Exploring Norse-Inuit links: How walrus ivory shaped medieval Arctic trade routes

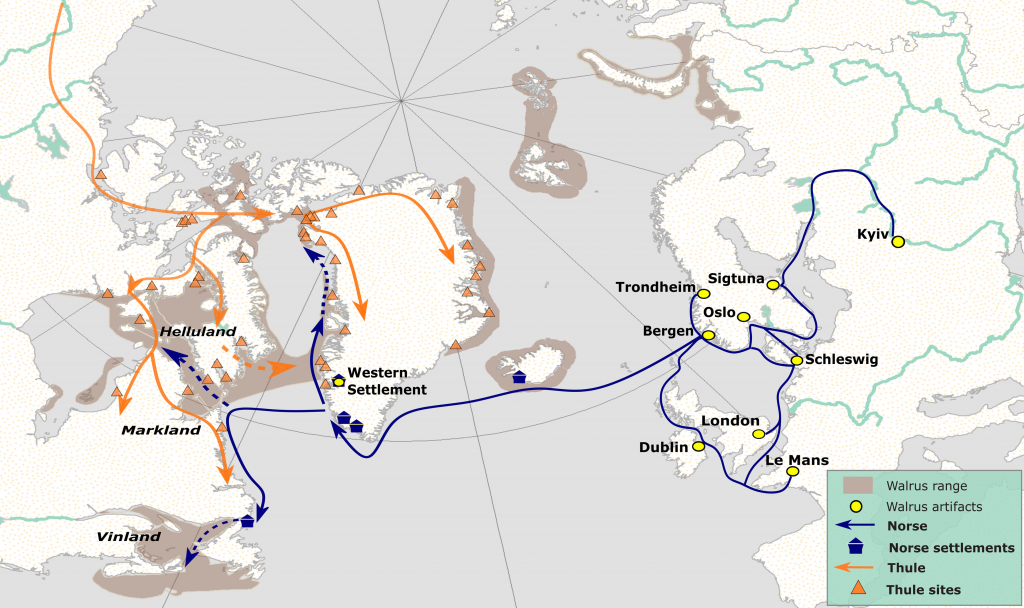

Medieval Norse settlers in Greenland travelled deep into the Arctic, including parts of what is now Canada, to hunt walruses and feed Europe’s booming ivory trade, suggests a recent study.

Using advanced DNA techniques, the paper’s authors traced the origins of walrus ivory artifacts found in European markets back to specific hunting grounds, including those in Greenland and the Canadian Arctic.

“Our results contribute fresh empirical insights to long-running debates about the likely location, timing, and motivations of early interaction between European Norse and Indigenous North American communities in the High Arctic,” the international research team said in the study.

“The results confirm that elite consumption patterns in Europe fueled an insatiable demand for walrus ivory, and that provisioning these markets emerged as a major driving force that substantially shaped the trajectory of Greenland Norse interactions with Arctic Indigenous peoples.”

Circumpolar “globalization” — medieval style

Walrus ivory was highly valued in medieval Europe, and was used to make luxury items.

It’s long been known that the Norse were key players in the European walrus ivory market of the time.

But the recent research published in the journal Science Advances, suggests that as demand grew, the Norse had to travel deeper into the Arctic to find more walruses, which put them in increasing contact with Inuit communities, who were already skilled and knowledgeable about about hunting the animals in challenging and remote regions.

These interactions may have played a significant role in the transfer of hunting techniques and knowledge, the paper said.

“Such voyages would have increased the likelihood of encounters, especially if other Arctic Indigenous groups were hunting similar resources in the same areas, perhaps encouraging a shift from direct Norse acquisition to some form of exchange relations,” the researchers said.

“If more formalized trading relations did somehow emerge, they would represent some of the earliest steps toward circumpolar “globalization,” a process that would eventually define later historical periods, including expansive culture contacts, intensive trade networks, and the market-driven exploitation of the Arctic’s natural resources by distant polities and urban consumption centers.”

Feeding a luxury demand

The study’s findings also highlight just how skilled the Norse were as sailors and boat craftsmen given that they were able to undertake such long-range trips in the world’s harshest maritime environment in the Arctic.

These journeys didn’t just last weeks, but they would also have to return with walrus tusks to trade across Europe.

“The Greenland Norse had the greatest incentive to voyage deep into the High Arctic in search of ivory; they also had the seafaring capabilities, and emergent socio-political dynamics may have led elites in Greenland and Norway to sponsor such longer-range harvesting expeditions,” the paper said.

Charting the story of Arctic resource exploitation

The findings are just the beginning of cracking the patterns and consequences of Arctic resource development, the paper said.

“The methods used in this study highlight enormous potentials for a more comprehensive and truly circumpolar sourcing program to reconstruct the causes, conditions, and deeper ecological consequences of Arctic resource exploitation across different cultural and historical contexts,” they said.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: What Arctic ice can tell us about plagues, climate and conflict in the Middle Ages, CBC News

Greenland: Greenland ice cores reveal historic climate clues, says study, Eye on the Arctic