Harper: #1 Priority in Northern Sovereignty is Protection of Sovereignty in our North

Drum roll, please: Canada announces another Arctic foreign policy statement – without actually announcing much in the way of new policy. Stephen Harper used his best doublespeak when commenting on the new Statement on Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy to reporters last Friday:

Drum roll, please: Canada announces another Arctic foreign policy statement – without actually announcing much in the way of new policy. Stephen Harper used his best doublespeak when commenting on the new Statement on Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy to reporters last Friday:

“[O]ur No. 1 and, quite frankly, non-negotiable priority in northern sovereignty… is the protection and the promotion of Canada’s sovereignty over what is our North.”

I guess in the absence of really convincing reasons to focus so much attention on Arctic sovereignty, Arctic sovereignty becomes its own raison d’etre.

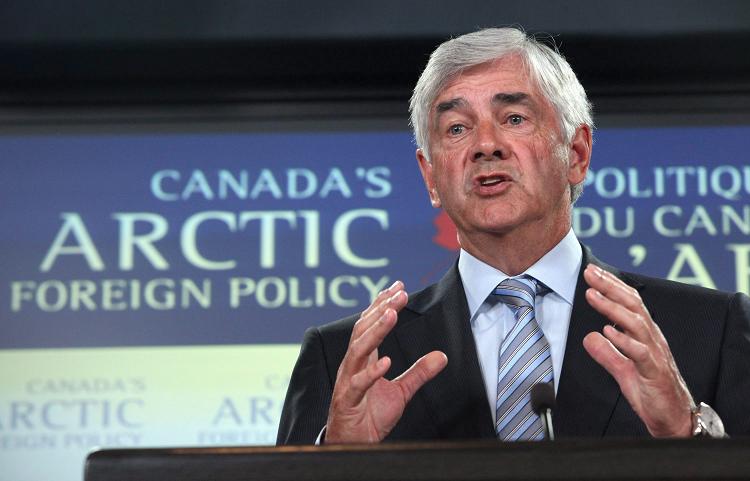

The Statement issued by Foreign Minister Lawrence Cannon on August 20th has few surprises, sticking closely to the script outlined in the 2009 Northern Strategy and its four pillars of sovereignty, environment, development and governance. A handful of things distinguish it from its predecessors:

· Stephen Harper typically goes full-bore on Arctic sovereignty in his speeches about the North, but the policy statements are generally a bit more muted. This one, on the other hand, makes no bones about the fact that in Canada’s “Arctic foreign policy, the first and most important pillar [emphasis added] towards recognizing the potential of Canada’s Arctic is the exercise of our sovereignty over the Far North.”

Readers of my previous blogs will know that I have developed sovereignty fatigue, and this is a perfect example of why. Mired in the Westphalian era preoccupation with territory and borders, the Harper government is treating sovereignty as an end in itself, when it should be viewed as a means; a means to achieve sustainable development, promote good governance and protect indigenous values and the environment. The Statement itself makes clear that the few “discrete boundary issues” we have in the Arctic are well-managed and unlikely to lead to conflict.

So while we all agree there is no sovereignty crisis, protecting some lines on a map is perpetually prioritized over the health and well-being of the North and its inhabitants, in both attention and funding. The Master serves the servant.

· The Statement alludes to the negotiations, and hopefully eventual resolution, of our boundary disputes with the United States over a wedge of territory in the Beaufort Sea between Yukon and Alaska, and with Denmark over tiny, uninhabited and resource-poor Hans Island. There are many fair and equitable possible solutions to these problems, and their resolution would prove a welcome removal of unnecessary irritants in relations with our closest neighbours. If and when they are resolved, I hope the media and Opposition (whoever that may be at the time) applaud the accomplishment, rather than opportunistically decry the loss or forfeit of Canadian territory.

· The Statement confirms that Canada and the United States are in negotiations, however early, to submit a joint agenda for their upcoming Arctic Council chairmanships. (Canada holds the chair from 2013-2015, the USA from 2015-2017). This is encouraging. One of the main institutional challenges faced by the Arctic Council is that its lack of a permanent secretariat (it has rotating two-year chairmanships instead) leads to disjointed and inchoate agendas. Norway, Denmark and Sweden have tried to resolve this dilemma by pursuing a joint agenda and establishing a semi-permanent secretariat during their successive chairmanships from 2006-2013. It is wise for Canada to try to do the same, as any chance for real reform and progress in Arctic governance depends on buy-in from the United States. It will be interesting to see what goals they decide to jointly pursue.

· The mark of a bona fide region in international relations is when a group of states starts to develop and act towards common interests, to the exclusion of third parties. This has been a sluggish process in the Arctic. Circumpolar relations begin in earnest at the end of the Cold War, but it has been slow to shed its East vs West (or Russia vs the Rest Of Us) mentality. But for all the chest thumping over the 2007 Russian flag planting and potential disputes over the Lomonosov Ridge, the process of claiming the northern continental shelf seems to have brought the Arctic coastal states together. Because the alternatives here seem to be: 1) each of the five Arctic coastal states annex huge swathes of Arctic seabed, presumably loaded with oil and gas; or 2) all concerned parties from around the world get together to form a treaty and make the Arctic Ocean and its continental shelf the common heritage of all mankind. No gold stars for guessing what the preference of the Arctic 5 is. Indeed, that’s why we now have an ‘Arctic 5’ instead of just an Arctic Council. And that’s why the European Union’s application to join the Arctic Council was rejected by Canada.

This is what the Statement has to say about outsiders:

“Increasingly, the world is turning its attention northward, with many players far removed from the region itself seeking a role and in some cases calling into question the governance of the Arctic. While many of these players could have a contribution to make in the development of the North, Canada does not accept the premise that the Arctic requires a fundamentally new governance structure or legal framework. Nor does Canada accept that the Arctic nation states are unable to appropriately manage the North as it undergoes fundamental change.”

Other than its prioritizing of sovereignty, the new Statement is a good, solid document that at the very least clarifies Canada’s intentions for those who don’t want to read through endless PMO and DFAIT press releases and speeches. But it fails on one further account – an almost complete lack of creativity and innovation. Perhaps in its joint Arctic Council agenda with the United States, Canada can develop some northern governance arrangements that are as forward thinking at an international level as they have been on the domestic side.