Lack of clean water in Nunavik means schools are closing, staff fleeing

Dozens of employees at primary and secondary schools in Nunavik are sounding the alarm about the region’s deteriorating water supply, saying the situation is putting their students at risk, a union report seen by Radio-Canada shows.

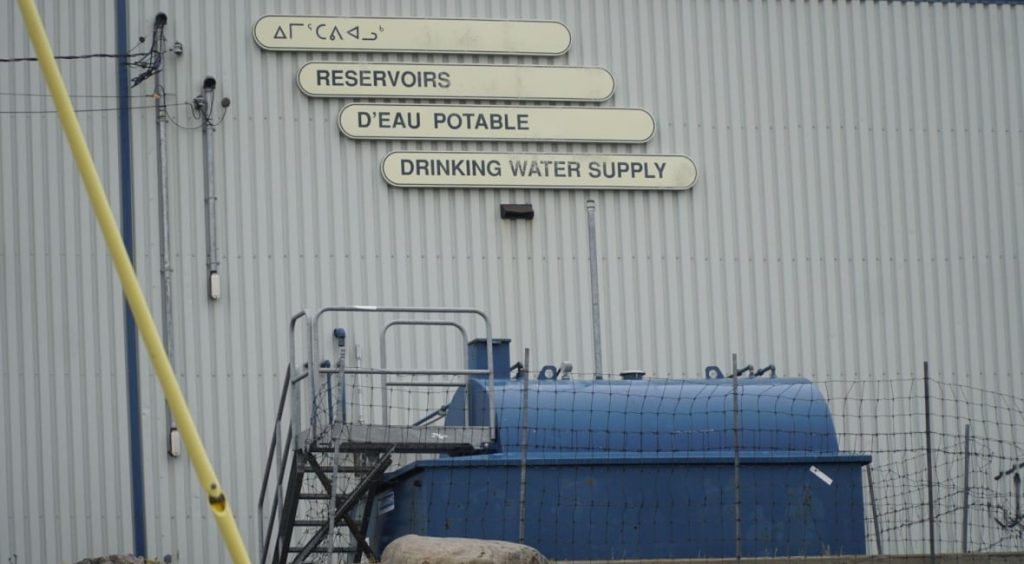

Thirteen of the 14 towns in Nunavik don’t have an aqueduct or sewer system. People there normally rely on tanker trucks to supply drinking water and remove wastewater.

But in recent months there have been supply interruptions because of broken infrastructure, a lack of trucks and a worker shortage, problems that were worsened by the pandemic and a harsh winter last year.

As a result, Nunavik residents have had to boil water and to do without running water to wash or flush their toilets.

Employees at the Kativik Ilisarnilirniq school board, most of them Inuit, denounced the poor quality of life in a report written by the Centrale des syndicats du Québec (CSQ), one of the largest trade unions in the province.

Radio-Canada was able to see the internal report — which collected testimony from 75 people — and is expected to be made public soon.

One employee said in the report that students are getting skin infections.

Another person voiced concerns about the fact that students aren’t able to wash their hands after going to the bathroom, saying it creates a perfect environment for bacteria to spread.

A third employee said she isn’t able to do laundry or wash her children’s bottles, and that her family once had severe diarrhea for multiple days because they drank contaminated water.

“Our people can’t go to the bathroom and flush, they have to use buckets to relieve themselves, they can’t wash their clothes, wash their dishes,” said Larry Imbeault, the president of the Association des employés du Nord québécois (AENQ-CSQ), one of the unions in Nunavik.

Schools forced to close

The water supply issues forced 15 school closures in Ivujivik, Kangirsuk, Inukjuak, Puvirnituq, Akulivik et Aupaluk during the last school year.

It’s likely there would have been even more closures had COVID-19 not shut down schools in the fall, the Kativik Ilisarnilirniq school board said.

The board denounced the ongoing situation and voiced its support for its employees.

“We need to stop taking this [situation] with a grain of salt,” said Jeannie Dupuis, the board’s deputy general manager. “It’s the basic needs of students that aren’t being met.”

And it’s getting harder and harder for the staff to deal with the situation as well, she said.

Thomassie Mangiok, the principal of Ivujivik’s primary and secondary school, Nuvviti, said the situation is frustrating.

“We have a water filtration system [at our school] so when students have a hard time getting good water at home, they come [here] to get it,” he said.

But when there are no tanker trunks available to empty the school’s wastewater reservoirs and the building is forced to close, it’s a problem, he said.

Ivujivik’s 350 residents are currently obliged to get their water from a nearby river and boil it. Ever since the local water filtration plant suffered damage last winter, the water supply has been repeatedly contaminated.

“We feel left out, as if we weren’t also Quebecers,” Mangiok said.

Scaring staff away

The dire living conditions caused by the water shortage are making it harder to attract and retain staff, according to Carolane Desmarais, the president of the Syndicat du personnel professionnel de l’éducation du Nunavik et de l’Ouest de Montréal (SPPENOM-CSQ), a union representing about 130 specialists such as psychologists and speech therapists.

“People who have been working in Nunavik for a long time are contacting us and telling us, ‘I don’t know if I will continue,'” Desmarais said.

The region, which has about 3,300 students, is also grappling with a severe shortage of teachers. Some 65 teaching positions are still vacant.

In comparison, the Centre de services scolaire de Montréal, one of the school boards in Montreal, is missing 24 teachers for 110,600 students.

“It’s becoming hard for us to advise other [teachers] to come and work here … and it’s becoming hard for us to stay here,” an employee said in the CSQ report.

The lack of teachers has forced the Nunavik school board to cancel some mandatory courses like french and math.

“If we don’t have teachers, we simply cannot offer the course,” said Dupuis.

Mangiok said he sees the consequences of this shortage on a daily basis. The region has had a school drop-out rate of about 80 per cent for the past four years.

“We never know if we’ll be able to provide services for our students,” he said. “Isn’t education important?” he said.

He said Nunavik students are Quebec citizens too and deserve to have the same opportunities as anyone else in the province.

The CSQ’s vice-president, Anne Dionne, echoed Mangiok’s comments, saying it is “frankly shocking” that students have to suffer from the closures.

“It makes no sense that such situations are trivialized, as if it’s normal because it’s in the north,” she said. “These situations would never be tolerated elsewhere in Quebec.”

“It’s time our elected officials take this issue seriously,” echoed Imbeault. “It’s fun to see them come to the north to take a picture — it looks good in the newspapers — but it’s time the issue gets resolved.”

Negotiations with the province

The office of outgoing Minister of Indigenous Affairs Ian Lafrenière told Radio-Canada that the province is following the situation closely and is providing some support, for example by sending additional tanker trucks.

“Minister Lafrenière visited Nunavik’s 14 villages [this spring] and was able to see firsthand the technical challenges some of these communities face,” said his communications director Mathieu Durocher.

Durocher said the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing gives funding to the Kativik Regional Government (KRG), which oversees the Inuit communities in Nunavik, as part of a program to buy equipment and build infrastructure for people living in the north.

It’s up to KRG to decide how that money is spent, in collaboration with the 14 villages, he said.

Lafrenière’s office said negotiations are also underway to renew $120 million in funding over six years to improve water infrastructure in the region.

The KRG declined to comment on the ongoing negotiations but told Radio-Canada that it would have more flexibility to allocate grants soon.

It said while it provides technical assistance to the region’s 14 villages, each town is autonomous and responsible for its own repairs and maintenance work.

Paul Parsons, Kativik’s general manager, said many solutions have been put in place. For example, new tanker trucks should be arriving by boat in the coming weeks.

When asked whether he thinks the region needs more funding, Parsons admitted that “everything” costs are a lot more in the north. “It’s clear we do a lot less with the same amount,” he said.

In reaction to Radio-Canada’s report, Quebec Liberal Party Leader Dominique Anglade said on Wednesday that there is “a lot of work to do” and that collaboration is essential to solve this issue. She is planning to visit the region on Sunday.

Maïtée Labrecque-Saganash, the Québec Solidaire candidate for Ungava (the riding that encompasses Nunavik), also reacted to the report.

“In Quebec, there is a humanitarian crisis that we don’t hear about,” she said on her Facebook page. She said the region needed a representative that would “really bring the voice of the north” to the National Assembly.

The Parti Québécois candidate for Ungava, Christine Moore, called the situation “deplorable” and criticized the Legault government for its “inaction” on the issue.

Based on a report by Radio-Canada

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Health care in Nunavik – What the candidates say …, Eye on the Arctic