Is Canada’s Northwest Territories in a mental health crisis? MLA, health minister at odds over the answer

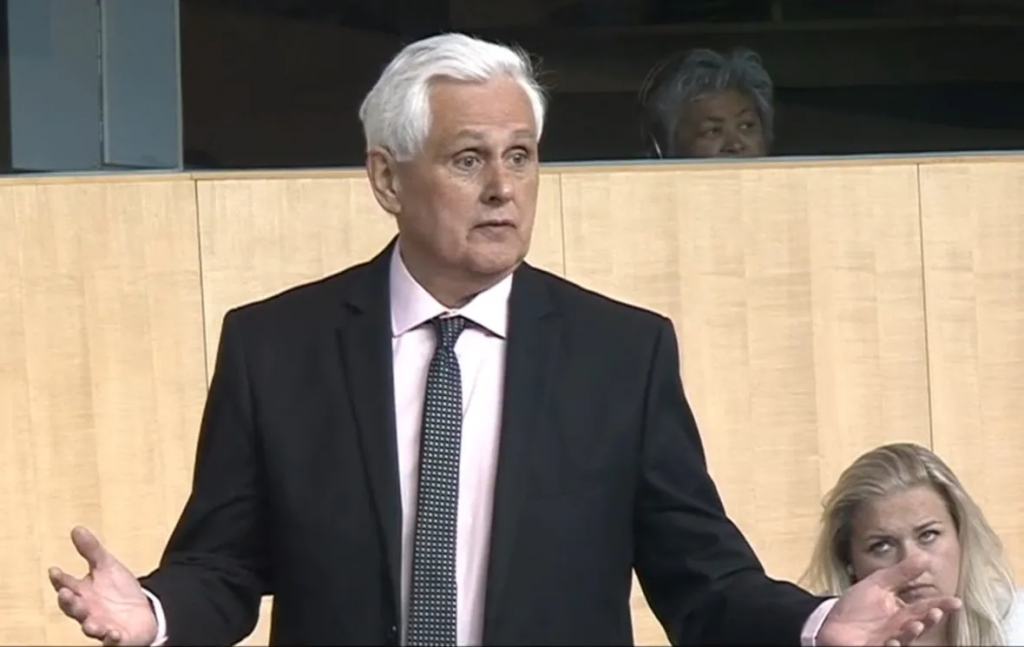

Great Slave MLA says territory is at a critical point; Health Minister says it’s nothing N.W.T. can’t handle

Warning: This story includes discussion of suicide.

Is the Northwest Territories in the midst of a mental health crisis? The minister of Health and Social Services doesn’t think so.

Minister Julie Green denied the assertion Wednesday, despite members of the Legislative Assembly pointing to the North’s high suicide rates; reports of increasing family violence, drug overdoses and stressed out workers; and recent reports of children as young as 10 and 12 attempting to take their own lives.

The pandemic, suggested members for Great Slave, Hay River South and Kam Lake, twisted the knife in what was already a festering wound.

Members for Monfwi and Nunakput reminded the house that the Tłı̨chǫ and Beaufort Delta regions were wrestling with suicide, addictions and mental health problems long before the pandemic, and there has been no clear indication of improvement.

Great Slave MLA Katrina Nokleby spoke of children “as young as 10 and 12 years old” having recently attempted suicide, as well as a third young adult who died by suicide.

“Will the minister finally admit that we are in a mental health crisis here in the Northwest Territories, after two years of this pandemic?” she asked during question period.

The minister would not.

“I recognize that the pandemic has been incredibly stressful for almost everyone. It produced a lot of anxiety, depression, loneliness, especially for for people who live on their own, like elders,” said Green.

Still, she said, the territory has been able to keep up with demand for mental health services throughout COVID-19.

“So I feel confident that we’re not facing anything that we can’t deal with,” said Green.

‘What is HSS doing to save our children?’

But what would constitute a mental health crisis?

How many people struggling with addictions; how many extended absences from work, classes missed, nights in hospital or cells, suicides and suicide attempts; what barriers to timely and appropriate care, would qualify?

There is no set threshold for a “crisis.”

The Centre for Addictions and Mental Health in Toronto, the largest mental health teaching hospital in Canada, says the whole country is experiencing a mental health crisis.

The hospital reports that just half of Canadians experiencing a “major depressive episode” get “potentially adequate care.”

It says Indigenous young people are five to six times more likely to die by suicide than their non-Indigenous counterparts, and suicide rates among young Inuit are 11 times the national average — and the highest in the world.

In the N.W.T., “we have no residential trauma program, no residential treatment program for youth, no child and adolescent unit at Stanton [Territorial Hospital], and the solution seems to be to ship vulnerable people off to another part of the country, causing further traumatization,” said Nokleby.

“What is HSS (Health and Social Services) doing to save our children?”

Similar exchange, but nicer

Around this time last year, a similar back-and-forth between Nokleby and Green turned vitriolic when Green disagreed with Nokleby’s claim that the territory was in a mental health crisis.

Green charged Nockleby with “soliciting horror stories on Facebook,” and being “gratified with that.” Nokleby called Green’s comments “disgusting.”

Green later apologized and withdrew her remarks.

This time, the exchange was decorous, by comparison.

Green commended Nokleby for raising the issue, saying, “obviously, every parent’s worst nightmare is to fear that their child has suicidal thoughts or has attempted or completed a suicide.

“I appreciate her shining a light on that. I think it’s very important to do that.”

Green said a community counselling program is available to people and families, and there’s an app, called the Strongest Families Institute, that’s geared toward parents. She added families can attend counselling together, through the Child and Youth Care Counselling program.

“So there are services that are in place and available immediately to families in need,” said Green.

Biggest challenge is recruiting staff, says Green

Hay River South MLA Rocky Simpson, however, suggested mental health services aren’t so accessible.

“We actually place people on waiting lists to get mental health supports,” he said.

Simpson asked Green whether Health and Social Services is tracking mental health issues arising from the pandemic.

Green said the government has been tracking “social indicators” since the beginning of COVID-19, and publishing them online.

“The use of our programs has varied over time. It was lower at the start of the pandemic and greater now,” she said.

Green said there is no wait list for the community counselling program. People can make same-day appointments, and see someone in person, unlike earlier in the pandemic when most everything was done virtually.

She said right now, her department’s biggest challenge is recruiting staff. In some cases, a lack of housing is making vacancies harder to fill.

“But we continue to advertise for the staff and to fill the positions as quickly as possible, knowing how important they are,” said Green.

If you or someone you know is struggling, here’s where to get help:

- Canada Suicide Prevention Service: 1-833-456-4566 (phone) | 45645 (text).

- Kids Help Phone: 1-800-668-6868 (phone), live chat counselling on the website.

- Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention: Find a 24-hour crisis centre.

- NWT Help Line: 1-800-661-0844.

This guide from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health outlines how to talk about suicide with someone you’re worried about.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Mental health in Arctic Canada – Can community programs make the difference?, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Climate change worries Finland’s young reindeer herders, Yle News

United States: Lack of village police leads to hiring cops with criminal records in Alaska: Anchorage Daily News, Alaska Public Media