Where are the wolves? Satellite collaring planned for wolves on caribou winter range in northwestern Canada

Biologists in the N.W.T. are asking: where are the wolves?

That’s the question a proposed wolf collaring project aims to answer, as well as how wolves move between three threatened caribou herds on the central Barren Grounds.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty about the numbers of wolves on the central Barrens,” and how they move on caribou winter range, said Robert Mulders, the territorial carnivore biologist who applied for the research permit.

The project is the first in the N.W.T. to simultaneously track wolves that follow three different herds on the central Barrens, using collars. They include the Bathurst, Bluenose East and Beverly/Ahiak herds. If permitting is approved, collaring could begin in mid-February.

“We’re seeing very significant declines in these caribou herds … there’s a fairly intense pressure to sort of try to facilitate caribou recovery,” he said.

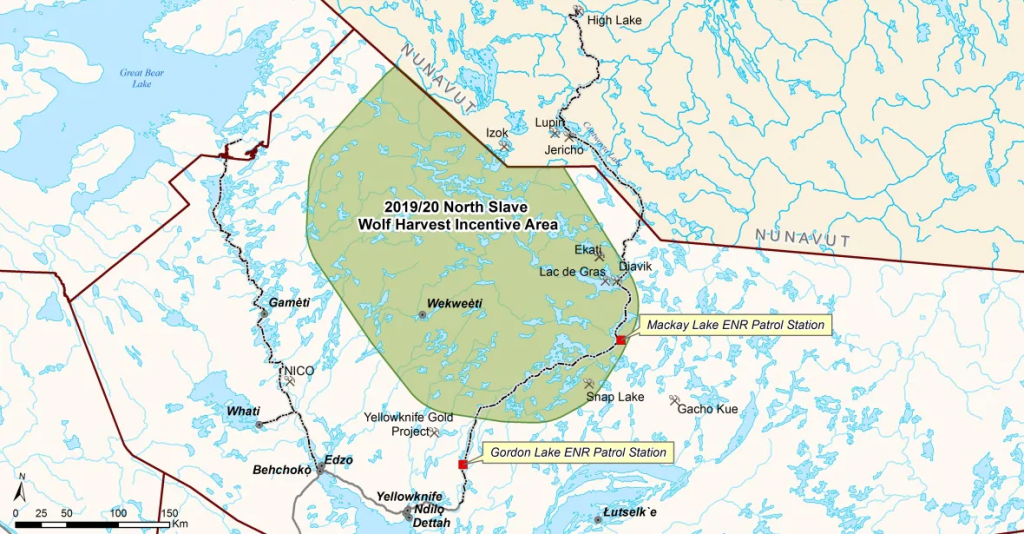

The territorial government began offering enhanced harvesting incentives for hunters to cull wolves last winter to help reduce the predator population and give caribou herds a chance at recovery.

The program drew criticism in the past from biologists who questioned its efficacy.

“We’re hoping that by applying pressure on wolves that we should see signs of recovery…. So these collars will be a very useful tool as we move forward,” he said.

The five year collaring project aims to collar 30 wolves: ten associated with each of the three herds.

A helicopter capture crew will track down the wolves from the air using locations from collared caribou. Researchers will use a net gun to trap wolves, entangling them with the net, Mulders said.

Each wolf’s neck is then secured with a yoke-shaped brace so the collar can be slipped on. The whole thing takes about 15 minutes, said Mulders. The wolf is released without being tranquilized.

The Iridium-GPS wildlife collars, which weigh about 880 grams each, collect location data up to five times a day. The data is sent by satellite back to the biologists.

Along with learning more about how wolves mix and move with caribou herds, the data could help researchers identify new dens and if wolves return year after year.

The data is also valuable to researchers and communities outside the N.W.T. says Earl Evans who chairs the Beverly and Qamanirjuaq Caribou Management Board. The Beverly herd is also listed as threatened.

“It’s a vast land and it’s huge. Wolves get swallowed up in it,” he said speaking about the lack of “concrete” information about their movement and populations.

“I understand wolves now are moving more into the calving grounds in the spring and killing more calves. Some of them are denning up there in the calving grounds where in the past they didn’t do that,” said Evans.

“These collars are going to be the only concrete information we are going to be able to get about wolves and their movements,” he said, which is good for biologists, communities and people trying to manage the herds.

The collaring program will run for five years, with some of the collars being replaced if they get damaged or because of wolf mortality.

A five-year proposal for managing wolves wintering in the Bathurst and Bluenose-East caribou herds will be unveiled Friday by the territorial and Tlicho Government.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Canadian Indigenous leaders stress need for less “colonial” approach to caribou conservation in North, CBC News

Finland: Finland’s wolf population up 10 percent, Yle News

Russia: Authorities in northwest Russia move to protect wild reindeer, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Swedish study seeks to understand what wild wolves eat, Radio Sweden

United States: Bill to protect ANWR passes early hurdle in Washington, CBC News