What ‘young’ Arctic rocks tell us about origins of the Earth and Moon

Volcanic rocks from the Canadian Arctic are changing what scientists think about the origins of the Earth and the Moon, says Hanika Rizo.

The 33-year-old Mexican-born geologist at Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) says her research into unusual concentrations of the tungsten-182 isotope in “young” 60-million-year-old rocks found in Nunavut is helping to rewrite the early history of our planet and its largest satellite, which were formed about 4.5 billion years ago.

“I’ve been working for a while with old rocks, when I say old, they were formed 3.8 billion years ago, and recently I got interested in modern rocks from 60 million years ago,” said Rizo who teaches at UQAM’s department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences.

“I got interested in these rocks because studies that were performed on these rocks were suggesting that these rocks were bringing up information from very deep inside the Earth, deeper than 2,000 kilometres under our feet.”

Information from deep in the mantle

Rizo studies these “weird” tungsten-182 isotopes that were created very early in the planet’s history to try to figure out how old parts of the inside of the Earth were.

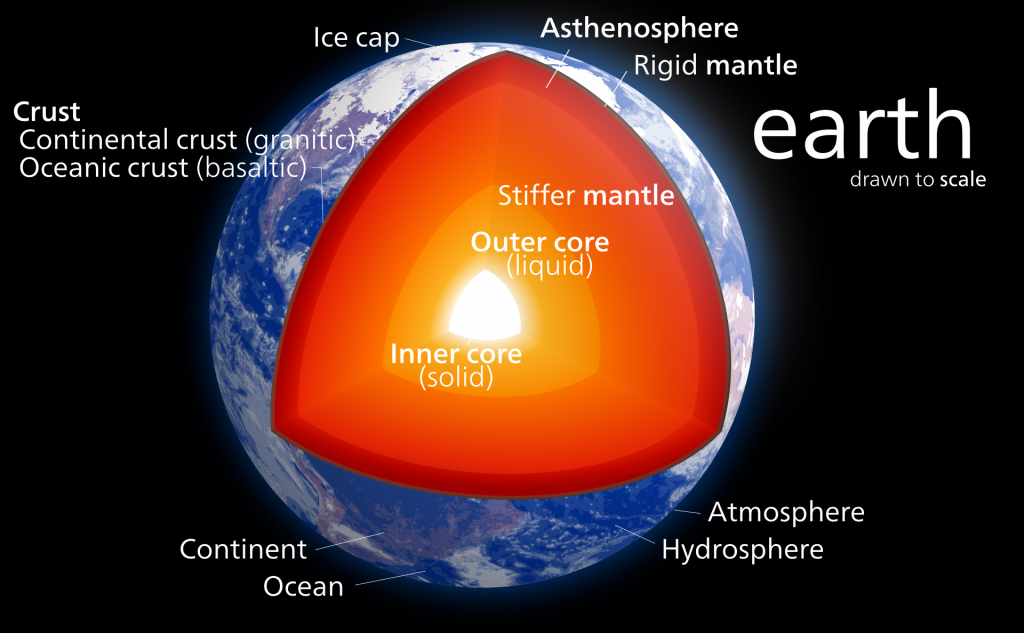

“These rocks were brought up from the mantle,” Rizo said. “If you look at the cross-section of the Earth, we have the continents, which are a thin layer under our feet, they can be 20 to 60 kilometres [deep]. If you go deeper, you get into the mantle, which goes all the way until 2,900 kilometres. And then we have the core which is made of metal and has two sections one that is liquid and one that is solid.”

(Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0)

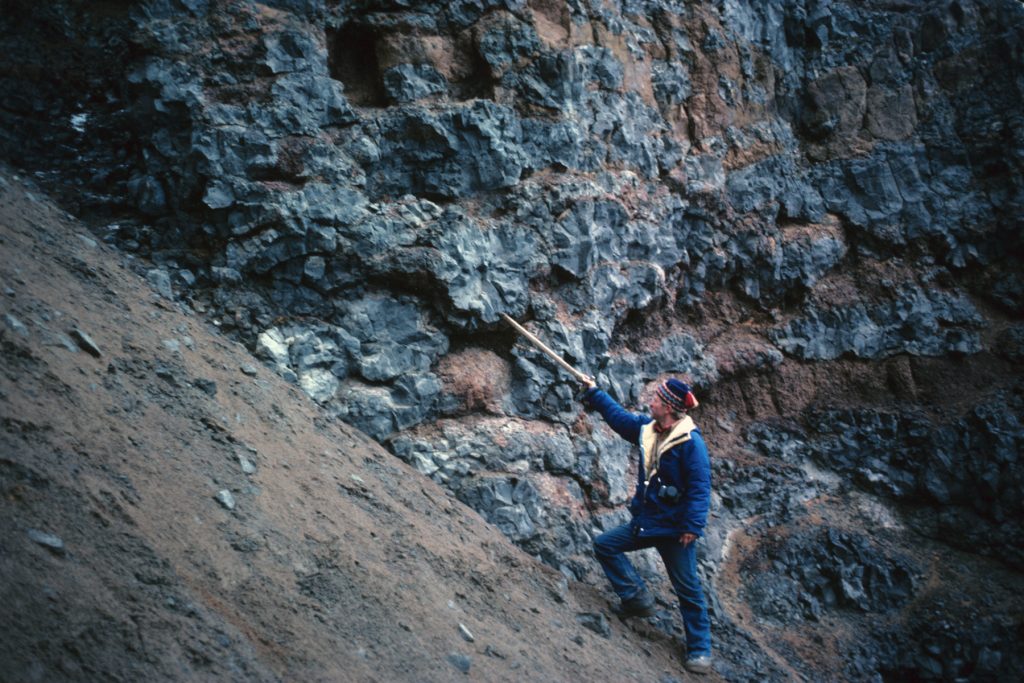

The rocks Rizo studies were collected in southeastern Baffin Island in Nunavut by McGill University researcher Don Francis, professor emeritus at the university’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

“These rocks are volcanic, so they were lavas that solidified and these volcanic rocks are very particular because they were emplaced after volcanic eruptions that were huge, very voluminous, a lot of lava was brought up by these volcanoes,” Rizo said. “These are what we call flood basalts, they are produced by volcanic eruptions that we have never seen in human history.”

Researchers believe these volcanic eruptions brought up materials from the deep parts of the mantle.

Young rocks with an old story to tell

And parts of Baffin Island were built through this emplacement of flood basalts that have very deep sources, Rizo said.

“These rocks even if they’re young, they have chemical signatures that suggest that part of the mantle where they come from are extremely old,” Rizo said, “so old that these parts we think were formed during what we call the accretion of our planet.”

Planetary scientists theorize that planets formed through the process of accretion or collision of different bodies – dust, rocks, and small planetoids – in the proto-solar nebula. Initially this early mass was extremely hot, like a ball of molten lava. The heavier elements such as iron and nickel in this liquid ball sank and formed the core while lighter elements such as silicon floated up, creating the mantle.

For a long time scientists believed that these early parts of the planet were mixed beyond recognition by the various forces inside the Earth, Rizo said.

“But it happens that these rocks have told us that there still parts inside the Earth that were formed during the very first moments of our planet formation and have resisted being remixed by mantle convection or plate tectonics,” she said. “The idea of thinking that we have old parts inside the Earth that can give us information about how our planet was formed is incredible.”

Moreover, these rocks can give us information not only about our planet but also about how the Moon was formed, Rizo said.

Rewriting the Moon’s history

The most accepted hypothesis about the origins of the Moon is that it was created through a giant impact, Rizo said.

“This giant impact should have melted big portions of the Earth, maybe the whole mantle,” Rizo said. “The idea up to a couple of years ago was that an asteroid of the size of Mars hit the Earth and then the debris after this collision got trapped in the gravity of our planet and then came together to form the Moon.”

But the analysis of the chemical composition of the rocks found in southeastern Nunavut is changing that view.

“Finding parts of the mantle that haven’t melted because of this impact tell us that this giant impact wasn’t as giant as we thought,” Rizo said. “But maybe, just a smaller object, smaller than Mars that hit the Earth but rather with a very energetic way.”

The analysis of these rocks allows researchers to answer questions about how the Earth is working today and how it formed billions of years ago, Rizo said.

Rizo’s research paper Preservation of Earth-forming events in the tungsten isotopic composition of modern flood basalts was published in the prestigious Science magazine in May 2016.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Dreams made of diamonds, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Puzzling migration fluke brings thousands of Siberian birds to Finland, Yle News

Greenland: New model predicts flow of Greenland’s glaciers, Alaska Dispatch News

Norway: New report sees Arctic melt on course to tip global climate, Deutsche Welle’s Iceblogger

Russia: Ancient virus found in Arctic permafrost, Alaska Dispatch News

Sweden: Swedes help in hunt to locate oldest ice on Earth, Radio Sweden

United States: Arctic soils are set to release a lot of carbon – probably more than local plants can absorb, Alaska Dispatch News