Arctic collections behind the scenes—The Canadian Museum of Nature

On any given day, a visit to the Canadian Museum of Nature’s Arctic gallery in Ottawa, Ontario will be filled with a hum of different people and languages, kids marveling at taxidermied polar bears while international tourists marvel at specimens exclusive to the North or at the sheer size of northern sea mammals.

But what many visitors don’t know, is that tucked away in Gatineau, Quebec, approximately 13 km from the bustling exhibits, you’ll find the Canadian Museum of Nature’s Natural Heritage Campus.

This unassuming site serves as the hub for the institution’s scientific initiatives, including numerous collections covering Canada’s plant, animal, and aquatic life, including numerous specimens from the North, some even going back to the 1700s.

Eye on the Arctic recently toured the Gatineau facility to see some of the museum’s northern specimens and the scientific contributions going on behind the scenes.

Preserving nature’s code in deep freeze

The Canadian Museum of Nature is known for its collections—algae,animals, fossils, minerals, and plants—that now number nearly 15 million specimens.

The primarily morphological collection prioritizes the preservation of the size, shape, and structure of animals and plants. Different techniques can be used for specimen preservation, ranging from fixation, such as a fish preserved in formaldehyde or a taxidermied lemming, to dehydration for plants.

This allows scientists to study structure, forms and changes in animals and plants over time, providing a crucial window into the earth’s biodiversity.

However one thing that can’t be preserved this way, is the DNA, and that’s where the National Biodiversity Cryobank of Canada can step in.

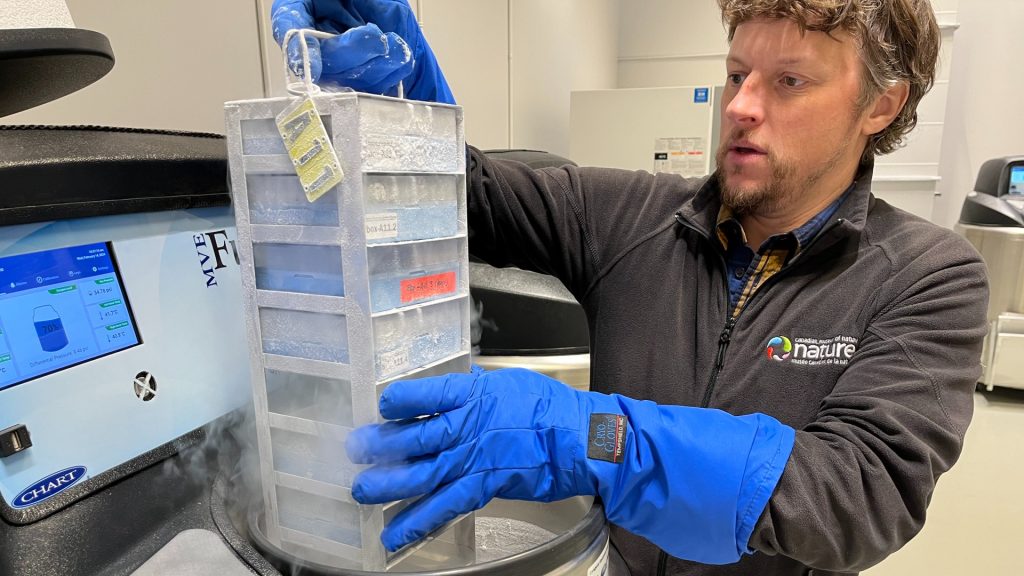

Opened in 2018, this facility is where researchers can donate DNA samples from specimens, allowing for further research to understand evolutionary relationships, identify new species, and preserve genetic information.

“You can kind of think as DNA as book with information about biodiversity, all the information is there, but over time if it’s not preserved properly, it’s kind of like going through a paper shredder,” Roger Bull, the Cryobank’s Head of Operations, said. “The information is still there but it takes more time and effort to extract that information.”

The facility includes six fusion freezers that are cooled with liquid nitrogen. The temperatures in the freezers go to -170 C to preserve the samples.

” At those temperatures, the DNA molecules are effectively locked in time, ensuring minimal degradation,” Bull said.

The cryobank currently holds around 50,000 samples, which is a quarter of its 200,000-sample capacity.

The cryobank was set up both to supporting the museum’s researchers’ collection activities as well as to receive samples from external researchers. The samples can then be checked out by scientists in Canada or internationally.

“We’re spreading the word and inviting people to donate their collections to us, so that we can make sure that they are stored in perpetuity and become available to the biodiversity research community through our loan program,” Bull said.

The unsung heroes of the Arctic ecosystem—lichens and mosses

When people think of the Arctic ecosystem, the first thing that usually comes to mind is things like polar bears or sea ice. But Arctic plant life is rich and varied with lichens and bryophytes—which includes non-vascular plants like mosses—playing key roles in regulating the Arctic ecosystem.

“All you have to do is take a look at one square metre of tundra, and you can find dozens of species in that little space,” Jennifer Doubt, Curator of Botany, said. “All of the plants and animals living in this vast tundra are relying on that tundra mat of bryophytes and lichens. All of their food, all their moisture, everything is regulated by bryophytes and lichens in the tundra.”

Understanding the changes in lichen in the face of climate shifts is increasingly important and is where collections like the museum’s play an important role.

“One of the most important things about detecting changes is to have baseline information about what was there in the past,” Doubt said. “And so a collection like ours that has specimens that were collected 100 years ago, 200 years ago, is a great resource for people who are looking at past changes, and then predicting how things are changing in the future.”

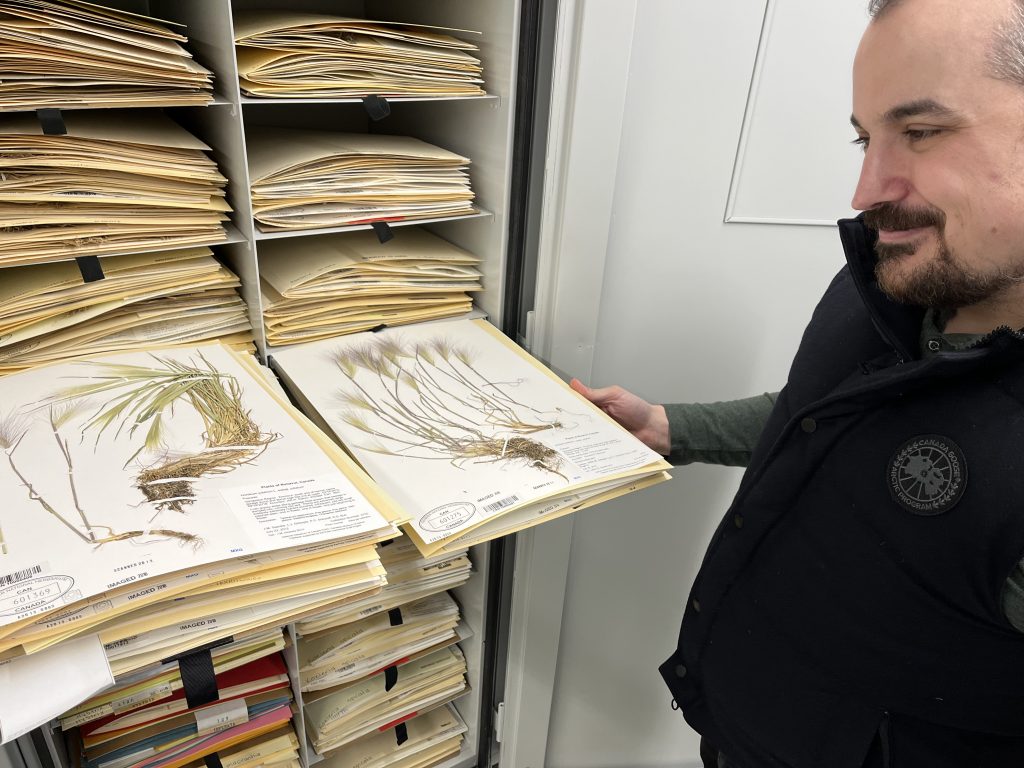

Paul Sokoloff, Senior Research Assistant, Botany, travels to the North regularly to collect samples and says preparation always starts with research on the current botanical specimens.

“It always starts and ends with the herbarium,” he said. “Using the database that we have, we look for any specimens from an area that already exist to get an idea of what’s there, then up north, we’ll spend a couple of weeks out on the land living in field camps and collecting.

“If it’s a vascular plant, we’ll press them in a plant press. And for lichens and the bryophytes, we’ll deposit them in a paper bag and let them air dry. We prepare all the labels with all the information then come back with bundles and bundles and pass it on to Jennifer’s team where they take over.”

The specimens are a rich source for researchers, but Doubt said the collection is utilized by people from various disciplines, including artists and women’s studies students documenting contributions of female botanists to the field.

“It’s a surprisingly surprisingly diverse group of people we welcome whether in person or online,” Doubt said.

Illuminating Arctic fish diversity over time

The museum’s zoology collection has 1.25 million vertebrate specimens that includes birds, mammals, reptiles and the biggest collection of Canadian Arctic fishes in the world.

“We have representatives of definitely more than half and probably getting close to three quarters of the fish that are found in the Canadian Arctic,” Katriina Ilves, Research Scientist, Ichthyology, said.

The extensiveness of the collection makes it a treasure trove for scientists wanting to better understand biodiversity in the North, something that is being added to all the time.

Ilves points to the recent trip to Cambridge Bay, Nunavut where the team was able to record the presence of the Arctic shanny fish for the first time.

“A lot of these fishes that aren’t used for food or commercial purposes are less studied, so we don’t know that it’s a new movement or is new to the region, just that it’s never been documented there before,” she said.

“But every time we go somewhere in the Arctic, we’re very likely to find something new, even if it’s just a new distributional point for a species, or sometimes, it might actually be indicating the migration of species northward, which is a common pattern that we’re seeing now with global warming.”

The museum’s 90,000 Arctic fish specimens give researchers a way to better understand changes to aquatic life over time.

“With changes in water temperatures, species that formally could not tolerate the colder waters of the Arctic are starting to move northward and creep in and that can change the ecology of the region,” Ilves said. “But here we have this historical record going back decades, and for some collections more than a hundred years, where we know what species were found, what species they were found with, and in what approximate numbers.

“This is amazingly useful for lots of reasons, especially in the context of the changing world that we’re seeing now.”

Comments, tips or story ideas? Contact Eilís at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: This stubborn shrub is helping to keep Arctic river banks intact as permafrost thaws, CBC News

Finland: River ice and white hares: Finnish scientists study signs of climate change in nature, Yle News

Greenland: Glowing snailfish full of antifreeze proteins found off coast of Greenland, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Vegetation in Arctic Europe disturbed by mid-autumn thaw, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: Alaska’s fisheries face climate change, costs; fewer youth join trade, The Associated Press