Franklin search: Relatives hope for answers in Arctic mystery

Simon Ekins was a young British lad of about eight when his father told him they had a famous explorer in the family.

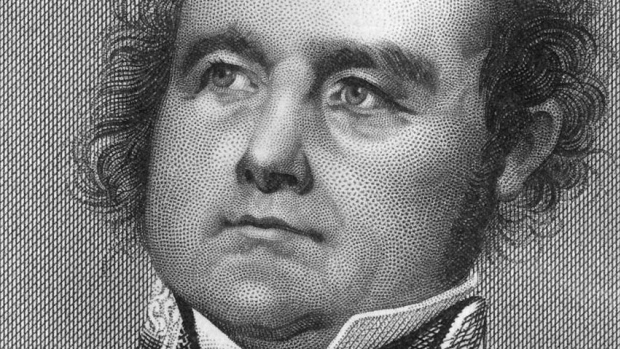

Now, nearly six decades after his imagination was first fired up by thoughts of his great great uncle Sir John Franklin, Ekins relishes the idea that Parks Canada is trying to unravel the mystery still hanging over the naval officer’s doomed 19th-century Arctic mission.

“It is important that both the British and Canadian people are kept aware of the story of the expedition,” Ekins said in an email from his home in Horncastle, a small market town near Franklin’s birthplace in eastern England.

“It is part of our heritage of both our nations and the courage shown by these explorers is a fine example to our current generation. We should be proud of their achievements and [see them] as a lesson in the resilience of

human endeavour.”

That resilience was tested by Franklin and the 128 men he led after HMS Erebus and HMS Terror left England in 1845 in an attempt to find the Northwest Passage.

But the expedition was ultimately doomed, the ships beset by ice, abandoned and ultimately lost somewhere in the frigid waters off the territory that is now Nunavut.

Ekins, along with other relatives of expedition sailors and those who tried later in the mid-19th century to find them, welcomes the efforts Parks Canada has made to try to track the fate of Erebus and Terror. This year’s instalment of the search ended recently with no sign of the ships, but artifacts and bones were gathered from sites on King William Island.

For Ekins, any discovery of the ships could help shed light on the many unanswered questions that remain in what is considered the greatest disaster in British polar exploration.

“If the ships are found either intact or indeed in some pieces, it is possible that the icy conditions prevailing at the time and since will have preserved much of the archeology surrounding the site and can only add vital information and evidence as to the reasons why the crew had to ultimately leave the ships.”

But the first story Ekins heard about Sir John Franklin did not revolve around his final, fateful 1845 mission to the frigid waters of what is now Nunavut. Instead, Ekins heard about Franklin’s early life in the Royal Navy and his time at the Battle of Trafalgar four decades earlier.

“This led me to follow his career, firstly in his overland expeditions in Canada, following the Coppermine and Mackenzie rivers, mapping much of the Arctic coastline of northern Canada and finally to read all I could about the last expedition and the fascination surrounding the story.”

Ekins, who lives near Franklin’s birthplace in eastern England, says his great great uncle was a kindly, modest and unassuming man who was a “fine leader.”

Martin Crozier, a cousin of Francis Crozier, the second-in-command on the Franklin expedition and captain of the Terror, also welcomes the Parks Canada initiative.

“It’s very interesting what they’ve been doing over the years,” he said in an interview from central Europe.

Crozier, however, sees more than an interest in history at play in the current search.

“Really and truly, it wouldn’t be being done if Canada didn’t want to prove that the North actually does belong to Canada, because by finding the route of those ships or finding the ships, it proves beyond any doubt that that land belongs to Canada,” Crozier said.

Crozier also sees an opportunity to shed more light on questions that remain about the expedition.

“It was a mystery as to where the men disappeared to,” he said.

“Everybody is depending on folklore. There is nothing definitive. Both ships were equipped with steam engines inside. They were used as locomotives beforehand so they’re pretty big objects and they are likely to be sitting on the seabed somewhere still in existence because they’re big hunks of metal.

‘Beyond everybody’s wildest dreams’

“One day, these objects will be found and then it will give us more information as to what actually happened.”

Or maybe steel tubes from the ships that could have been repositories for papers written by sailors will eventually turn up.

“It could yet be the treasure trove of information of data beyond everybody’s wildest dreams. It’s all possible,” said Crozier

Answers, suggests Crozier, could also bring relief to families who have no definitive idea of what happened to their relatives on the Franklin expedition.

“It’s rather like when a plane blows up and everybody gets smashed to smithereens. Those families never have a sense of closure.”

For the relatives of those who sailed on the Franklin expedition, or sailed off later trying to find it, the current search is also a chance to remind others that there are lessons history can teach – if they are remembered.

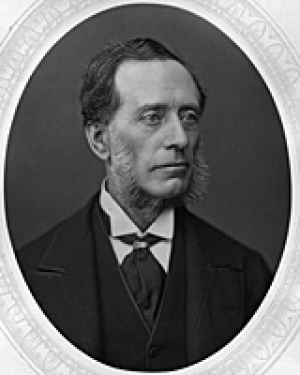

“There’s no harm in looking back in history,” said Paddy McClintock, whose great great uncle Sir Leopold McClintock led the 1850s mission that found the most significant document discovered from the Franklin expedition: a sheet of paper that confirmed the ships had been abandoned and Franklin was dead.

“If you look at what’s happening in the world today….we’re just shrugging off history,” McClintock said in an interview from his home in southern England.

“I almost think of history as unfashionable. Maybe it should be made fashionable so we can learn from it because God knows we should be learning from history.”

McClintock sees the opportunity to discover more about the Franklin expedition as a chance to learn lessons around everything from the importance of strong leadership to the significance of dedicating one’s life to service, something he says his great great uncle did with considerable devotion as he led the mission commissioned by Franklin’s widow, Lady Jane Franklin.

“Service is a worthy thing. It should be translated into a modern context.”

“When he joined his ship, he was weighed against the ship’s dog and the ship’s dog was heavier than he was,” his great-grandaughter Sylvia McClintock says.

McClintock, who went on to a storied naval career, was the “type of man who inspiried tremendous loyalty in his sailors,” she says.

McClintock is well known for his adoption of sledging in Arctic missions.

“Until then, the British Navy have been very prissy about the Inuit and saying, Oh … they don`t know anything.’ And McClintock was saying, ‘Actually, they survived here for thousands of years. They must know something. They must be doing something that we’re not doing.’”

Sylvia McClintock, a great grandchild of Leopold McClintock, also sees modern lessons in the story of the Franklin expedition and the subsequent searchs.

It is, she suggests, important now to have an awareness or understanding of what happened on those missions “to highlight just how incredibly brave, possibly stupid, these men were.”

“They knew what the risks were and then prepared to do it,” she said in an interview from her home west of London.

She looks at the way the sailors would have had to get on with one another as the expedition dragged on, and sees a modern-day lesson in the need to always have a “a spirit of compromise.”

Now, she says, the Franklin expedition story matters “because it’s a tale of terrible tragedy and also because they managed to survive for so long.

“They probably managed to survive probably three or four years, which is amazing when you think about it.”

-By Janet Davison, CBC News