Alaska’s heroin problem brings together state, local and federal leaders in search of a solution

BETHEL — Alaska’s heroin problem is significant, growing and, authorities say, in need of attention from all quarters to get under control.

That was the message Monday at school and community meetings in Bethel that included Alaska’s top FBI agent and a federal prosecutor, local police and a state trooper, a pharmacist and a counselor, public health nurses and Native hospital leaders.

A team is touring rural Alaska this month to put attention on the damage heroin and other opioid drugs already are inflicting across the state. The Obama administration has declared a nationwide “week of action.” The hope, say leaders, is to prevent young people from falling under the grip and to steer those already addicted toward help.

Some wonder whether the national anti-opioid agenda is the right strategy for the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, where alcohol causes so many more problems.

The destruction of the addictive drugs showed itself in the Southwestern Alaska village of Quinhagak last month when a 19-year-old just out of high school died and three others overdosed on heroin supercharged with the painkiller fentanyl.

[After a young woman’s death from a heroin overdose, an Alaska village looks inward]

Disturbing first-person accounts

A team that includes Marlin Ritzman, the Anchorage-based FBI special agent in charge, and Andrea Hattan, an assistant U.S. attorney, already traveled to Kotzebue, Barrow and Bethel and were in Ketchikan on Tuesday. Nome, Kodiak and Petersburg are scheduled for visits, too.

Community meetings and school assemblies on heroin and other opioids are anchored by a film produced by the FBI and the Drug Enforcement Administration called “Chasing the Dragon: The Life of an Opiate Addict” that features disturbing first-person accounts by drug users and their family members.

One mother, Trish, tells of helping to put her daughter — once a bubbly honor-roll student — in jail as a way to get her clean. Six days after getting out, Trish found her daughter in her room, dead of a heroin overdose.

“Still calling her, still calling her. It’s that powerful that you could spend seven months clean, clean and being educated on nothing but how to beat it, how bad it is for you,” Trish says in the film. “And you last six days.”

Addicts talked about injecting with heroin cut with meat tenderizer, which then ate away at their flesh. They just kept doing it. A woman said maggots multiplied in an infected leg wound from where she had stuck the needle in. One time, she ended up in the hospital and walked out to buy heroin, still in her hospital gown. She used the IV line to shoot up.

Cory, a young man, talked about growing up in a good family, camping, becoming an Eagle Scout. Then, he said, his fixation on drugs turned him into a monster. He lost years in his addiction fog.

Addressing schools

Similar stories unfold right in Bethel, Teri Forst, a counselor at Bethel Family Clinic, told students at the Bethel Regional High School morning assembly.

“A lot of you may be thinking they just show the scariest, the worst, the most dangerous, the worst-case scenarios,” said Forst, who grew up and went through school in Bethel. “I can tell you I’ve seen dozens of clients in my office with that exact same story that are from this town that you each of may know and love. So that’s for real.”

Kids often fidget and squirm their way through school assemblies. For Bethel’s assembly on heroin, hundreds of students sat quietly, watching and listening.

“Please, please, please take this movie seriously,” Forst urged.

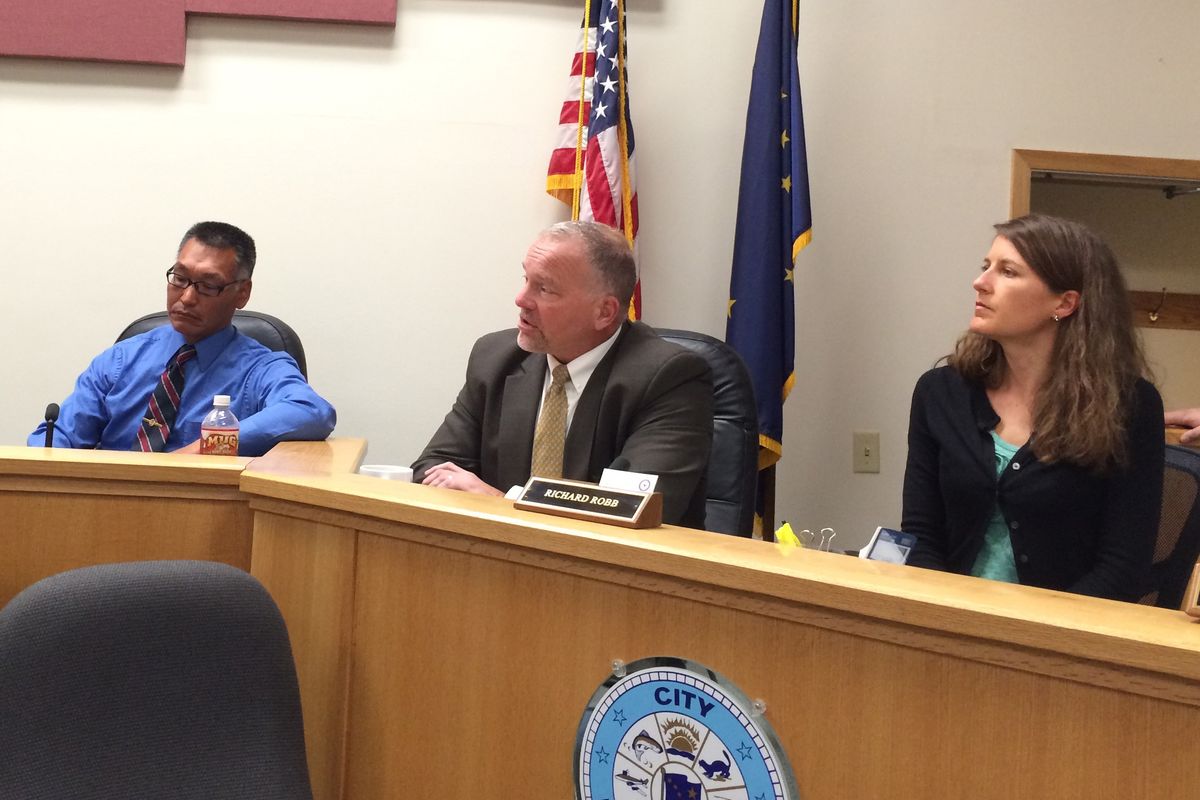

Later, an overflow crowd packed the Bethel City Council chambers at City Hall for a similar showing and panel discussion.

Alaska’s rate of death from heroin is 50 percent higher than the national average and from prescription opioids, double it, Hattan, the federal prosecutor, told the high school and community groups. And the numbers are growing, she said.

[Alaska’s heroin death rate spikes, but prescription opioids take more lives]

Medical community & painkillers

Both the high school students and the community residents asked pointed questions. Why do doctors prescribe painkillers if they are so addictive — and lead some to heroin? What are police doing? What can residents do with unused pain pills? What help is available?

Michael Stamper, a pharmacist with Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corp., said painkillers have a place in medicine, but must be carefully controlled.

“As low a dose as possible for as short a time as possible,” he said.

Patients are put on pain management contracts, and a committee that includes medical providers, behavioral health clinicians and pharmacists reviews them monthly.

Asking for public’s help

Law enforcement needs the public’s help, said Bethel Police Chief Andre Achee. If you see something, call and keep calling, he said. If something suspicious is happening right then, stress that to the dispatcher, the chief said.

Jerry Evan, an investigator with Alaska State Troopers’ Western Alaska Alcohol and Narcotics Team who is originally from the Kuskokwim River village of Napaskiak, told the community anonymous tips may not be enough to get a search warrant. Drug cases are complex, not cut and dried like drunken-driving offenses, he said. The Western Alaska team is down to two investigators, when it used to have three and a clerk, he said.

As to unused prescription pain pills, residents can mix them with coffee grounds or kitty litter, and put them in the trash, Stamper said. People also can bring them to troopers, or ask troopers to pick them up, Evan said. Don’t flush them down the toilet, Hattan said. Drugs can end up in water sources and waterways, including the Kuskokwim River.

Some elements of the local response are in flux. Officials with Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corp. last week said the antidote naloxone would be provided to users and their families over the counter, without a prescription. It can revive people near death from a heroin overdose.

Asked about naloxone or Narcan, the brand name, at Bethel’s community meeting, YKHC pharmacist Stamper said a prescription would be needed.

After the meeting, Dan Winkelman, chief executive of the Alaska Native-run health corporation, said he had been told the facility would provide it over the counter, “and if we can’t, that will be changed immediately.”

New program

Community members also were told YKHC will begin offering treatment specifically for heroin addiction this fall but were told first it would be outpatient, then it would be residential.

The new program is designed as intensive outpatient but some patients who need residential treatment will be able to get it, based on an assessment, Jim Sweeney, YKHC vice president, explained after the meeting.

The spotlight on heroin and opioid abuse is welcome. Yet alcohol leads to far more deaths, injuries and arrests, Leif Albertson, a Bethel City Council member and a paramedic with the Bethel Fire Department, noted after the meeting.

“As a volunteer on the ambulance, I have seen the same thing; call after call for alcohol-related injury, incapacitation or death,” Albertson said in an email. “In the fight against substance abuse, we need to remember that alcohol has a near-monopoly on the suffering we see in our region. If we’re serious about addiction in our community, we need to be honest about that fact.”

That’s a fair point, Jay Butler, the state’s chief medical officer, said Tuesday. Alcohol has not received the same focused public health response as heroin and prescription opioids, Butler said, even though it is a more pervasive problem.

The recent rise in deaths from heroin and opioids and the availability of an antidote for someone who has stopped breathing from heroin are among the reasons those drugs get such attention, he said.

“In some ways the opioid epidemic suggests it may have more opportunities for intervention and to reverse the current trends of what we are seeing in deaths,” he said.

Still, as for heroin, alcohol abuse materializes as a public health problem as well as a problem for individuals, he said. More attention is needed for alcohol as well, he said.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Canadian Inuit release suicide prevention strategy, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Finland’s unacknowledged problem – alcoholism, Yle News

Russia: Why high suicide rates in Arctic Russia?, Blog by Deutsche Welle’s Iceblogger

Sweden: Gender stereotypes behind high suicide rate, Radio Sweden

United States: Alaska’s perspective on heroin addiction, Alaska Dispatch News