Taxing carbon in Canada’s diesel-dependent North

People living off-grid in the Northwest Territories witness climate change every day, but in remote communities where power and heat comes primarily from diesel generators, there are no easy alternatives to help stop the impact of a warming climate.

“If you’re living in Ulukhaktok, let’s say 350 people, way out in the Arctic… if you don’t have diesel fuel or heating fuel you’ve got no alternative,” explained outgoing Premier Bob McLeod.

According to McLeod, companies in the south of Canada often call asking why the government doesn’t bring them in to build solar or wind farms and install batteries at a cost of millions of dollars.

“You know, when the sun disappears in December and doesn’t appear again until the end of February, solar it’s not much use to you… and not every community has wind,” said McLeod.

“At the end of the day, when it’s 45-below for three months, you’ve got to have heat or else you’re going to freeze.”

Geography keeps costs and carbon intensity high

Twelve of the 33 communities in the Northwest Territories are only accessible by airplane, with another third of those communities connected by smaller roads which aren’t always paved.

“Most people don’t have any idea of how far people are separated. We’re 44,000 people spread out over 1.5-million square kilometres,” said McLeod.

Any surplus power generated off the Snare and Taltson hydroelectric dams further south can’t be shared beyond their limited grids, which means many of the small communities in the N.W.T. cannot take advantage of economies of scale.

Delivering fuel to the remote communities adds another level of carbon intensity to the mix.

If the summer barge misses its window to deliver the winter fuel supply, the only alternative is to fly-in millions of gallons of diesel over multiple flights – just to keep the lights on.

Carbon intensity versus carbon footprint

When it comes to total greenhouse gas emissions in Canada, the three territories emit a tiny fraction — one third of one per cent — of Canada’s overall greenhouse gas emissions.

That’s why outgoing Premier Bob McLeod believes he speaks for everyone living in the North when he expressed that there’s only so much they can do to reduce Canada’s carbon footprint.

“I mean, we’re doing our part,” said McLeod.

“You know you could shut everything down [in] the Northwest Territories, which I think a lot of people in southern Canada would want us to do,” McLeod said.

“I’m saying no matter what we do — it’s not — we’re not the problem… in my mind southern Canadians and the rest of the international world are the problems,” added the outgoing premier.

Canada falls within the top 10 global emitters when it comes to total greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), according to Environment and Climate Change Canada’s 2019 global greenhouse gas emissions report.

Everyone in the North is affected

Ask any northerner if they’ve witnessed climate change firsthand: the answer is absolute.

“I was helping to run a panel on climate change in Yellowknife one year after some fieldwork,” said Jennifer Baltzer, Canada Research Chair in forests and global change at Wilfrid Laurier University.

Baltzer has been running a research program in the Northwest Territories since 2011.

“We asked the audience, ‘Who has experienced climate warming firsthand in their lives?’ and everyone in the audience put up their hand … there was no one in the room that didn’t feel as though their lives had been directly impacted by climate warming,” said Baltzer.

Witnessing the change in small communities

Residents of Fort Providence said they can see a difference in the furs and skins of the animals they hunt and trap, and they blame climate change.

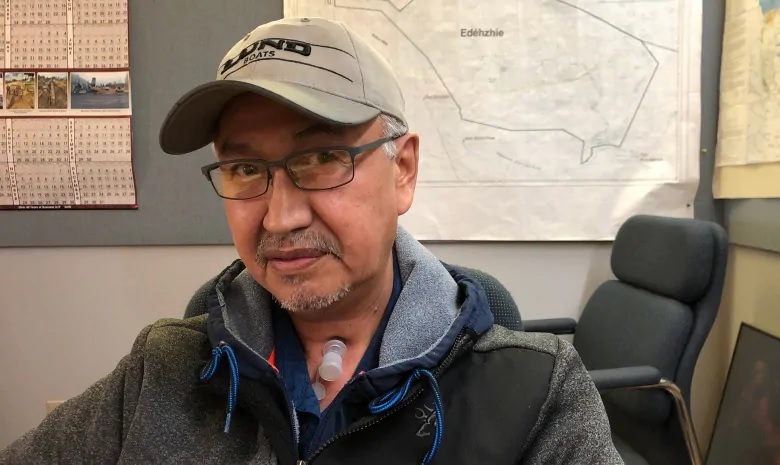

“A lot of our people now are finding it difficult to sell their fur because it’s not prime,” said Deh Gah Got’ie First Nation councillor Sam Gargan, who explained that a prime pelt has to be white and thick.

“You know, a lot warmer winters create a confusion among fur-bearing animals. You start growing the fur and turning their skin colour,” said Gargan.

Auctions won’t accept the pelts brought home by people in Fort Providence, according to Gargan, because the fur isn’t as thick as it once was and the colour is not the pure white that buyers expect — even at the height of trapping season.

The carbon tax in the North

The Northwest Territories government launched its version of the federally-mandated carbon tax on Sept. 1, 2019.

The tax is meant to encourage businesses and residents to use fewer fossil fuels and lower overall emissions. In the N.W.T., virtually all revenue the government generates from the tax goes straight back to taxpayers in the form of rebates.

But for many, concerns about fuel and energy bills are front and centre.

“Always this diesel price is going up,” said Xavier Canadien, chief of the Deh Gah Got’ie First Nation in Fort Providence.

According to Canadien, the hamlet of 700 people spends millions of dollars on diesel every year.

To reduce their costs, they’ve installed solar panels on their recreation centre and a biomass heater in their school. But Canadien said they just don’t have the capital to install and maintain more green energy projects.

“We don’t have a big pot of gold somewhere we can dig into for that kind of stuff,” he said.

Written by Tracy Fuller.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Community in northern Quebec to make the jump from diesel to hydroelectricity, CBC News

Finland: How will Finland become carbon neutral by 2035?, Yle News

Monaco: Sea level rise to provoke ‘profound governance challenges’ & ‘difficult social choices’ says UN climate report, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Emissions dropping in EU, but not in Norway, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Climate change threatens security and industry, Russian PM says, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Local councils in Sweden more interested in climate change preparedness, Radio Sweden

United Kingdom: Documentary will show climate change through eyes of pioneering scientist, Cryopolitics Blog

United States: Alaska remote diesel generators win exemption from pollution rule, Alaska Public Media