Glacier mass decreasing across Arctic but at different rates, says study

Glacier mass is decreasing worldwide with an average total loss of 267 billion tonnes of mass per year, says a new study.

The period looked at was between 2000 and 2019. The loss of glacier mass during this period also accounted for 21 per cent of the observed sea-level rise, the authors said.

The study, “Accelerated global glacier mass loss in the early twenty-first century” was published in the journal Nature on Wednesday.

Glacier mass loss has been accelerating by about 50 billion tonnes annually each decade since 2000, the study found.

Differentiation across Arctic

When it came to the circumpolar North in the period studied, it was one of the areas where regional variability was picked up.

About 50 per cent of worldwide glacier mass loss was in North America, the authors said.

Glaciers in Alaska, and those found along Canada’s border with Alaska, accounted for 25 per cent.

Glaciers in Canada’s eastern Arctic accounted for 21 per cent of the loss. Glaciers in B.C., Alberta and the Lower 48 in the U.S. accounted for a further three per cent.

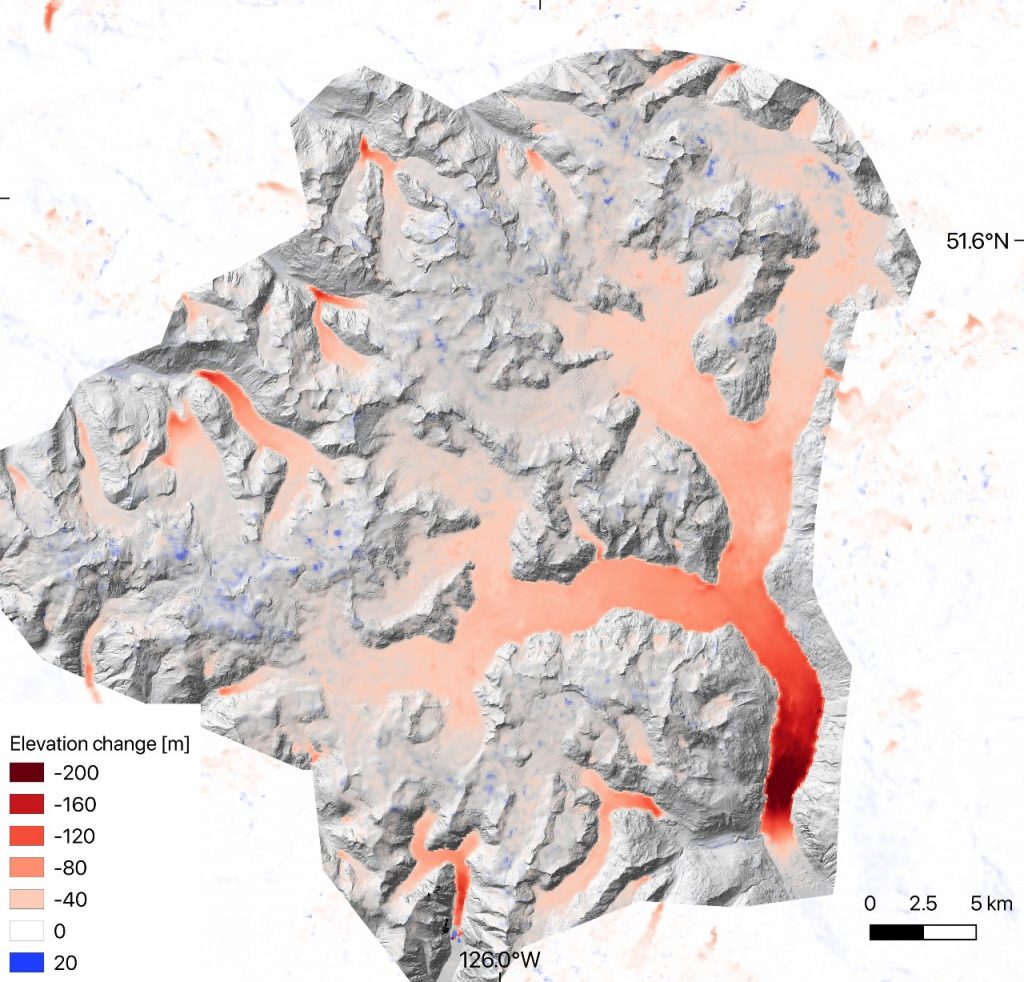

An animated graphic showing the thinning of Iceland’s glaciers between 2000 and 2019

(Hugonnet et al. (2021), Nature)

Meanwhile, in some other areas of the North, glacier thinning was slowing down.

“One interesting things that we see in the last 20 years is the trend may be set by an increase in temperature, but we do pick up regional variability and how glaciers are responding to shorter-term climate and weather phenomena over the course of a given decade,” said Brian Menounos, a co-author of the study from the University of Northern British Columbia, in a phone interview.

“In the Arctic region in general, we see that in the last ten years there’s this pattern that we refer to as the North Atlantic anomaly, that is with glaciers on the eastern fringe of Greenland, Iceland and Scandinavia we see the rates of mass loss or thinning have actually slowed down.”

Glaciers in Arctic Russia also aren’t losing mass at the same rate as in northern North America.

“We know those glaciers [in Arctic Russia] are situated at fairly high latitudes,” Menounos said. “When you look at the magnitude of the melt from those glaciers it’s not as strong as their counterparts to the west. But that’s not to say that the magnitude of the melt from Arctic Russia won’t increase. We know it will under future climate change and once you get to that point, you’re getting a substantial amount of ice in that part of the world starting to contribute as well.”

Supercomputer images

To do the study, the researchers used satellite and aerial imagery to look at 217,175 glaciers around the world to estimate the mass loss.

A supercomputer, co-funded by the University of Northern British Columbia and the Hakai Institute, a Canadian scientific research institution, also located in British Columbia, created digital elevation models from over 440,000 images.

“The UNBC and Hakai Institute computer facilities allowed us to generate time series of surface elevation, essentially time-varying topographies, at 100-metre resolution for about one-half of a billion individual locations over Earth’s glaciers and their surroundings,” Romain Hugonnet said in a news release. Hugonnet is the study’s lead author and is with the University of Toulouse in France and ETH Zurich, a Swiss university.

Creating the elevation models required the equivalent of 584 modern computers running for a year.

International cooperation is key

Menounos says continued international collaboration is key to better understanding the environmental changes in the coldest parts of the planet.

“We collect all these observations, not only as a report card for how the cryosphere is doing, but also because it provides important baseline data to improve models going forward,” he said.

“We need to have good predictive models that forecast how these glaciers are going to change in the decades ahead and how that’s going to affect things like regional water availability and sea level rise. And the way you improve and develop models is testing and evaluating them against good observational data.

“International collaboration and working together is key going forward. There should be no boundaries when working on science.”

Write to Eilís Quinn at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Warming Arctic shrinking Canadian glaciers at alarming rate says study, Eye on the Arctic

Iceland: Iceland glacier lost to climate change to get memorial ceremony this month, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Climate change hits back at Svalbard, coal mine flooded by melting glacier in Norway, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Retreating ice reveals new land in Arctic Russia, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Glacier in central Sweden “collapsing” as climate warms, Radio Sweden

United States: Melting glaciers are triggering the world’s biggest tsunamis, CBC News