Blog: At White House, U.S. and Nordic leaders talk shop on the Arctic

Last Friday, over a state dinner of cured salmon, salt-cured ahi tuna, and venison tartar with truffle vinaigrette, President Barack Obama hosted leaders from the Kingdom of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden.

Prime Minister Lars Lokke Rasmussen (Denmark), President Sauli Niinisto (Finland), Prime Minister Sigurdur Ingi Johannsson (Iceland), Prime Minister Erna Solberg (Norway), and Prime Minister Stefan Lofven (Sweden) all gathered around to enjoy a meal cooked by Swedish chef Marcus Samuelsson.

Earlier in the day, Obama and the Nordic leaders discussed issues pertaining to security and defence, migration and refugees, climate, energy and the Arctic, and economic growth and global development. They released a fact sheet and a lengthy joint statement summarizing their views. The joint statement did not express anything particularly novel about the Arctic, instead making vague gestures towards the importance of ecosystem-based and precautionary approaches, scientifically-based conservation, and the importance of indigenous and local knowledge.

The statement also acknowledged the Manichean nature of the Arctic as a region of both vulnerability and opportunity. On the one hand, climate change is threatening indigenous ways of life, but on the other hand, the region is rich in industrial opportunities like transport and energy, as the excerpt below notes:

“The Arctic is rapidly changing and attracting global attention. It is a globally unique region that provides livelihoods for its inhabitants, but is also one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change. Rich with opportunities for transport, tourism, energy, and innovation, the Arctic is characterized by close cooperation on a broad range of issues between the United States and the Nordic Countries, together with our Arctic partners Canada and Russia.”

The joint statement, however, did not explain that climate change makes possible these opportunities, nor did it detail how their pursuit could actually exacerbate Arctic warming and melting. The notion of this so-called “Arctic paradox” has gained currency in Arctic conference circles, but it hasn’t yet made the leap to the pages of White House joint statements.

And while outlets like the Washington Post and EcoWatch claim that now, following the summit, “Economic activity in the Arctic must pass climate test,” it just isn’t clear from the blanket language of the statement how this is going to be achieved – especially given the irony of Norway’s Goliat oil field in the Barents Sea, the northernmost in the world, opening almost exactly one month prior to the signing of the U.S.-Nordic joint statement.

Maritime Executive reports that at the Goliat oil field, “for the first time in Norway, the local fishing fleet is a permanent part of the oil spill preparedness organization.” One can imagine a watery future in which all of the fishermen who are unable to fish in an ice-free Central Arctic Ocean due to a preemptive measure signed last year are instead employed in the service of oil rigs anchored in place where icebergs once floated. Meanwhile, the Arctic states will continue issuing statements about how Arctic economic activity must be sustainable.

The 2016 U.S.-Nordic joint statement can also be compared to the one released by the same six countries in 2013. The same boilerplate is again issued about the Arctic environment, sustainable development, and indigenous peoples, though with an added focus on clean energy and climate finance. But notably, Russia is not once mentioned. The 2013 statement was released in September, a few months before protests kicked off in Ukraine’s capital, Kiev.

Some things change (Russia), some things stay the same (the Arctic).

O Canada

The U.S.-Nordic joint statement follows on the U.S.-Canada joint statement released in March in concert with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s state visit. Compared to the bilateral U.S.-Canada joint statement, the U.S-Nordic joint statement is more concerned with international cooperation in the Arctic. This makes sense given the more multilateral nature of the U.S.-Nordic meeting.

In contrast, the U.S.-Canada joint statement was much more detailed than the Nordic one, and it outlined four objectives for future Arctic leadership across global, regional, and notably local scales:

- Conserving Arctic biodiversity through science-based decision making

- Incorporating Indigenous science and traditional knowledge into decision-making

- Building a sustainable Arctic economy

- Supporting strong Arctic communities

Under the “strong Arctic communities objective,” an unusual amount of attention is paid to issues that often go ignored in international meetings about the Arctic such as the lack of housing for indigenous peoples and indigenous mental health. The U.S.-Canada joint statement proclaims:

“With partners, we will develop and share a plan and timeline for deploying innovative renewable energy and efficiency alternatives to diesel and advance community climate change adaptation. We will do this through closer coordination among Indigenous, state, provincial, and territorial governments and the development of innovative options for housing and infrastructure. We also commit to greater action to address the serious challenges of mental wellness, education, Indigenous language, and skill development, particularly among Indigenous youth.”

By the numbers

How do the three statements – the Joint Statement by the Kingdom of Denmark, Republic of Finland, Republic of Iceland, Kingdom of Norway, Kingdom of Sweden, and the U.S. in 2013, the U.S.-Nordic Leaders’ Summit Joint Statement in 2016, and the U.S.-Canada Joint Statement on Climate, Energy, and Arctic Leadership compare side by side?

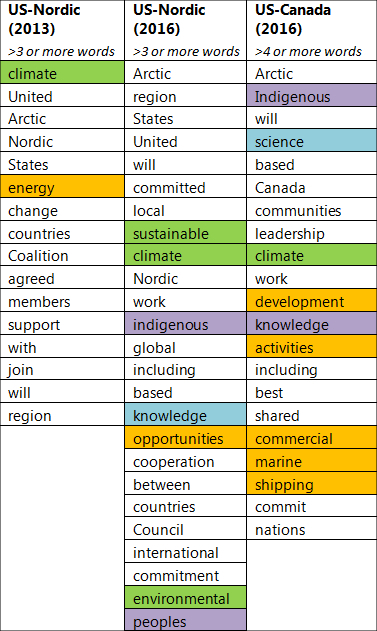

I quickly generated a script in Python to run a rough textual analysis of the three statements, looking specifically at the sections within each one that focus on the Arctic. This script then found the most common words used in each statement. The table is colour-coded with green cells referring to environmental issues, orange to development, purple to indigenous peoples, and blue to knowledge and science.

Whereas the Canadian statement pays the most attention to Indigenous peoples (with a capital “i”) and development issues, the statements with the Nordic countries over the years focus more on energy, climate, and sustainability. These discursive contrasts correspond with the difference between the Nordic countries’ priorities as chairs of the Arctic Council – generally climate change and the environment – and those of the Canadian chairmanship, which promoted “Development for the People of the North.”

Russia: a state of exception?

The U.S. has now released joint statements that touch upon the Arctic with all but one Arctic state: Russia. President Vladimir Putin also remains the Arctic’s only leader to not be feted by a state dinner under the Obama administration, a fact which will probably not change before he leaves office. The U.S.-Nordic summit state dinner – the twelfth of the Obama administration – was preceded in March by a state dinner in honour of the visit of Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau (where guests feasted on Yukon potatoes and maple pecan cake).

Although the Arctic remains a relative bright spot in cooperation between Russia and the West, the U.S. and Nordic leaders took the opportunity to call out Russia in the joint statement:

“The United States and the Nordic countries share a firm conviction that there can be no compromises over the international security order and its fundamental principles. Russia’s illegal occupation and attempted annexation of Crimea, which we do not accept, its aggression in Donbas, and its attempts to destabilize Ukraine are inconsistent with international law and violate the established European security order.”

The statement additionally chastised Russia’s behaviour in the Baltic Sea:

The United States and the Nordic countries are concerned by Russia’s growing military presence in the Baltic Sea region, its nuclear posturing, its undeclared exercises, and the provocative actions taken by Russian aircraft and naval vessels. We call on Russia to ensure that its military manoeuvres and exercises are in full compliance with its international obligations and commitments to security and stability.

The Washington Post also criticized Russia, arguing, “The communique the group will issue comes a month and a half after the United States and Canada agreed to impose a similar litmus test on future Arctic activities, meaning that Russia now stands as the sole nation that has not agreed to integrate these standards as a matter of routine policy.”

While Russia may not have integrated these supposed standards as policy, at the end of the day, Russia, the U.S., Canada, Norway, and Iceland all have pursued offshore oil to some degree – and to sometimes horrendous standards, as the disaster of Shell’s Kulluk oil rig in offshore Alaska revealed. At least with Russia, we can say that the country puts its money where its mouth is. For that reason and many others, don’t expect borscht and caviar on the menu at the White House any time soon.

Russian oil platform in the Arctic Ocean.

Photo credit: Krichevsky. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

This post first appeared on Cryopolitics, an Arctic News and Analysis blog.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Obama, Trudeau announce plans to fight Arctic oil and gas pollution, Alaska Dispatch News

Finland: Japan, Finland agree to boost cooperation in the Arctic, The Indpendent Barents Observer

Iceland: Nordic countries discuss closer defense cooperation, The Independent Barents Observer

Norway: Arctic Council aims to boost business, Barents Observer

Russia: Japan wants more Arctic cooperation with Russia, Barents Observer

Sweden: Arctic Council – From looking out to looking in, Blog by Mia Bennett, Cryopolitics

United States: Arctic remains refuge of friendly US-Russia relations, Alaska Dispatch News