No salvage plans for buildings after mine cleanup in Canada’s Northwest Territories

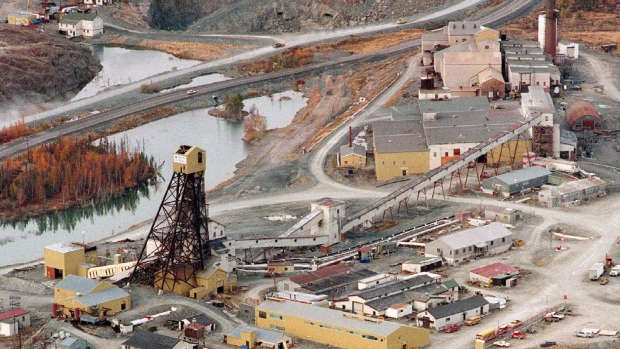

The federal team tasked with cleaning up the old Giant Mine site on the outskirts of the city of Yellowknife says there’s no plans to salvage any of the buildings, but they’re open to suggestions from the public on the issue.

The mine, located in Canada’s Northwest Territories (N.W.T.) produced more than 200,000 kilograms of gold during its more than 50 years in operation. But it’s sat idle since 2004 after the old owners left, and now it’s up to the federal government-funded team to clean up the mess.

Over the next few years, crews will dismantle the familiar silhouette of the mine’s wooden “C” headframe. That needs to go so they can seal off the mine shaft below. The plan to remove all the buildings, many of them are laden with asbestos and other contaminated materials.

Once that happens, there won’t be much evidence that anything was ever there.

Remediation plan

“It won’t be so obvious to them. In 20, 30 years, it’ll just be a cleaned up site,” N.W.T. Mining Heritage Society president Walt Humphries says. “They won’t have much to remember.”

For some, Giant Mine’s place in the city may already be fading into the past.

“I got a son working in the mines up north… but I didn’t have no connection to this mine,” says resident Pearl Slade.

Others would like to see parts of the old structures preserved.

– Walt Humphries

“The headframe at Giant is not quite as visible from a lot of locations,” she says. “Really, the one that’s at Con is kind of been a visible landmark for everybody for years.”

The city’s been trying to decide what to do with the Robertson headframe at nearby Con Mine for almost as long, as there seems to be just as little progress on that issue.

Once road work along Highway 3 is completed, Yellowknifers won’t even have occasion to drive past the old site very much. The Mining Heritage Society hopes to have a museum and hiking trails on the site. They also hope to be able to save Giant’s smaller “A” headframe.

“It is a symbol of mining in this area and there aren’t many of these old wooden headframes left,” Humphries says. “If we can preserve it it’d be wonderful, if we can’t it might build a replica or something.”

Giant Mine also has a darker history than Con Mine. Nine men were murdered during a 1992 labour dispute, one of the bloodiest in Canadian history. Now one of the most contaminated sites in the country with 237,000 tones of arsenic trioxide in underground chambers. The clean up bill is expected to cost at least $1 billion.

Humphries says that legacy needs to be remembered.

“History is history. You record it all and then future generations can make up their own mind. As a historical group, we’re not pro- or anti-, we just try to record the history and present it to people. The good the bad.. the ugly and the beautiful.”