Food insecurity a public health crisis that needs action, says Canadian Inuit org

The national Inuit organization in Canada released their Inuit Nunangat Food Security Strategy on Monday, saying the prevalence of food insecurity in the Inuit regions of the country remain “unacceptably high.”

“Our vision is to end hunger and support Inuit food sovereignty throughout Inuit Nunangat by helping to develop a sustainable food system that reflects our societal values, supports our well-being, and ensures our access to affordable, nutritious, safe, and culturally preferred foods,” Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) said in their strategy.

(Inuit Nunangat is a term used to refer to Canada’s four Inuit regions: the Inuvialuit Settlement Region in Canada’s Northwest Territories; Canada’s eastern Arctic territory of Nunavut; Nunavik in northern Quebec; and Nunatsiavut, in the Atlantic Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador.)

“The high prevalence of food insecurity among Inuit is among the longest lasting public health crises faced by a Canadian population. Moreover, Inuit face the highest documented prevalence of food insecurity of any Indigenous people living in a developed country.”

Climate change, living costs among food insecurity drivers

– Rome Declaration on World Food Security, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

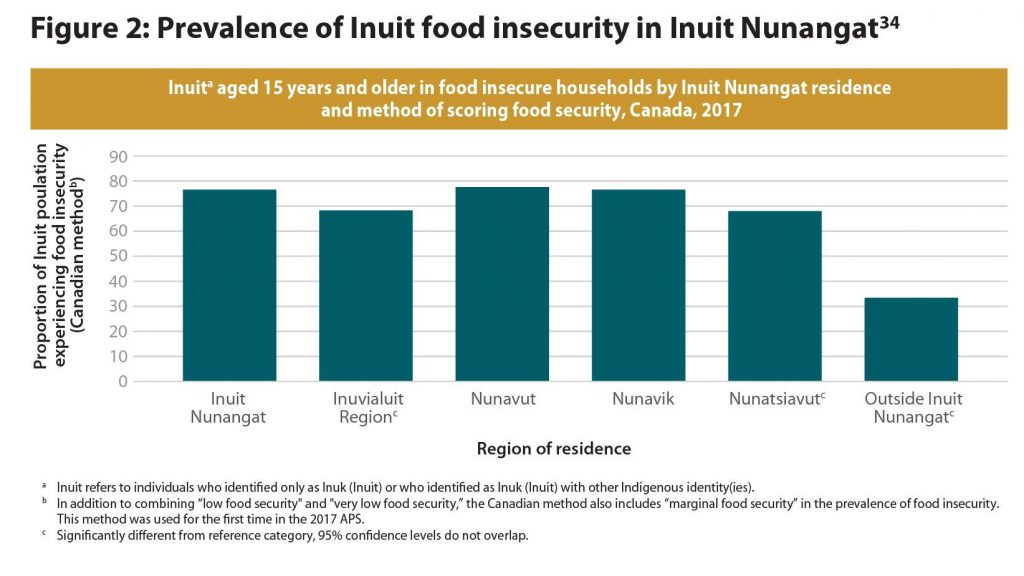

The ITK strategy says information and research on food insecurity in the Inuit regions of Canada is limited, but that the Statistics Canada 2017 Aboriginal Peoples Survey provides the most recent set of uniform data.

That survey put food insecurity among Inuit over 15 years old at 76 per cent.

“For Nunavut Inuit, harvesting, processing and consumption of country foods is deeply linked to community ethics and Inuit identity,” Aluki Kotierk, president of Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, the Nunavut land claims organization, said in a statement.

“The maintenance and building up of our kinship relationships and with other community members is a necessary and integral part of Inuit culture. We must make a shift from thinking about food security to food sovereignty. Food sovereignty captures the policy approaches required to address the underlying issues impacting Inuit and our ability to respond to our own needs for healthy, culturally appropriate, and customary food. It means empowering Inuit to feed our own communities.”

More data needed on youth

For those under 15 years old, the food insecurity data is less clear.

“No current Inuit Nunangat–wide data exists about the prevalence and impacts of food insecurity among Inuit children below 15 years old,” the strategy says.

The 2007-2008 Inuit Health Survey suggested children are particularly vulnerable to food insecurity, but an upcoming Inuit Health Survey will seek to address some of the current knowledge gaps.

Infrastructure challenges a key driver of food insecurity

The strategy outlines four main drivers behind food insecurity in the Inuit regions of Canada: poverty, the high living costs associated with living in the North, climate change and contaminants, and the legacy of colonialism on the food system in the North.

Several remedies are outlined in the strategy: increased Inuit self-determination in everything from food security to poverty reduction, to policy initiatives; greater support for harvesters and Inuit food sharing networks and increased research. A reduction of the infrastructure deficit in the North and investments in things like ports and air travel will also be a key factor in alleviating food insecurity, ITK says.

The 2017 Statistics Canada report, The Insights on Canadian Society: Food insecurity Among Inuit Living in Inuit Nunangat, put together from data in the 2012 Aboriginal Peoples Survey, found that it costs between $328 to $488 per week for a four-person family in an isolated Inuit community to provide a healthy diet, while in southern Canada, it would cost $209 for a family of four.

The ITK strategy points to the kinds of investments happening in places like Greenland and Alaska, that have gone a long ways towards helping reduce food costs. Examples include the U.S. Department of Transportation’ Essential Air Service program that ensures a minimal level of service to small communities and which subsidizes air carriers serving approximately 60 rural Alaskan communities.

The report also points to the amount of paved air strips in those jurisdictions, compared to Canada. Fourteen of the 18 air strips in Greenland are paved, as are 61 in Alaska, “…more than six times the number found in Canada’s three territories combined,” the strategy says.

“Canada’s unwillingness to seriously invest in the region’s marine and aviation infrastructure sets it apart from other nations with Arctic territory, and its neglect of the region’s infrastructure needs contributes to high food prices and high cost of living throughout the region.”

Further study needed of Nunavik cost-of-living subsides

In Canada, the examination of cost-of-living subsidies in Nunavik is also recommended, as well as the successes of the Nunavik co-op system.

La Fédération des Coopératives du Nouveau Québec is owned by its approximately 12,000 members in Nunavik’s 14 communities and their model of subsidizing freight cost differences when transporting food and other goods to the region, while still remaining profitable, needs further study, the strategy says.

In addition, the 2019 six cost of living measures (elders assistance, airfare reduction program, country food community support program, household appliance and harvesting equipment program, food and other essentials program and the gasoline program), supported by $115.8 million over six years by the Quebec government, has also gone along way to reducing costs in the northern Quebec.

“The food and other essentials program provides rebates between 15 and 35 per cent on the majority of items purchased in Nunavik stores to all Nunavimmiut (people from Nunavik) with the aim of aligning prices with those in southern Quebec stores,” ITK says.

“The rebate can be applied to food items and goods that are already subsidized by Nutrition North Canada, further reducing prices. Together, this suite of programs represents the only comprehensive policy initiative intended to help bring an Inuit region in line with the rest of Canada by reducing the high cost of living.”

Despite the promising measures, the cost of living in Nunavik still remains higher than places like Quebec City, but are worth further examination, ITK says.

“The federal government should build on promising measures developed by Nunavik Inuit and Quebec and take the lead in advancing comprehensive cost-of-living reduction measures throughout the region,” the strategy says.

Monica Ell-Kanayuk, president, Inuit Circumpolar Council Canada, the Canadian chapter of the international Inuit organization that represents Inuit in Russia, Canada, Alaska and Greenland, says the strategy is an important building block to improve health in the North.

“From a circumpolar perspective we are pleased to see this strategy launched,” Ell-Kanayuk said in a news release.

“Many issues are addressed in the strategy. For example, food insecurity is a serious public health issue because it is so tightly linked to an individual’s overall health and well-being. Inuit are often forced to compromise on the nutritional quality or quantity of the food we consume, creating risk for poor health outcomes. This strategy will help overcome this problem.”

Write to Eilís Quinn at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Climate change driving food insecurity in First Nations communities while Canada stands by, report says, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Finland’s farming sector in crisis: report, Yle News

Norway: Alarm bells ringing for Atlantic salmon in northern Norway, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: 2018 drought took toll on Swedish farmers’ mental and fiscal health, research says, Radio Sweden

United States: This Alaskan spice shop brings new flavors to Indigenous dishes, Alaska Public Media