Ice-Blog: Greenland greening, ocean in turmoil—seeking Arctic climate hope…

After the disappointing outcome of COP28 in Dubai, with February threatening to be the hottest in recorded history – the tenth record-hot month in a row – I have been putting off this ice blog post, hunting for the positive, trying to find signs that things might change for the better in 2024.

For the first time, global warming has exceeded 1.5C across an entire year. With extreme weather causing havoc around the globe while war in Ukraine and the Middle East push the climate emergency off the radar, that is not an easy task.

The Arctic in particular has been the focus of several alarming pieces of research published in the last few weeks.

Arctic Ocean Heatwaves

With monthly global ocean surface temperature at a record high for the 10th consecutive month, and experts baffled over the mechanisms responsible, a study published by the University of Hamburg in the journal Communications Earth & Environment found that marine heat waves in the Arctic as a product of higher anthropogenic greenhouse-gas emissions will become a regular occurrence in the near future. Dr. Armineh Barkhordarian and his team from the University’s Cluster of Excellence CLICCS say their data confirms that conditions in the Arctic have shifted since 2007. “There is less and less of the thicker, several-year-old ice, while the percentage of thin, seasonal ice is consistently increasing.” However, the thin ice is less durable and melts more quickly, allowing incoming solar radiation to warm the water’s surface.

Between 2007 and 2021, the marginal zones of the Arctic Ocean experienced 11 marine heat waves, producing an average temperature rise of 2.2 degrees Celsius above seasonal norm and lasting an average of 37 days. Since 2015, there have been Arctic marine heat waves every year. Officially, a marine heat wave is declared when temperatures at the water’s surface are higher than 95 percent of the values from the past 30 years for at least five consecutive days.

In 2020, the most powerful heat wave to date in the Arctic Ocean continued for 103 days, with peak temperatures that were four degrees Celsius over the long-term average. The probability of such a heat wave occurring without the influence of anthropogenic greenhouse gases is less than 1 percent, according to the calculations by climate statistics expert Barkhordarian and his colleagues. They say this narrows down the number of plausible climate scenarios in the Arctic. Annual marine heat waves will be the norm. The scientists find that heat waves are produced when sea ice melts early and rapidly after the winter. When this happens, considerable heat energy can accumulate in the water by the time maximum solar radiation is reached in July.

“Not just the constant loss of sea ice but also warmer waters can have dramatic negative effects on the Arctic ecosystem,” Barkhordarian warns. Food chains could collapse, fish stocks could be reduced, and overall biodiversity could decline.

Ice island turning green

“Land cover changes across Greenland dominated by a doubling of vegetation in three decades” was the title of a study published by a team of scientists from the University of Leeds in February. Greenland, the world’s biggest island, covered mostly by the northern hemisphere’s largest ice sheet, is turning increasingly green. The experts analysed satellite records and found that over the last three decades, Greenland has lost 28,707 square kilometres or 11,000 square miles of ice. Ice is increasingly giving way to tundra and shrubland. “At the same time, water released from the melting ice is moving sediment and silt, and that eventually forms wetlands and fenlands,” said Jonathan Carrivick, a scientist at the University of Leeds and co-author of the study. The wetlands, in turn, are a source of methane emissions, creating a climate feedback effect. The total area of ice loss represents about 1.6 percent of Greenland’s total ice and glacier cover.

Since the 1970s, the region has been warming at double the global average rate. On Greenland, average annual air temperatures between 2007 and 2012 were 3 degrees C warmer, compared with the 1979 to 2000 average. And the researchers warn that more extreme temperatures are likely in the future.

More of Greenland is seeing vegetation like here in Zackenberg. (Irene Quaile)

The team, which has tracked the changes across Greenland from the 1980s through to the 2010s, say warmer air temperatures are causing the ice to retreat, which in turn is having an impact on the temperature of the land surface, greenhouse gas emissions and the stability of the landscape.

Snow and ice are good reflectors of the sun’s energy hitting the Earth’s surface and this helps to keep the Earth cooler. As the ice retreats, it exposes bedrock which absorbs more solar energy, raising the temperature of the land surface.

Similarly, as ice melts, it increases the quantity of water in lakes. Water absorbs more solar energy than snow and this also increases the temperature of the land surface.

Permafrost – a permanently frozen layer below the Earth’s surface – is being degraded by the warming and in some areas, the scientists warn that this could have an impact on the infrastructure, buildings and communities that exist above it.

Michael Grimes, the lead author of the report, stresses the changes are critical , “particularly for the indigenous populations whose traditional subsistence hunting practices rely on the stability of these delicate ecosystems”.

At the same time, he warns that the loss of ice mass in Greenland is a substantial contributor to global sea level rise, and so of concern to us all.

Greenland losing more ice than previously thought

A study published in January in the journal Nature examining almost 40 years of data revealed that Greenland’s glaciers have lost more ice than previously thought.

Previous assessments of Greenland’s ice loss considered only the losses that were caused by melt and glacier movement, but did not include losses at the edge of the ice sheet resulting from what is known as glacier terminus retreat.

“What we found surprised us,” the authors said in a Nature research briefing about their work, quoted by Eilis Quinn on Eye on the Arctic.

“Our results indicate that, by neglecting calving-front retreat, current consensus estimates of ice-sheet mass balance have underestimated recent mass loss from Greenland by as much as 20 per cent,” the paper’s authors say.

The scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California drew from five publicly available datasets that cumulatively tracked the month-to-month positions of 236,328 glacier edges as detected, either manually or by computer algorithms, in satellite images. They covered the period from 1985 to 2022.

They then used this information to create map representations of the ice sheet for every month in the period. Afterward, they studied the maps to identify patterns in the way the ice sheet expanded or reduced in size.

Although the additional loss of more than 1,000 gigatonnes of ice is not enough to add to sea level rise worldwide, it represents a significant influx of fresh water to the ocean, the experts conclude. Recent studies have suggested that changes in the salinity of the North Atlantic Ocean from melting icebergs could weaken the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, part of the global “conveyor belt” of currents that transport heat and salt around the ocean. This could influence weather patterns worldwide, as well as affect ecosystems, the authors said.

“The Day after Tomorrow”- Hollywood blockbuster not so far fetched?

That ocean circulation is the subject of a widely reported and concerning study recently published in Science Advances. The increasing influx of fresh water from Greenland ice sheet melt is a key factor in changes to AMOC, one of the key climate and ocean forces of the planet. Studies have shown the AMOC to be slowing, but there is much debate over whether or when a complete collapse or shutdown might occur.

The study identifies early warning signs and finds that the “nightmare” scenario of an abrupt shutdown of Atlantic Ocean currents that “could put large parts of Europe in a deep freeze”, as AP’s Seth Borenstein puts it, is looking a bit more likely and closer than before, with a “cliff-like” tipping point looming in the future. The researchers found that the catastrophic development could happen within decades, rather than the centuries previously assumed. That is a very frightening prospect.

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), said it has medium confidence that there will not be a collapse before 2100 and generally downplays disaster scenarios. But study lead author Rene van Westen, a climate scientist and oceanographer at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, several scientists not involved in the research and a study last year say that may not be right.

“We are moving closer (to the collapse), but we we’re not sure how much closer,” Van Westen said. “We are heading towards a tipping point.”

When this global weather calamity may happen is “the million-dollar question, which we unfortunately can’t answer at the moment,” van Westen said. He said it’s likely a century away but still could happen in his lifetime. (He is thirty).

“It also depends on the rate of climate change we are inducing as humanity,” van Westen said.

There we have it.

The Daily Telegraph quoted Professor Jonathan Bamber, director of the Bristol Glaciology Centre, saying the new research was “entirely unrealistic for even the most extreme warming scenario over the next century”. But on the scientific blog RealClimate, ocean scientist Professor Stefan Rahmstorf, head of Earth Systems Analysis at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Research in Germany, describes the study as “a major advance in AMOC stability science.” He describes it as “observational data from the South Atlantic which suggest the AMOC is on tipping course”. The model simulation was “just there to get a better understanding of which early warning signals work and why”, Rahmstorf says.

“The new study adds significantly to the rising concern about an AMOC collapse in the no-too-distant future,” Rahmstorf said in an email to AP. “We will ignore this at our peril.”

University of Exeter climate scientist Tim Lenton, also not part of the research, said the new study makes him more concerned about a collapse. An AMOC collapse would cause so many ripples throughout the world’s climate that are “so abrupt and severe that they would be near impossible to adapt to in some locations,” Lenton said.

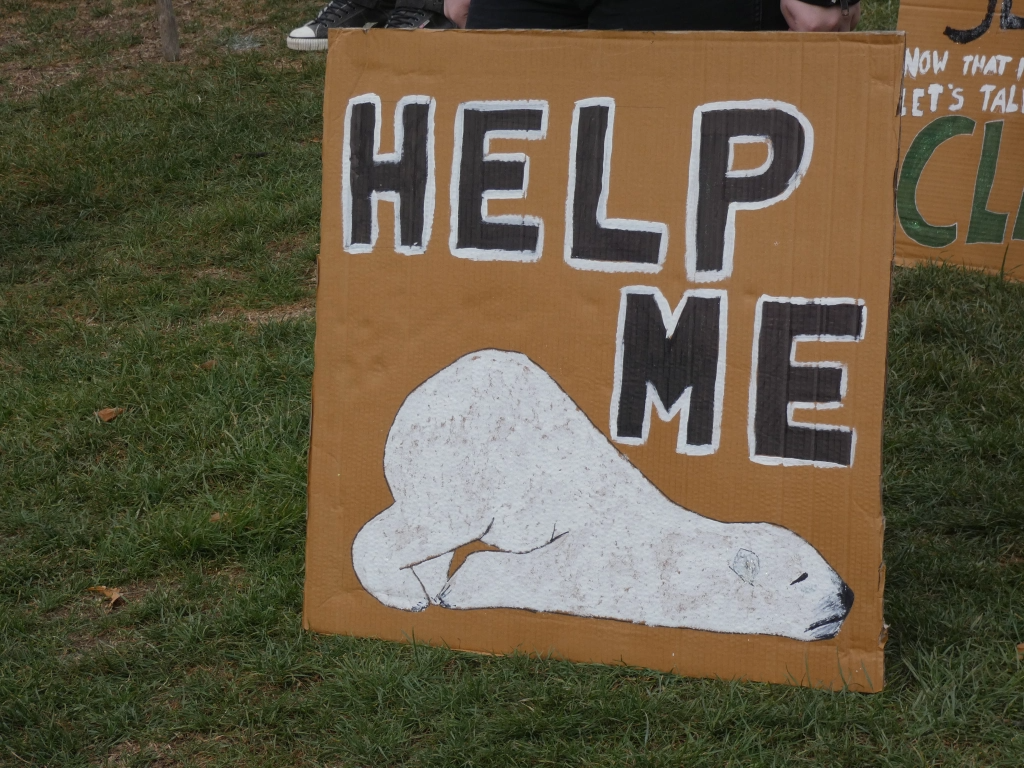

Polar bears back in the headlines

When it comes to communicating the Climate Emergency, there has been a lot of debate in recent years about the effectiveness of polar bear pictures. Some media and conservation groups have moved away from focusing on the undoubtedly photogenic polar bears on the grounds that such images were over-used in the past and also were not suitable to convey the huge threat to humankind as well as the planet as a whole.

I have never seen it quite like that. Polar bears on dwindling ice work for me. We are all in this together. It’s not just about the bears. Climate change is threatening the biodiversity of the planet, of which we are a part. That does not mean I am any less concerned about the millions in low-lying areas, areas far from the poles, already bearing the brunt of weather extremes, droughts and floods, sea level rise and food shortages. The causes are the same. And whether you like it or not, there can be no denying that many people are moved by images of “cute and cuddly” animals where they switch off from pictures of disaster-stricken human misery.

Anyway, the white giants have made it back into the headlines with a new study published in the journal Nature Communications showing that polar bears in Canada’s Hudson Bay risk starvation as climate change lengthens periods without Arctic Sea ice, although they are trying to expand their diets. They rely on the sea ice during colder months to hunt seals, their main source of food.

With the Arctic warming up to four times faster than the rest of the world, the ice-free period in parts of the Arctic is becoming longer, forcing the polar bears to spend more and more time on land.

“Polar bears are creative, they’re ingenious, you know, they will search the landscape for ways to try to survive and find food resources to compensate their energy demands if they’re motivated,” Anthony Pango, a research wildlife biologist with the US Geological Survey and lead author of the study, told AFP.

The new research looks at 20 polar bears in Hudson Bay, trying to find food without sea ice. The scientists used video camera GPS collars to track the polar bears for three-week periods over the course of three years in the western Hudson Bay, where the ice-free period has increased by three weeks from 1979-2015, meaning that in the last decade bears were on land for approximately 130 days.

Ultimately the researchers found that the bears’ efforts to find sustenance on land did not provide them with enough calories to match their normal marine mammal prey. Nineteen out of the 20 polar bears studied lost weight during the period consistent with the amount of weight they would lose during a period of fasting, researchers said. That means that the longer polar bears spend on land, the higher their risk for starvation.

The world’s 25,000 polar bears remaining in the wild are endangered primarily by climate change.

Limiting planet-warming greenhouse gases and keeping global warming under the Paris deal target of 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels would likely preserve polar bear populations, Pango said.

John Whiteman, the chief research scientist at Polar Bears International, who was not involved in the study, commented:

“As ice goes, the polar bears go, and there is no other solution other than stopping ice loss. That is the only solution,” he told AFP.

Any grounds for hope?

So things are not looking good for the Arctic, those who live there, and the rest of the planet, given the global impact of those changes in the High North.

The Arctic is experiencing disproportionately higher temperature increases compared to the rest of the planet, triggering a series of cascading effects. This rapid warming has profound implications for global climate patterns, human populations and wildlife.

All the experts mentioned above are clear about what we have to do to change the situation. Rapid and substantial cuts in greenhouse gas emissions. But what does it take to bring about the changes in our consumption patterns and lifestyles to make a difference?

We have more than enough scientific evidence. Maybe we need to turn to the psychologists to find out how to motivate the behavioural changes. One thing that has given me a little hope is a study by behavioural researchers at the University of Bonn, the Leibniz Institute for Financial Research SAFE in Frankfurt, and the University of Copenhagen. They demonstrate for the first time that a broad majority of the world’s population SUPPORTS climate action and is willing to incur a personal cost to fight climate change.

Now that is something we don’t usually hear!

The findings, published in Nature Climate Change, are based on a globally representative survey conducted in 125 countries, involving approximately 130,000 individuals. According to the study, 69 percent of the world’s population is willing to contribute 1 percent of their personal income to the fight against climate change, with most overwhelmingly backing green policies (86 percent) and demanding bolder leadership (89 percent).That would be a significant contribution to climate action.

It hardly seems surprising that the willingness to fight climate change is significantly higher in countries particularly affected by global warming. In wealthier countries with a high GDP per capita, the willingness is lower compared to other countries. The Daily Mail picks up on the fact that in the UK, just 47.6 per cent of Britons said they’d be willing to contribute. That makes it one of just 11 countries where the majority of people are not willing to pay 1 percent of their income. That list includes the USA and Canada. Perhaps people are just too well off to be willing to make any kind of sacrifice? Or are lulled into a false sense of security by their current prosperity?

On the whole, though, Armin Falk, behavioural economist and professor of economics at the University of Bonn, one of those who conducted the study, sees the results as “tremendously encouraging”.

“The world’s climate is a global public good, and its protection requires the cooperative effort of the world’s population. We establish that a broad majority of the world’s population supports climate action,” Falk said.

“We also document widespread approval of pro-climate social norms in almost all countries,” says SAFE economist Peter Andre. According to the survey results, 86 percent of respondents believe that people in their country should try to fight global warming. “Moreover, there is an almost universal global demand that national governments should do more to fight climate change,” adds Andre.

More people than you think want climate action

Yet in every single country, the researchers found that people underestimate the willingness of other people to fight climate change.The actual proportion of fellow citizens willing to contribute 1 percent of their income to climate action (69 percent) is underestimated by 26 percentage points globally.

“Systematic misperceptions about other people’s willingness to take action against climate change can be an obstacle to the successful fight against climate change. People who systematically underestimate public support for climate action are often less willing to take action themselves,” says Falk.

In other words, we are more likely to make sacrifices or change our behaviour in the interests of the climate when we think our neighbours and others will do the same. That suggests a potentially effective strategy to make progress on the climate front.

“Rather than echoing the concerns of a vocal minority who oppose any form of climate action, we need to effectively communicate that the vast majority of people around the world are willing to act on climate change and expect their national government to act,” the researchers write.

“The current pessimism is discouraging and paralyzing. Our findings suggest that more optimism about climate action can unleash a positive dynamic,” adds Andre.

That is something I am taking to heart here. A large majority of our fellow citizens are actually concerned and willing to make sacrifices. How about that to help combat the Arctic climate blues? This sense of shared perceptions and common purpose could be key in bringing about the political action and economic transition we need to reduce emissions and ensure the healthy survival of our planet and life upon it – including us humans who are making such a mess of it.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Isolated and expensive, the N.W.T.’s Sahtu riding feels squeeze of climate change, CBC News

Finland: Sámi knowledge helps developing climate policies, The Independent Barents Observer

Greenland: Canada and Greenland sign letter of intent on marine conservation area in Arctic, Eye on the Arctic

Russia: Oral histories unlock impact of climate change on nomadic life in Arctic Russia, says study, Eye on the Arctic

United States: Warming North pushing earth into “uncharted territory”: Arctic Report Card, Eye on the Arctic

I have a lot of respect for the work of scientist Dr James Lovelock on his Gaia Theory, from the 1970’s onward. In it he proposes that the world’s systems are self regulating and will ultimately correct for damaging interference, such as a runaway human population explosion dumping ancient fossil carbon back into the atmosphere and environment.There are now 2.5 times as many people on Earth as when I was born in the 1950’s, and fossil fuel use still increases every year, so there can be no long-term climate solutions with 8 billion or more humans.

If AMOC turns off, which now seems likely within one human lifetime, the effects will be to quickly reinstate northern sea ice, and demolish the most polluting human economies in the northern hemisphere, undoubtedly culling much of the excess human population in the process. I therefore see the potential for AMOC collapse as the one positive news stories of recent times, because there is nothing else that is likely to reverse the damage humans seem determined to do to this planet.