Ocean mapping leads to new ship route in Canadian Arctic

Ocean mapping efforts in Canada’s Arctic have uncovered a new passage for increasing shipping traffic to Iqaluit, the capital city of Canada’s eastern Arctic territory of Nunavut.

The isolated region receives most of its supplies through shipping so the discovery of the new shipping highway, due in part to New Brunswick-based researchers, is significant.

“It’s a much better approach to Iqaluit,” says Weston Renoud, a masters student in hydrography at the University of New Brunswick. “It’s a deeper and wider approach. This is great for shipping.

“The existing channel is fairly narrow and shallow, so only one vessel can go through at a time, and it has to be timed for the right tide,” he says.

“Much like the Bay of Fundy, Frobisher has quite extreme tides,” explains Renoud. “We often treat the ocean’s surface as a flat surface, but tides can mean you’re a lot lower going into an area than you are coming out of it. It’s always changing.”

The new passage allows for two ships to pass in opposite directions and can by used by multiple ships at one time.

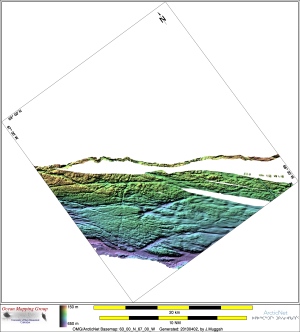

The discovery is due, in part, to the increased effort by the Ocean Mapping Group, based out of UNB in Fredericton, to chart the ocean floor in Canada’s developing Arctic.

The new route is subject to verification by the Canadian Hydrographic Service, the authority on the country’s nautical charts and navigation. It will review OMG’s data for any safety concerns and publish the route if it is approved.

The group is part of a coalition that includes the Nunavut government, the Canadian Hydrographic Service and the ArcticNet Network of Centres of Excellence that is focused on expanding the knowledge of what exactly lies at the bottom of some of Canada’s coldest bodies of water.

Thawing allows for first surveys

Some of the areas being surveyed include areas where the waters of the Arctic are thawing for the first time in the modern era.

“With the ice melting off further and further each summer there is a lot of interest to get access to places that people have previously never been around,” says Renoud.

“This includes shipping, but also oil and gas exploration. There’s more traffic up there than ever before.”

The mapping methods require the use of global positioning systems and multibeam echosounders which ping the ocean floor. Sound-waves are directed towards the ocean bottom and the amount of time that it takes for an echo to bounce back is recorded and used to build a map.

Water density, salinity, and temperature are factored in to build an image of the underwater mountain ranges, deep valleys and other geographical features. The topography under the sea is just as varied as it is on land.

Unlike terrestrial mapping, ocean mapping also has to factor in the ever-changing tides. It adds an extra dimension to mapping a given area.

“We’ve only now got GPS techniques that give us accurate reading on how high above the sea floor we actually are,” says Renoud. “It’s a lot harder given that you’re always on a boat. Plus you’re always bobbing up and down.”

Accuracy in this new dimension of mapping is critical. Being a metre off can mean the difference between a ship getting to Iqaluit safely, or running aground with an entire community’s supplies.

“Not only are we mapping, but we’re building a system so a mariner can look at our data and tell how much water is under him,” says Renoud.

Canada’s ocean mapping has recently been touted on an international scale as the country looks to stake a claim in a large expanse of previously undeclared ocean floor, including the claim to the North Pole.

“There’s a lot of sea floor,” exclaims Renoud. “In total, we’ve barely done a fraction.”

-By Shane Fowler, CBC News

Related Links: