Historical, 150-year-old map of southwest Yukon on display in Northern Canada

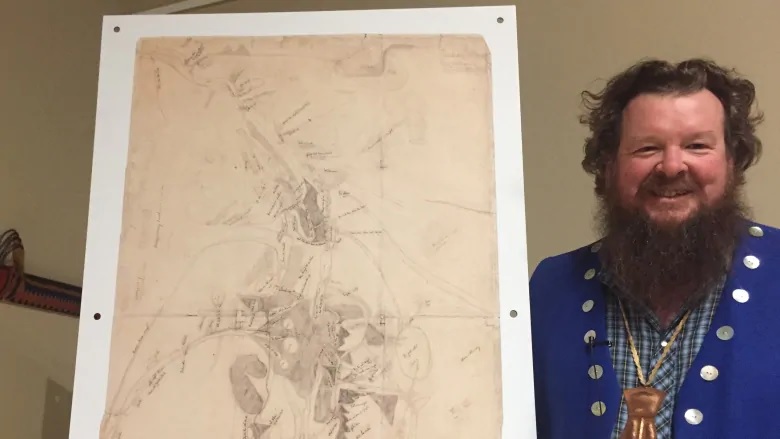

When a precious map arrived in the Yukon from San Francisco last week, Tom Buzzell was shocked at its size.

“It was actually smaller than I’d even pictured,” said the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations citizen.

“But yeah, it was emotional.”

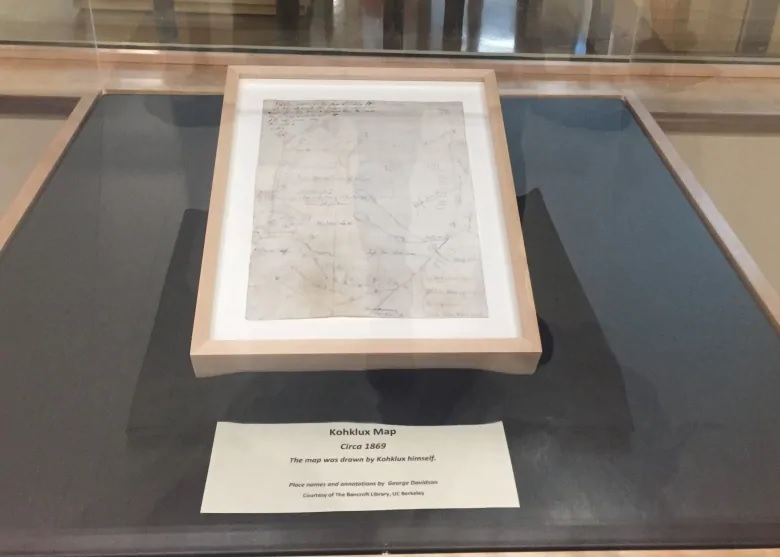

The map, just 12″ by 12″, may be small in size, but is large in significance.

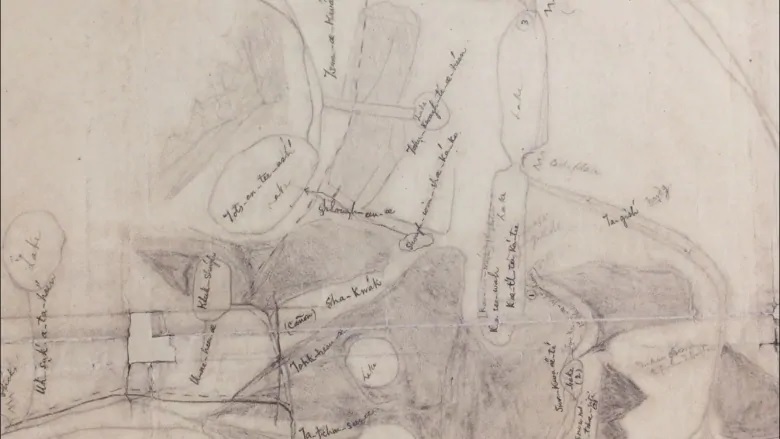

Made by Chilkat Tlingit Chief Kohklux in 1869, researchers say it’s the oldest known map of southwest Yukon.

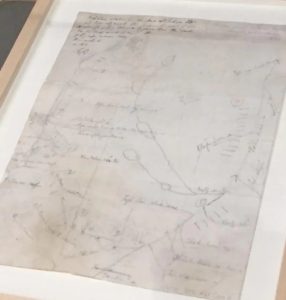

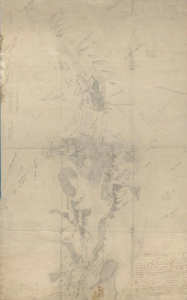

Drawn in pencil, it shows trade routes and landmarks stretching hundreds of kilometres inland from the village of Klukwan, Alaska, traversing the traditional territory of several First Nations.

“The map tells the story of the trip from Klukwan to Fort Selkirk, [Yukon]” said Buzzell.

“The way it’s drawn, it goes from right to left in a circle from start to finish. It’s not linear like we’d see a map today.”

Buzzell has been on some of the trails drawn on the map, including the route he uses to get to his trapline in the winter.

“I just find it very exciting that it shows a lot of the trails that we still use today.”

Buzzell was part of a committee that brought the map to the Yukon to celebrate its 150th birthday. A potlatch was held in Haines Junction last weekend to share stories and research about the routes and places shown on the map.

Yukoner tracked down map in 1983

According to records left behind by George Davidson, a U.S. surveyor, Chief Kohklux gave him the small map, as well as a larger, more detailed map, in 1869.

Davidson had travelled to Klukwan for a total solar eclipse and apparently impressed Kohklux with his ability to predict the darkness that swept over the Chilkat Valley during the day. In exchange for the two maps, he gave Kohklux information he documented about the eclipse.

Davidson returned to San Francisco with the maps, which he used to publish his own map of the region in 1901. It was Davidson’s map, donated to the Bancroft Library at the University of California Berkeley after his death, which alerted Yukon researcher Linda Johnson to the existence of Kohklux’s maps. They were referenced in Davidson’s map, but they weren’t part of the donation to the library.

Through some serendipity, the Kohklux maps were found in an old trunk by a bookseller and transferred to the Bancroft Library in 1982. That’s where, after nearly 10 years of searching, Johnson tracked them down in 1983.

With her help, the maps have been brought to the Yukon a couple of times — mostly recently in 1994, for their 125th birthday.

Journey north

Theresa Salazar, curator of the Western Americana collection at the Bancroft Library, travelled from San Francisco with the smaller Kohklux map. She said it was too difficult to bring Kohklux’s larger, more detailed map. Although it has previously visited the Yukon, Salazar said current air cargo restrictions made it impractical to bring this time.

“The crate would have had to been a big, large crate,” she said. “It just became so cumbersome that we could not manage it.”

Salazar says, in addition to having more details including more than 120 Tlingit place names, the larger map is special because of the collaboration that went into it. Kohklux’s two wives were contributors.

“I guess his wives spoke Chinook, which was … a communication trading language,” Salazar said.

“So you have a combination of all sorts of interesting linguistic things going on on that map.”

The English versions of the wives’ names were documented by Davidson and now researchers are working with the Tlingit to try to determine their Indigenous names.

Ancient footsteps

Although many Tlingit people had never seen the original copies of Kohklux’s maps, some have studied copies of them.

Tim Ackerman, who travelled to the weekend celebration in Haines Junction from Haines, Alaska, has organized expeditions on some of Kohklux’s trade routes, including up the Chilkat and Tahini rivers.

“It was always … [a] thing that I wanted to do, was go walk in his foot prints.”

Ackerman said he found archeological evidence of a camp that Kohklux likely used, including rolled up birch bark for starting a fire, and a rock shelter.

“It was really interesting to maybe even touch that piece of rolled up birch bark that he might have even stashed in that rock shelter.”

Ackerman said he records all the sites they find, so Kohklux’s history can be preserved.

Steve Smith, Chief of Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, said stories about the map have been passed down through the generations.

He said having the original map on site is a reminder of how important trading and relationships were between coastal and inland First Nations.

“They had very, very deep rooted and very important marital, familial, and economic relationships between Southern Tutchone Dän [people] and the Tlingit Ḵwáan.”

The small Kohklux map, as well another map, known as the Kandik map, will be on display at the Kwanlin Dun Cultural Centre in Whitehorse for a public event on Thursday evening. The Kandik map shows the Yukon River watershed and was drawn in 1880 by Paul Kandik, who researchers believe guided early traders.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: HMS Terror’s ‘incredible’ condition may offer new clues to Franklin Expedition mystery, CBC News

Finland: Finnish Heritage Agency scouring countryside for ancient monuments, Yle News

Norway: Roald Amundsen’s Maud back home 100 years after setting sail from Norway, CBC News

Russia: First icebreaker to reach the North Pole ends her days in a scrapyard, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Sweden, Norway team up to preserve ancient rock carvings, Radio Sweden