Growing deer population leading to more accidents, property damage in Finland

The population of wild white-tailed deer has skyrocketed in Finland over the past two decades, leading to a rapid increase in accidents and property damage.

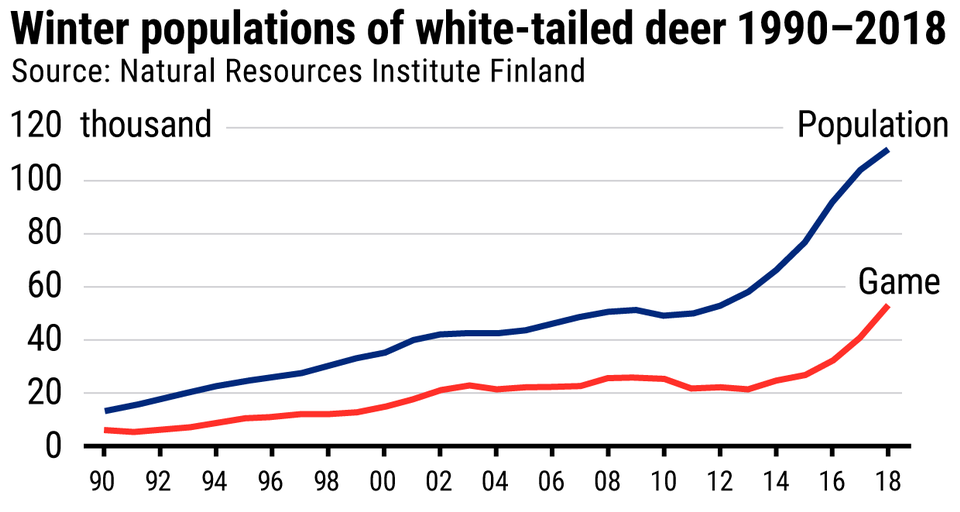

The Natural Resources Institute (Luke) estimates that the country’s population of the non-native deer species has quadrupled to some 111,000 individuals in 20 years.

The animals are known to cause losses to gardens and plantations by eating crops such as apples and rummaging through human garbage and other outdoor property.

However, the gravest danger posed by the rise in deer is an increase in auto collisions. Statistics Finland reports that more than 6,200 traffic accidents involving deer occurred in 2018, over 1,000 more than the previous year.

Some in Finland are becoming agitated by the harm caused by the species, taking to social media to complain about damage to gardens, for instance.

“If public sentiment like this starts to become more common, it means that people are nearing the end of their tolerance for the phenomenon,” said researcher Jyrki Pusenius from Luke. “Deer populations are certainly too dense in a number of habitats; you can see it in the condition of wild blueberry bushes.”

Culling enforced, advanced mapping developed

At its densest, populations of white-tailed deer can number more than 50 per 1,000 hectares. In comparison, Finnish populations of elk (closely related to North American moose) have a maximum target denseness of just three animals per thousand hectares.

In an effort to literally cull the herd, the government issued some 30 percent more hunting licenses for deer this year compared to 2018 – to a record-breaking 58,000 or so in total. A single permit allows a hunter to fell either one adult deer or two fawns.

However, while shooting the creatures is effectively the only way to halt runaway population growth, more accurate information on population sizes is also sorely needed. Luke said its estimates are trustworthy, but they come with a five-percent margin of error.

The Finnish Wildlife Agency (FWA) has also sought methods to pinpoint populations as exactly as possible, suggesting the installation of more hunting cameras and encouraging more eyewitness reports.

Artificial intelligence may also be used to identify animals based on age and species.

“We need a population control scheme for deer like we have for elk and large carnivores,” said FWA project planner Mikael Wikström. “We’ve had good results with our targets for population density and variations in age and gender.”

Some hunters have also proposed that the current permit system should be waived for the white-tailed deer, as was done for the roe deer in 2005. No permit is needed to fell roe deer; instead a report to the FWA about a dead individual is enough.

Chair Jaakko Mattila from the hunting association of Western Orimattila said what is most important is that the populations decrease, but that the quality of the living animals’ wellbeing and environment does not.

“As hunters we have to make sure that the population stays robust without causing problems for motorists and people in general,” he said.

The white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) is originally native to North and South America, and was introduced to Finland in the 1930s by Finnish expats in the United States. The current population boom is descended from just a handful of individuals.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Caribou crossing Arctic Canada highway, but hunters asked to hold off for now, CBC News

Finland: Species of gull facing extinction in Finland, Yle News

Norway: Arctic fox’s rapid journey from Svalbard to Northern Canada stuns researchers, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Authorities in northwest Russia move to protect wild reindeer, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Poachers suspected behind dwindling wolf numbers in Sweden, Radio Sweden

United States: Unique freshwater Alaska seals require special conservation efforts, study finds, CBC News