Language rights under scrutiny in Finland

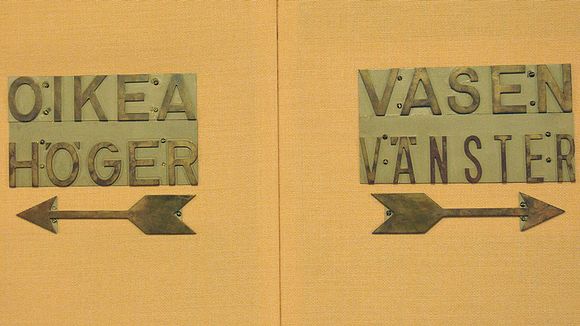

A new cabinet report filed with Parliament notes that the rights enjoyed by different language groups in Finland are far from being on an equal footing.

There is lots of room to improve services in Swedish – to say nothing of services for Russian or Sámi speakers.

There have been, and continue to be problems securing services in both official languages, Finnish and Swedish, especially in social and health care, according to the report on how legislation on language policy works in practice. The report also highlights some of the negative attitudes that have been directed against different language groups in Finland.

The national language strategy seeks to boost the viability of both national languages, and the opportunities to learn both languages. Authorities should also be better able to inform members of all minority language groups about ways to meet and maintain their mother tongues, it says.

At present, there are 148 different languages spoken as mother tongues by residents of the country. The development of services for speakers of minority languages has received some international attention of late, as well. The Council of Europe recently recommended that Finland should give more support particularly to the use of the Russian language.

However, deficiencies in the availability of language services do not concern only immigrant communities. Justice Minister Anna-Maja Henriksson, herself a member of the Swedish-speaking minority, noted to Yle that the Helsinki region is home to 35,000 Swedish speakers and more needs to be done to ensure services for them as well.

Sámi vulnerable

The cabinet’s report also states that the position of the language of the indigenous Sámi people is fragile, and that their linguistic rights are only randomly observed. It is especially difficult to get public services in spoken Sámi. A major problem is that many Sámi children live outside traditional Sámi areas and so do not get instruction in their native language at school.

As for the sign language rights, there has been some progress. Still, there are concerns about the future of children who use sign as their first language and how well their right to their own language and culture can be ensured. The Finnish-Swedish form of sign language is at even greater risk of completely disappearing.

Growing diversity

The number of Russian speakers and Estonian speakers especially has grown, while their need to be informed in their own language has grown apace.

Of Finland’s population, 4.5% speaks a language other than Finnish or Swedish as a mother tongue. Some of these such as Sámi, Romani, Tatar and Karelian have been spoken in Finland for hundreds of years, or in the case of Sámi for millennia.

The largest linguistic minority in Finland is the Swedish-speaking population, followed by Russian, Estonian, Somali, English and Arabic speakers.