in Southcentral Alaska, Alaska Public Media