Control or ban? International discussion on commercial fishery in the Arctic Ocean

Arctic states and several other invited fishing nations met in Iqaluit, Nunavut, Canada, to continue discussions on regulation for commercial fishing in international waters of the High Arctic. There was no final agreement, but “good progress” was apparently made.

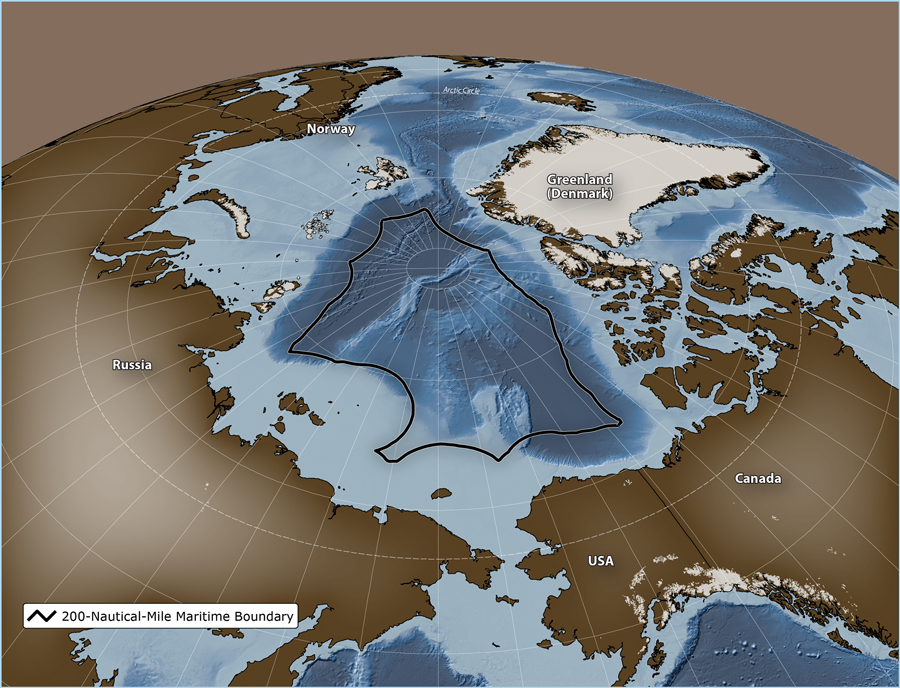

Never an issue before because of year-round ice cover, global warming means large areas of the huge Arctic Ocean, considered international waters, are now navigable in summer months and potentially available to factory fishing trawlers.

Alex Speers-Roesch is an Arctic campaigner with Greenpeace Canada and talks about the nature of the discussions.

The meeting two weeks ago (July6-8) involved delegations from Canada, China, Denmark for the Faroe Islands and Greenland, the European Union, Iceland, Japan, South Korea, Norway, Russia and the United States.

Scientists have long said no commercial fishing should be done until more is known about the species that are in the Arctic Ocean’s international waters, the population levels, and their ability to recover from commercial fishing catches, i.e., sustainability levels.

Although the five Arctic nations, including Canada, have agreed to a temporary moratorium, the meeting seems to be moving toward developing international controls to allow, but regulate, an eventual commercial fishery in the previously inaccessible Arctic Ocean.

It follows previous meetings of February 2014 in Nuuk Greenland, and another in Oslo Sweden in July 2015, another in December, and yet another in Washington in April of this year

A brief statement from the chairman of the gathering after the Iqaluit meeting said the meeting made, “good progress in resolving differences of view on a number of main issues under discussion. There was a general belief that these discussions have the possibility of concluding successfully in the near future”.

Binding, non-binding, monitoring?

Of concern is whether an eventual agreement would be binding or non-binding on participant states.

However, Speers-Roesch says the states all seem to be of the opinion that if a fishery can be established, it should be established.

He also says a non-binding agreement really means very little in terms of regulating an eventual fishery.

Another concern is that even with an eventual binding agreement on things like quotas, there is virtually no way to verify that regulations would be adhered to by the various signatory nations.

Greenpeace meanwhile is of the opinion that the Arctic Ocean is a unique ecosystem that should be preserved in its current natural state as a marine sanctuary protected from any and all extraction processes ranging from fishing to oil, gas, and mineral exploitation.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Is a fishing boom in the Arctic a sure thing?, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: EU drops seal-protection complaint against Finland, Yle News

Greenland: The donut hole at the centre of the Arctic Ocean, Blog by Mia Bennett

Norway: Climate change will lead to ecosystem clash, Barents Observer

Sweden: Record numbers for Swedish wild salmon, Radio Sweden

Russia: Oryong 501 sinking highlights Arctic fishing, shipping issues, Blog by Mia Bennett

United States: Ice retreat threatening Bering Sea pollock, Alaska Public Radio Network