Greenpeace Arctic 30: 2 Canadians jailed in Russia

Last week, when Russian authorities moved the 30 Greenpeace activists they had arrested nearly two months earlier, Canadians Paul Ruzycki and Alexandre Paul ended up sharing a cell in the prisoner train car, along with another activist.

Despite the cramped conditions, Ruzycki wrote to his family that it was a special time, with “good energy.” Until then, the 30 activists had been kept separate.

They were all being moved from the jail in Murmansk, a port in the Russian Arctic, to different prisons in St. Petersburg.

On Sept. 18 – two months ago today – two Greenpeace activists had tried to scale Gazprom’s Prirazlomnaya platform and unfurl a banner, to protest oil drilling in the Arctic Ocean.

The next day, while waiting in international waters for the anticipated release and return of those two, the other 28 people on board the Greenpeace ship Arctic Sunrise, including the two Canadians, were arrested at gunpoint by Russian forces.

Greenpeace is pushing for the so-called Arctic 30 to be released on bail while awaiting trial. But Russian authorities are now asking that the prisoners be held for another three months while they continue to investigate. They face Russian charges of “hooliganism.”

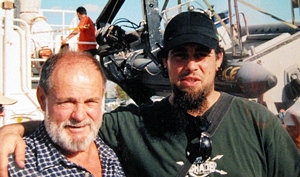

Paul Ruzycki, 48, is from a large family with five siblings in small town Ontario and Alexandre Paul, 36, is an only child from Montreal. On the surface, they don’t seem to have much in common, except for their commitment to the environment, and now the fact that they have spent almost two months in Russian jails.

Paul Ruzycki

Ruzycki is the chief mate on the Arctic Sunrise, the second in command, and is a long-time seaman who has been involved with Greenpeace for 25 years.

Born in 1965 in Port Colborne, Ont., the youngest of six children, he was a seaman on the Great Lakes before joining Greenpeace.

Ruzycki’s father Frank, an electrician, served in the navy during the Second World War, and, until his death in 1993, he kept a scrapbook of Paul’s adventures with Greenpeace, clipping every article he could find. Now Paul keeps his father’s navy ring with him while on Greenpeace missions.

Family members told CBC News that Ruzycki developed an early concern for the environment after a stint with Katimavik, the Canadian volunteer service for young people.

The story goes that when his ship was in the middle of Lake Erie, he was ordered to throw overboard a bunch of paints and other hazardous materials, and when he refused he was fired. He was about 22 at the time, his family recalls.

An older sister, Patti, was already a long-time Greenpeace supporter, and says she was the one who suggested Paul look into joining the environmental group.

Volunteers for Greenpeace

Ruzycki began with Greenpeace as a deck hand and then a welder, constantly trying to upgrade his skills.

In January, he did his chief mate’s oral exam in Toronto.

Marine safety inspector Murray Helwig administered the test and he says Ruzycki stood out from the other seaman he usually encounters.

“You don’t meet seaman like that anymore,” Helwig said.

At first, Helwig thought of Ruzycki as “an old hippie,” although he quickly learned “There’s a lot more to Paul than that,” and calls him things like “an outstanding citizen,” “a sincere guy,” and “principled.”

Helwig also recalls that when he first inspected the Arctic Sunrise a few years back, it “looked pretty rough, so Paul’s a brave guy to work on a ship of that calibre.”

Ruzycki’s sister Debbie Reid says that Paul “studied his brains out trying to get to the position he’s in now.”

Reid says the family followed every voyage that Ruzycki took and that, when he wasn’t on Greenpeace missions in the fifteen years after his father died, he helped look after their ailing mother.

The cool uncle

“If you were ever in trouble,” Reid says, “he is the person you would want to call, because he has a clear head, he’s a logical thinker, he doesn’t get frazzled.”

Ten years younger than his sister, Ruzycki was like an older brother to her kids, “the cool uncle, they always wanted to do everything he did.”

Reid’s son Jesse, now 36, also joined Greenpeace and he says: “It seemed like the coolest thing, what he was doing and the whole family was super, super proud of him and I set my sights on that when I was about 11, saying that’s what I’m going to do.”

Jesse’s first Greenpeace action was with Paul in 1995 in Ottawa on a boat on the Rideau Canal. They held a banner when a delegation from China was there in protest against a CANDU nuclear reactor deal.

He describes his uncle as “very peaceful, committed and honorable” and “one of the most important people I have in my life.”

From his cell in Jail Number Four St. Petersburg, on Nov. 13, Ruzycki wrote to his family, “All I can do is hope for tomorrow.” Ever the sailor, he told them that for the first time in 49 days he’d seen the moon, watching its rise through the bars on the cell window.

Alexandre Paul

For Alexandre Paul, his Greenpeace connection came before his environmentalism and his seafaring.

Paul was born in 1977, the son of a fireman and a nurse in the Hochelaga-Maisonneuve district in east Montreal.

His mother Nicole says that for high school, they sent Alexandre to the private Collège Notre-Dame du Sacré-Cœur in the wealthy neighbourhood of Outremont to get him out of his own rough neighbourhood. He went on to study at a CEGEP but his father Raymond says he was “not so good at school.”

He had been working in restaurant kitchens and bars in Montreal, including as a doorman, when he saw an ad in the Journal de Montreal in 1998 that Greenpeace was hiring door-to-door canvassers.

Nicole says it was a good job for her son, who she describes as sociable and someone with a talent for talking to people.

“From that he developed an interest in environmental issues,” she said.

The man who hired him was Vic Thibert, then the assistant manager at the Greenpeace office in Montreal and now the fundraising manager for Quebec. Thibert and Paul became friends and they ended up sharing an apartment for about three years.

A ‘gentle giant’

Thibert describes Paul as “a fun guy to be around, who likes to laugh” but who is also very smart, dedicated, a “non-violent, gentle giant who wouldn’t hurt a fly.” Thibert says he reads a lot but also likes comedy and zombie movies.

Nicole adds that her son is “a fellow of passions.”

Paul once said about the canvassing job, “At least people who sell brooms have something in their hands; we have a concept.”

Paul worked as a canvasser for about three years, but had scaled back the canvassing to part-time when the Arctic Sunrise docked in Montreal in 2005. Thibert says Paul did some volunteer work on the ship and when it sailed he was part of the crew as a volunteer deckhand for the three-month voyage.

He sailed with the ship once more as a volunteer before it became a (poorly) paid job.

In 2006, he was a member of the Arctic Sunrise crew that blockaded a ship in an Estonian port that had returned to Europe after dumping a load of particularly deadly toxic waste in Ivory Coast.

For this mission, Paul worked as the boatswain, which means he was in charge of supplies.

Nicole was worried during Paul’s first voyage but until the Russian seizure, this mission attracted no particular concern from her or other family and friends contacted by CBC News.

“Alexandre was always aware that he could end up in prison with these kinds of actions,” Nicole said.

He’d been arrested once before. From his too few calls and letters, she surmises that “He doesn’t sound too worried, he sounds like he’s making friends.”

While still in Murmansk, he told her that he was sharing his cell with a local Russian, an orphan receiving no family support and destitute, so Alexandre was sharing his supplies with him.

Thibert, once again flatmates for the few months a year Paul is in Montreal, said his friend’s morale sounds pretty good under the circumstances, that he even joked about the weight he’s lost because of the appalling jail food.

Paul himself writes, “I’ll stay strong, I won’t despair.”

“We have nothing against Russia, as a matter of fact; we did this for them and their children.”