‘He’s finally being recognized’: Indigenous veterans honoured this week in N.W.T.

Last Post Fund marks graves of veterans across Canada

A grey headstone stands out in the freshly fallen snow at Lakeview Cemetery in Yellowknife.

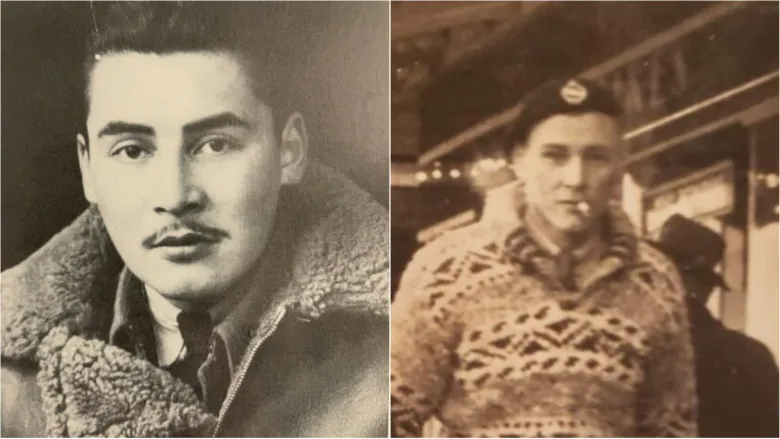

It belongs to Augustin Beaulieu, a Second World War veteran originally from Fort Resolution, N.W.T., who served with the Canadian Scottish regiment.

This is the first National Indigenous Veterans Day where his grave will be marked with a military headstone, courtesy of the Last Post Fund, a non-profit organization that works to ensure no veteran is denied a dignified burial.

Before the headstone, Beaulieu’s final resting place was marked with a wooden cross. It had rotted away over the years, leaving his gravesite unmarked and unknown.

Through research by Floyd Powder, Beaulieu’s grave was found and restored. Powder, a veteran himself, volunteers with the Last Post Fund identifying grave sites. He helps to locate unmarked veterans’ graves across the Northwest Territories, then works with families to arrange for a military headstone to commemorate their service.

“We’re so grateful that he’s finally being recognized,” said Adele Tatti, Beaulieu’s granddaughter. She said her family knew he was buried in Yellowknife but had no idea where.

Tatti lives in Hay River, N.W.T., and says the next time she visits Yellowknife, she plans to place a poppy by his headstone.

“He’s brought a lot of our family, who were a little bit disconnected for a long time, back together,” Tatti said.

The Last Post Fund was created in 1909 for all veterans, but it wasn’t until 2009 that it started focusing on Indigenous veterans. In 2019, it established the Indigenous Veterans Initiative to mark Indigenous graves and to add traditional names to existing graves.

Since April of 2020, Powder said the program has installed 30 headstones across the territory.

He said he has about a dozen others he’s hoping to have in place by next summer.

“At the end of the day, yes, it’s for the families’ benefit, but more importantly it’s for that deceased veteran,” Powder said.

That includes veterans like Métis pilot Robert “Bobby” Douglas, who served two tours in the Second World War. He, like many Indigenous people, had to give up his treaty status to serve in the war.

One week before he died in October 2020, he got it back, his son Sholto said.

Douglas is buried in Behchokǫ̀, N.W.T. His grave has also been marked with a military headstone, along with an infinity symbol — the symbol of the Métis.

“They may never know my father. But they’ll see that he served this country,” Sholto said during a visit to the cemetery last month.

Sholto said his father, like many Indigenous soldiers who served, felt an obligation to defend their homeland, despite the widespread racial discrimination and prejudice at the time, opinions that lingered after the war.

Many Indigenous veterans were never treated the same as other veterans who came back to Canada.

“Indigenous veterans, when they retired from their service and after World War One and Two, and even [the Korean War], they were denied benefits,” Powder said.

That’s why, in addition to his work researching and identifying graves, he maintains a list of veterans in the N.W.T. to keep them informed of current benefits for things like medical programs they may be eligible for.

Sholto applauds the work Powder is doing for Indigenous veterans.

“They were the forgotten soldiers of Canada. Forgotten veterans,” he said.

“Whether it’s a Métis or whether it’s a First Nation person, they did everything else that everybody else did. They’re no different.”

-with files from Juanita Taylor and Kate Kyle

Related stories from around the North:

United States: Veterans from Indigenous Alaskan village have war stories archived online, Alaska Public Media