Connecting through culture—How Isaruit became a haven for Ottawa Inuit

OTTAWA-Christine Awa, originally from Pond Inlet, Nunavut, discovered her love for Ottawa during a medical trip to the city with her then-infant son. She made the decision to raise her kids there, but admits the separation from her Inuit culture was a challenge.

Then in 2023 she discovered Isaruit Inuit Arts at Ottawa’s former Rideau High School building. There, she made ulus (traditional knives), then went on to do jewelry making and working with materials like antler.

“A lot of us [here in Ottawa] are limited to exercising our culture in our own homes,” Awa said. “But [Inuit culture] isn’t really just about that, it’s about being part of a whole community.

“Coming here, you feel all that love and positive energy. It’s very comforting, and very healing, and I’m extremely thankful for this place.”

‘This place is always here for you’

Isaruit, which means “wings” in Inuktitut, originated as a women’s sewing center in 2017 after five grandmothers from Inuit families recognized the need for a space in Ottawa where women could sew and share traditional patterns.

But by 2021, the organization had expanded into a drop-in center for men, women, elders, and youth. It now also offers hot meals, traditional food, mentorship in various Inuit arts and crafts, and provides free access to traditional materials.

Hayden Stuart, 28, originally from Tuktoyaktuk in the Northwest Territories, came to Ottawa for school in in 2014, but liked the city so much he decided to stay. Now Isaruit’s technical support worker and weekend Inuit Games coordinator, he says Isaruit plays an important role for Inuit in the city.

“I feel like this place is my family,” he said. “From the moment I stepped in here they accepted me with open arms and said, ‘Hey, come on in. You want a cup of coffee? You want to do art?’

“That’s the message, no matter who you are, what background you have, where you come from, this place is always here for you.”

Haven for carvers

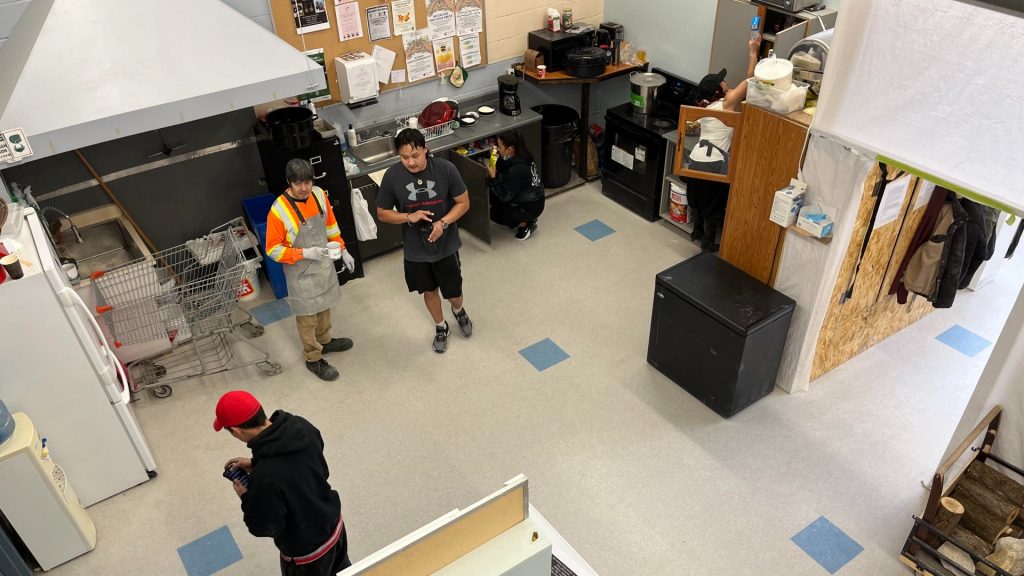

Isaruit’s space includes a sealed, ventilated area for carving, a large dedicated sewing room, and a communal kitchen where visitors can come to cook their own country food, as well as sitting spaces where people can come to share a cup of tea or coffee with others.

David Erkloo, originally from Pond Inlet, Nunavut, is a shop instructor at Isaruit specializing in teaching how to make traditional tools like ulus, knives and harpoon heads.

He said offering individuals a space to connect through cultural activities offers them a gradual opportunity to break out of their shells at their own pace, especially important for those who’ve just moved down to Ottawa or others struggling to adapt to urban life.

“Sometimes they’re shy at first and hardly speak, then slowly they do: ‘How do I use this tool? What should I do next?’ Then they open up and start talking about anything and everything and it’s therapeutic in a way. Then at the end they might even give you a hug. It’s very fulfilling.”

Tristan Webster, originally from Iqaluit, but raised in British Columbia, found out about Isaruit from David Erkloo in January and has been coming to carve since then.

“They have all kinds of stone, all the materials available, people to help you if you need anything,” Webster said. “It’s just a really terrific place.”

Role expanding with population

Beverly Illauq, a founding coordinator of Isaruit, says Inuit qaujimajatuqangit (Inuit knowledge), informs every aspect of Isaruit—from its wide-open communal space flooded with natural light, to its all-Inuit board—and serves as the basis for the center’s success.

“Isaruit is not organized in a pyramid, hierarchical shape,” she said. “In our staff meetings, everyone has equal airtime and everyone chips in. It’s collective governance where you look at each other in the eye and work as one organism.”

The Ottawa Inuit community, the largest in Canada outside of the North, is estimated by several community groups to be between 3,700 and 6,000.

Illauq said Isaruit’s role is constantly growing, and now includes things like arranging intercultural exchanges with other Ottawa groups, giving presentations on Inuit culture, and initiatives like building the Isaruit Inuit artists profiles page.

“It’s taken Inuit a long time to find this place and to trust it,” Illauq said. “Now they know that we’re here and why we’re here and it’s because it’s run descriptively by Inuit and in the Inuit way.”

Financial pressures amidst new policies

But despite the successes of Isaruit, financial challenges emerged following federal government devolution initiatives.

The policies handed funding for Inuit language support and development to political organizations instead of cultural ones, posing problems for organizations like Isaruit, Illauq said.

“There are four recognized Inuit regions in northern Canada, but Inuit in Ottawa are not recognized as an Inuit community in the policies,” she said.

“As of around March 15, 2023, all of the Inuit organizations in Ottawa who depended on the Heritage Canada funding, such as Isaruit, lost between $300,000 and $500,000 from the budget.”

As a result of the changes, Illauq said Isaruit had to manage from August 1, 2023 to Feb 1, 2024 on $56,000.

“Isaruit was maintained because of the good-will of the staff, and even the elders, who were willing to work for as little as $100 a week to keep the shop open because they are committed to the mission of serving their fellow Inuit with a space, that for them, is like an elders home.”

‘Here, it’s honest respect’

July Papatsie says he’s an example of why people remain so committed to Isaruit’s mission— because of how it helped him transform his life.

Papatsie, 63, is an accomplished artist from Pangnirtung, Nunavut, who also previously worked for the federal government, once struggled with drinking, drugs and homelessness in Ottawa and credits coming to Isaruit with helping him turn his life around.

“When I was heavily drinking and consuming marijuana a lot, the only respect I got was when I was sharing alcohol or pot,” he said.

“But here, when I share my knowledge, and the knowledge of how to read a stone for cracks, or how to minimize the cutting so you don’t lose too much of the rock that you’re working with, it gives me a new sense of respect from others. But here, it’s honest respect.”

Now a mentor at Isaruit, Papatsie does everything from helping people carve, or just hanging out to talk. He says he wants other Inuit in Ottawa to know Isaruit is place they’re always welcome.

“When I carve, I calm down, I get grounded,” he said. “I forget my other problems. All I do is concentrate on the piece. And when I teach carving and pass on my knowledge, it gives me a sense of well-being and a sense of self-respect.

“I encourage other people to come here if they are homeless, or if they are not. They can experience the same thing.”

Comments, tips or story ideas? Contact Eilís at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Ottawa Inuit org opens new Food Security Program building, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Sami joik, symphonic music fusion from Finland makes int’l debut in Ottawa, Eye on the Arctic

Greenland: New exhibition features 2000 years of Inuit art from Canada, Alaska, Greenland & Siberia, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Certification marks help both Sami artisans and consumers, says council, Eye on the Arctic

Sweden: Arctic city of Kiruna competing for the European Capital of Culture title, Radio Sweden

United States: How Inuit culture helped unlock power of classical score for Inupiaq violinist, Eye on the Arctic