Newfoundland & Labrador’s protective services for Inuit children get scathing review

Child protective services is not regarded as a resource, but as a source of fear.

That’s one of the jaw-dropping findings of Newfoundland and Labrador’s child and youth advocate following a review of child protection services for Inuit children in Newfoundland and Labrador, Atlantic Canada.

The strongly worded report, called A Long Wait for Change, was released Wednesday morning in Nain by Jackie Lake Kavanagh, the province’s child and youth advocate, following extensive CBC reporting on issues with protective care in Newfoundland and Labrador.

It contains 33 recommendations aimed at addressing the problem, including providing the support needed to transition to an Inuit-led child welfare system, and taking the steps necessary to ensure children retain their Inuit culture, language and values.

“We heard again and again that people perceive more resources going into sending children away from their communities than in keeping them close to home or with circles of people that know and care about them,” she wrote.

“There is an undeniable and pervasive sense of fear and mistrust of child protection authorities.”

The review calls for “bold, systemic change” done in full partnership with the Inuit.

“Inuit culture, knowledge (and) communities need to be front and centre, and part of that process,” Lake Kavanagh told CBC during an interview.

The independent review was done at the request of the government of Nunatsiavut, the Inuit region of northern Labrador, and found that Inuit children are struggling in the child protection system.

And in one of the most explosive revelations from the review, Lake Kavanagh said it’s clear to her that some Inuit children are being unnecessarily separated from their families, communities and culture.

Her review discovered many examples of Inuit people wanting to become foster parents, but the training necessary to make them eligible was not being regularly provided.

“When we know there are people in communities that are interested in being a part of the solution, but the capacity in those communities has not been tapped into, then I am really concerned that there are children that are sent away … when there are opportunities closer to home,” she said.

When the review began last year, there were 1,005 children in care in Newfoundland and Labrador, and 345 of them were Indigenous children. And of those, 150 were Inuit.

And many of those children are sent to non-Indigenous rural communities in Newfoundland like Roddickton and Englee.

Kavanagh said the current approach is not working because it’s “reactive and crisis-oriented,” and does not incorporate Inuit knowledge.

“Young people in care told us they miss home terribly, and fear losing their cultural connections and sense of Inuit identity.”

The recommendations, meanwhile, are sweeping, and would require action from the departments of Children, Seniors and Social Development, and Justice and Public Safety. It would also require a significant boost in funding.

Kavanagh, for example, is calling on CSSD to complete an audit of all incidents where children were sent away from their home community, and ensure every option for keeping the child in Nunatsiavut territory was exhausted.

“It’s important to take stock of where these children are,” she said.

The advocate also wants the department to focus more on prevention and early intervention, and explore a new model for foster care that could include placing parents and children together.

The report also recommends a review of the financial supports for Inuit children, families and caregivers to ensure they reflect the “northern Labrador reality.”

“This must include addressing prices of goods and services, as well as transportation and delivery costs,” the report states.

Problems in the system

Kavanagh acknowledged there are many dedicated people who go to work in the child protection system every day.

“[But] their hard work is not providing the needed results for these young people [because] it involves problems with the system of child protection services.”

For social workers, the advocate wants mandatory Indigenous cultural education training, improved access to clinical supervision and mentoring, and a commitment to ensure CSSD offices are appropriately staffed and equipped.

The report also calls for more incentives to improve recruitment and retention for social work positions in Nunatsiavut.

From a broader perspective, the report recommends that the provincial government work with Inuit leaders to improve housing, food insecurity and provide safe shelters for Inuit children and their families.

Hope remains: Kavanagh

Despite her grim assessment, Kavanagh said all hope is not lost.

“Many Inuit still believe that change is possible and that things can look and work differently if Inuit values, beliefs, and knowledge inform a new way of keeping children safe. There is an opportunity to make this shift now,” she wrote in her report.

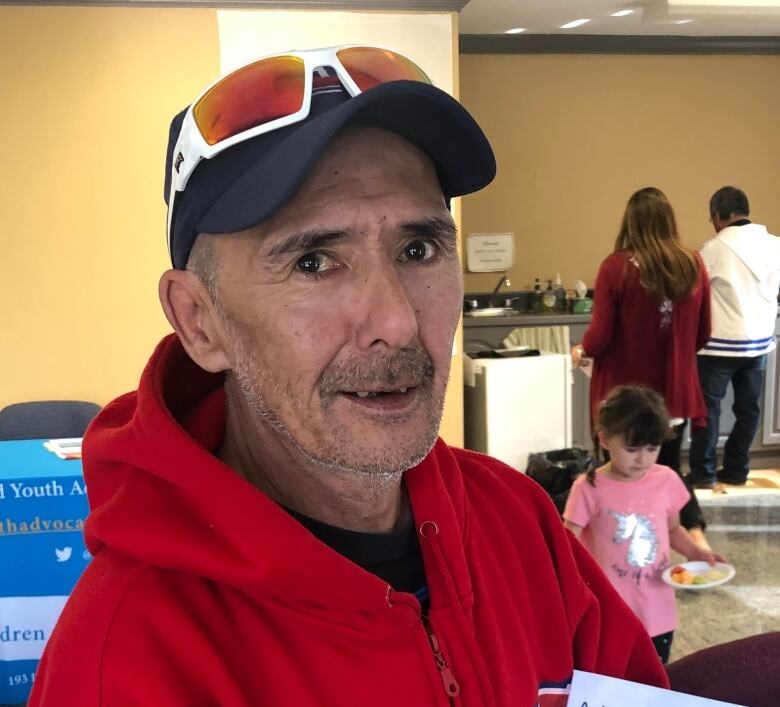

One of those encouraged by the report is Richard Leo, who had two daughters and a granddaughter placed in foster care.

Leo attended Wednesday’s release and expressed optimism that “finally someone is listening to families like myself who need to be heard and want change.”

The report does not directly recommend that Nunatsiavut establish its own child protection system, but Kavanagh strongly hints at such a system.

“This is a decision for Nunatsiavut to make on its own terms, timing, and readiness. However, there is widespread support that services and solutions for Indigenous children must be led by Indigenous governments, organizations and people.”

The final recommendation is that the province continually monitor the child welfare system, and present a report annually to the House of Assembly.

Minister says plan in the works

Meanwhile, the minister responsible for child protection services, Lisa Dempster, was also in Nain on Wednesday. She said her department’s commitment to children and families is unwavering.

“We share the goal of improving the experience and outcomes of Inuit children, youth and families,” she said.

Dempster said her department will analyze the recommendations and develop a plan, noting the new Children, Youth and Families Act, which came into effect in June, contains provisions that directly address many of the report’s recommendations.

She said a renewed partnership between her department and the Nunatsiavut government is already showing results, with a full complement of social workers now on staff in Inuit communities.

And Dempster said training for new foster parents has taken place in every Inuit community in recent months.

“Our goal is to support families so they can ensure the safety and well-being of their children, so they can grow up in their communities, closer to their families and culture, and achieve their full potential,” she said.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Nunavut lags behind rest of Canada for child care use, stats show, CBC News

Finland: Finland’s indigenous Sámi score victory in fishing dispute, Yle News

Sweden: Inequality a problem in Swedish schools: UNICEF report, Radio Sweden

United States: U.S. Attorney General hears from Indigenous leaders about justice problems in rural Alaska, Alaska Public Media