German project to house everything published in Siberian and Arctic languages to seek new funding

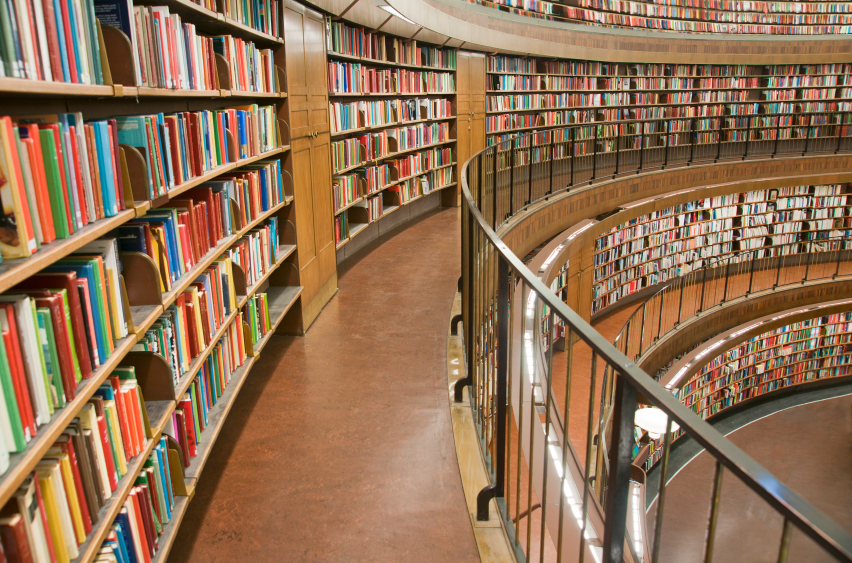

A project at Germany’s Goettingen State and University Library that seeks to house everything printed in Siberian and Arctic languages will seek new funding this year to continue the program.

“We buy literature in about 70 languages spoken in Siberia and the Arctic, starting from Scandinavia with the Sami going over to the Samoyeds and other Siberian peoples and nations, and then Greenland, Canada and Alaska,” said Johannes Reckel, head of the department for Central Asian, Siberian and Circumpolar Languages at the institution, where he’s been responsible for the project since 2004.

“Or course it’s always been difficult to buy this literature, but basically we’re interested in buying anything in these languages.”

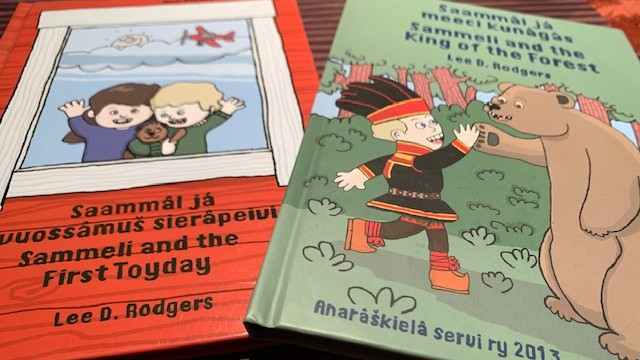

The collection has works ranging from novels to school books to reports.

Canadian titles in the collection include everything from children’s books by Inhabit Media, an Inuit-owned publisher in the eastern Arctic territory of Nunavut, to text books from Nunavut Arctic College and the Nunavut Deptartment of Education, to reports by Inuit organizations like Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada and Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, the Inuit land claims organization.

The importance of printed works

While digital material is also collected, the focus on printed material is to ensure works don’t get lost.

“Digital material can come and go, but printed material can be protected,” Reckel said in a phone interview. “We want this material to be available even in a hundred years time.”

The collection is built by reaching out to publishers that handle books in the target languages as well as places like educational departments, in order to acquire school books.

Material from Greenland and Canada is relatively rich, but buying works from Alaska, Arctic Russia and Siberia, presents more of challenge, he said.

“Publications from Alaska are rare, there just doesn’t seem to be much published in their Indigenous languages, but in Siberia, it’s nearly zero because so many of the minority languages are nearly dead.”

Reckel says he scours the Russian National Bibliography weekly and orders anytime he finds a book in one of the target languages, but that even then, there’s only a fifty-fifty chance they’ll get the book.

“It’s difficult in general to get literature from Siberia,” he says. “Even if a book is published in a Siberian language, sometimes the print numbers are so low, there just isn’t anything available. We order a lot, but we never get more than a maximum of 50 per cent.”

But Reckel says they never get discouraged and believe in the importance of making sure such titles don’t get lost.

International attention on the Uyghur population is just one example of why it’s so important for libraries to build up collections steadily and slowly over time.

“There is high demand for Uyghur material now because they are in focus after reporting on their treatment in China,” Reckel said. “But before that, no one was studying Uyghur language or culture or society so there was very low demand.

“That’s why we cannot wait for high demand to start collecting a literature. We cannot start collecting in 50 years, literature that was published now. What’s important is that when demand and interest is there, these works are already on the shelves.”

Long history

Germany does not have a centralized library system, and no national library like Library and Archives Canada.

In 1949, the German Research Foundation established a system assigning large libraries certain areas for collections.

Gottingen was assigned the collections of Paleo-Asiatic and Altaic books, which includes Eskimo–Aleut languages.

But the special collections system was stopped in 2015 and was replaced by a new system with less reliable funding that has to be reapplied for on a regular basis.

The Goettingen program applied for funding under the new system three times before finally getting approved for three years in 2019.

The funding runs out this year, and Reckel says they’ll reapply and that the project is too important to stop.

“One of our aims is buying printed books and the other aim is collecting and distributing information on our website. We want to enable the widest possible contact within the field and raise awareness about the kind of language literature we have available online.”

Write to Eilís Quinn at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Mark Indigenous languages decade by making Inuktitut official in Canada: Inuit UN rep, The Canadian Press

Finland: Everyone encouraged to boost Sami language visibility in Finland, Norway and Sweden this week, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Indigenous and minority language names for Norway now have official status, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Can cross-border cooperation help decolonize Sami-language education, Eye on the Arctic

United States: Inuit leaders applaud UN move to designate International Decade of Indigenous Languages, Eye on the Arctic